Ho Dyak put her down and turned to face the drog.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Fog of the Forgotten, by Basil Wells

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you

will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before

using this ebook.

Title: Fog of the Forgotten

Author: Basil Wells

Release Date: November 20, 2020 [EBook #63817]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

Produced by: Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FOG OF THE FORGOTTEN ***

The fog of their world matched the fog in

their minds. Rebelling against science, they

smashed it, dragged their people down into

the ancient mists. But Ho Dyak wanted light.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Winter 1946.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The fog sea thinned before Ho Dyak, and he could see the dank rocks of the cliffs he scaled a scant twenty feet beneath his feet. The network of blue-veined pale vines that he climbed thinned even as the air itself thinned. Far below him in the lowlands the mat of agan vines was three hundred feet in depth in many places.

Higher and higher climbed Ho Dyak, his long pale face, with its full red lips and great thick-lidded purple eyes, drawn with pain. For the air of the uplands was chill. As the fog thinned, so too dropped the temperature.

Ho Dyak gripped tighter the pouch of flayed drogskin, in which five of the forbidden foot-long cylinders of metal skins nestled, as he paused for a moment to rest. It was because of them, the forbidden scrolls stored in a musty forgotten chamber of the Upper Shrine of Lalal, the One God of Arba, that Ho Dyak was now climbing into the frigid death of the cloudless uplands.

The ivory-skinned body of the man was swathed in layer upon layer of quilted and padded garments of leather and fabric. His two feet, with their webbed outstretched toes, and his short stubby middle limbs, strong-fingered webbed hands at their ends, were encased in sturdy mitten-like moccasins. Only his long upper hands were encased in stout leather gloves with four divisions—one for the thumb and the other three for his four-jointed fingers.

Over his grotesquely swollen bulk, for which his myriad garments were responsible, Ho Dyak's sword belt and the filled sheath of javelin-like darts were belted. To his crossed belts also were attached his broad-bladed machete-like knife and the throwing stick for his dwarfish spears.

No longer did he fear pursuit. The fighting priests, the dark-robed orsts of Lalal, had brought with them none of the warm garments Ho Dyak wore. Their shouts and sacred battle cries had died away on the slopes a mile or more beneath where he now perched. For the moment he was safe from their vengeance.

"I will see what lies above the fog sea," said Ho Dyak to the unresponsive ladder-like network of agan he climbed. "Perhaps I can, for a few short hours, see the vast plateaus that once my people ruled."

The agan made no answer, as Ho Dyak had expected it would not, but he bent his gaze more closely upon its smooth stems. A greenish tinge lay upon them, a tinge that in the lowlands only the rocks or tarnished metals bore. The man's heart beat faster despite the chilling cold. He was approaching an unknown zone of life!

The fog sea split apart abruptly. His broad shoulders and then his thickly padded middle came above the last remnants of the mist. And he sensed a warmth that came from above—not a pleasant warmth, but a strangely stinging heat. He turned his hooded eyes skyward and pain filled his brain at the glaring redness of the lights that blazed there. Three suns, one huge primary and its offspring, that hung in the cloud-banked blue heavens overhead.

Darkness dwindled into grayness and he could see. He was looking out across a level rolling expanse of fleecy nothingness. A soft sea of foggy mystery from which vagrant hills of vapor drifted upward lightly and settled back again. Down beneath that impenetrable damp blanket, he knew, lay the pleasant stone buildings and palaces of his people, and further away out there rolled the gloomy steaming sea of Thol where men fished and hunted for the mighty aquatic monsters of the deeps.

It was as though his homeland had never been, and he was a castaway here on this sun-drenched vine-covered slope with the blood chilling in his muscular squat body. He shivered.

He looked upward and his heart hammered new warmth into his muscles as he saw that the rim of the mighty wall he ascended was but a score of feet above. He swung himself upward swiftly.

Then he was standing upon a level expanse of grassy land beside a slow-flowing brook. The stream was clogged with aquatic lush vegetation, and further up along it he saw moving shapes, lizard-like creatures and four-legged graceful animals that were covered with a dusty golden fur. Beyond was a jungle of vine-linked growth, and far beyond that a vast escarpment climbed, step upon step, upward to the white-helmeted peaks of a mountain range.

It was at this moment that Ho Dyak became aware of the ragged roaring sound from overhead. He squinted his eyes and was careful not to look into the terrible flare of light that was the suns. The sound increased. After a moment he saw a dark speck low down to the western horizon, a speck that grew into a long stub-winged shape with vapor flaring like smoke from its rear.

At first Ho Dyak thought that some living monstrous thing was diving upon him, and then he saw the fixed rigidity of the boatlike elongated craft. This was a man-made thing, a ship that rode noisily through the air even as the great canoes of the fisherfolk sailed upon the hot waves of mighty Thol.

It was thus that the ancestors of his race had ridden in the long-dead ages before the fog seas shrank downward from the mountains and plateaus. This was one of the machines that his embittered race had destroyed after cataclysmic disaster swept their world. He had thought that only in these precious stolen scrolls was there any record of that mighty civilization; yet here before his eyes a mighty thing of metal dropped swiftly.

Then the winged thing seemed to explode and crumple as it nosed into the green expanse of tangled grasses near him. Flames licked out from the rear of the craft!

Three days had passed there upon the plateau shelf above the fog sea. And Ho Dyak had not returned to the welcome warmth of the lowlands of Arba. Instead, he had found a great spring of boiling water in the rocky valley not far from the crashed ship of the sky, and about this he had built a sturdy dome of clay-plastered stones. Within this comfortably damp and well-heated den Ho Dyak sprawled and talked through the slitted doorway that was closed with triple hides of giant upland lizards.

"I do not understand," said the lanky sandy-haired man who sat, sweating, outside the steaming mud-daubed mound, "why your people, with their marvelous control of telepathy and their one-time control over all this world, are content to live in savagery along the narrow strip of beach they now possess."

Ho Dyak did not move his lips as he answered. Unlike the Earthman from the Lo, he did not need to speak aloud to transmit his thoughts. His hasty schooling of the two men and the girl he had rescued from the battered Lo had been designed to afford immediate communication. Later he would impress upon their brains the process of speechless transmission.

"Inventions, mechanical knowledge, brought about the downfall of Arba, Glade Nelson. Lest any further destructive device do away with our last zone of liveable atmosphere all mechanical knowledge and experimentation is forbidden."

The Earthman snorted. "I know that, Hodiak," he said, using his own word for the squat ivory-skinned man, "but with pressure cities, transparent domes you know, and heated suits like the space suit we gave you, there's no reason why your ancient lands should remain abandoned."

"I agree with you, Earthman. Some of the wisest men of Arba have felt the same. But the priests of Lalal have branded them, branded them with blindness, and driven them out into the agan jungles. They are content with the barbaric simplicity of the lowlands."

"Perhaps," said Glade Nelson, "now that you have escaped with your life and your vision you can help your people in spite of themselves."

Ho Dyak shook his big square head. The broad curly tendrils that sprouted yellowly from his skull half-covered the delicate sharp tips of his upthrust thin ears.

"The power of Lalal over the common people is no light thing."

The thoughts of the Earthman were confused for a moment and then Ho Dyak heard, through the ears of Nelson, the frantic screams of the Earthwoman, the dark-haired sister of Nelson's employer, hairy, stocky Albert Gosden.

Nelson snatched his high-powered rifle and raced away toward the sound. Ho Dyak sprang to his feet as well and slipped swiftly into the space suit that Nelson had provided him. He set the heat controls for a comfortable 200 degrees and pushed aside the hide curtains.

He went racing after the Earthman. Although unhampered by the cumbersome space suit Ho Dyak wore and fleet of foot, Nelson saw the ivory man go racing by him and he marveled at the strength and vitality of the squat Arban. Then they were at the stream, beside a swampy lake, dotted here and there with tree islets and banks of reeds, searching for the girl.

They saw her flailing away at a swarm of scaly black lizard things, young seven and eight foot-long drogs, with a leafy branch. She was safe enough from them as she sat in the crotch of a moss-hung jungle giant at the lake's green-scummed rim. But Ho Dyak saw the ripples that were converging on the girl from other portions of the pool, and he reached down to the weapons belted now about his dull-sheened space suit.

"Albert's dead!" Marta Gosden sobbed, thwacking away. There was a bloody broken thing, or rather, things, that some of the young drogs quarreled over in the thick muddy shallows.

Ho Dyak was busy now with his copper-tipped javelins. He was killing as swiftly as his throwing stick could contact the sturdy butts of the javelins.

"Kill them," he flashed at Nelson, "for the grown monsters come."

But the lanky man with only two arms did not heed his order. In the excitement of the moment Nelson had reverted to the use of his ears—his mental receptive powers were as yet too untrained. Ho Dyak fought alone while Glade Nelson shouted to the girl to climb down a drooping limb toward him.

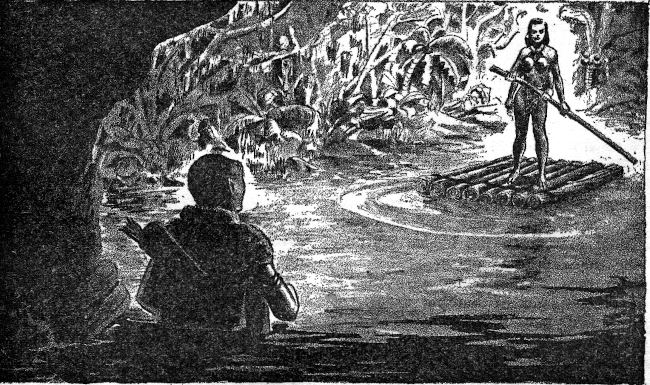

Ho Dyak drove the crawling lizard-beasts back until he stood beneath the tree. He held up his two upper arms, and the girl dropped her leafy useless club before she slid down the loose rough bark of the trunk. Then Ho Dyak turned and raced with her in his arms away from the lake.

Nelson roared with sudden fear. Almost upon Ho Dyak's heels a huge mouth gaped suddenly from the murky water and then a scaly six-legged monster came charging up over the low marshy bank. Behind the first drog came another, and then another. All of them were over twenty feet in length and their pace was not slow. They were overhauling the burdened ivory man.

Ho Dyak put her down and turned to face the drog.

Ho Dyak put the girl down. He gave her a push in the direction of the wrecked ship and with the same motion turned to face the drog's gaping maw. His stout double-edged sword was in his hand. He could feel its welcome pressure through the insulated layers of siladur that sealed out the chill air of the plateau.

His sword flicked up toward the eye of the huge dragon. He pressed the button that released the needle-like extension from the weapon's tip, and his prolonged weapon ripped through the huge reddish eyeball. The monster roared with rage, and whistling with its blasting breath, swung its head. Again the sword flashed and the blinded monster dashed itself against a huge smooth-boled tree. Its legs crumpled for a moment and then it was up ripping ferociously with great nails and rending jaws at the unresisting wood.

By now Nelson had taken a hand. His rocket projectiles were shattering the armor-plated drogs. They were down upon the swampy turf, their mighty bulks crimsoned and torn, and yet they hissed and growled while their dead limbs shredded the dank black muck.

The Earthman turned his weapon upon the unseeing lizard thing and blew its head from its ugly scaly neck. Even then the legs continued to strip bark from the great tree, nor did the great body collapse for several long minutes.

Ho Dyak cleaned his sword-tip and pressed it back upon the spring at its base. Then he went to Nelson and the girl. She had come back when she saw the drogs were down. Nelson was holding the girl in his arms, talking softly to her. He could see in their unguarded minds that they loved one another.

So it was that he turned abruptly away and went back to his comfortable steam-heated igloo of stones. Memories of Mian Ith, she of the rioting pinkish-brown tendrils and the full-breasted slim young body, came to him. Memory of the Earthman's words came to him and his full lips smiled. Yes, he could rebel and lead others.

"Tomorrow," he told himself, "I will go again to the Place of Lalal. There I will find others of the precious scrolls of the ancients. And when I return I will bring with me Mian Ith."

With the knowledge of the Earthman coupled with his own he might indeed restore to his people the empire they had lost when the fog seas shrank away....

Glade Nelson, the Earthman, walked as far as the rim of the lower plateau with Ho Dyak. And, before he swung down into the foggy lake that hid the lowlands and the sea of Thol, he told the Earthman that he might not return.

"If I do not come back," he said, "there is a possibility that you can return to Earth."

Nelson laughed half-heartedly. "Not in the Lo," he said.

"Naturally," Ho Dyak flashed back, "but your helicopter, that you planned to use for exploration on that other planet—"

"Mars," supplied Nelson. "Gosden financed the trip and purchased the ship for me. I'd had experience with submarines and aircraft during the Second War, and Gosden knew me then. His sister stowed away aboard. We were several thousand miles out into space when we discovered her. We turned back to Earth then; our supplies were insufficient."

Ho Dyak smiled. "When was it," he wanted to know, "that you realized something was so terribly wrong—that this was not your home planet?"

"Almost as soon as we had sighted your world of Thrane," said Nelson. "Then we saw the three suns and the two extra planets of your system." He lighted one of his last cigarettes. "Just how did we get here?"

"Probably hit a space-time-material eddy. Our scientists created an artificial eddy, a sort of gateway you might say, between parallel worlds. That's how we lost our dense protective atmospheric envelope. The vibrational gateways, in the course of many years' usage, became permanent. Our ancestors no longer could seal them shut by cutting off the power.

"And so our precious atmosphere drained off into a dozen parallel dimensional worlds. Fortunately the gateways were on the upper plateaus and so a thin envelope of denser air remains. But one of those doors leads through to Earth! Maybe several of them."

Nelson gripped Ho Dyak's bulky shoulder.

"You mean," he gasped, "this is really Earth? Only changed?"

Ho Dyak agreed. "Something like water and sand," he explained, "when they're mixed together. They're distinct but occupy the same space." He turned toward the sea of fog and stepped down into it.

He slipped through the sheltering upper layer of agan vines, their huge disc-shaped leaves of blue-veined yellow as a protective screen about him. Here, three hundred feet above the mucky soil, the thick rubbery coils were not matted together into a solid wall as they were much lower.

He was soon approaching the seacoast city of Gorda, capital and chief city of the priest-ruled nation of Arba. He saw where the floor of writhing pale vegetable stems dropped away abruptly to the mile-wide clearing that the heavy blades of convicted criminals kept cleared away. The shouts of the men, as they hung back on their ropes and hewed at the thick fleshy wall of growth, came faintly to his ears from the fog-shroud off to his left.

The sound of the booming surf came now from the right. He could not see further away than fifteen feet, although his heavy-lidded purple eyes were sharper than the majority of his people, but by the muffled sounds of the city below and the steady throb of the surf's drumbeat, he knew that he was nearing the forgotten twin spikes of a ruined tower. Directly opposite this tower the Place of Lalal heaped its thirty levels, terrace upon terrace, into the eternal thick mistiness of the fog sea.

Then he saw the tips of the tower, two man-made juts of metal ten feet apart and covered with great orange and golden knobs of wrinkled warty fungi. The round holes of sliran tunnels gaped beside the vine-buried dome of the ruined tower—the many-legged blue-scaled snaky lengths of those hideous monsters had kept open a rounded tube something over three feet in diameter.

Ho Dyak had been here before. He drew his sword and lowered himself into the steep slanting hole. As he descended he heard from above the increasingly louder voices of men—some of the workers and their guards were passing. He had entered the sliran burrow none too soon. And now, if he did not encounter a sliran in the vine-walled tube, he would shortly be inside the helmet dome of one-time silvery metal that capped the deserted tower.

A moment later he stepped from the tunnel into the moist thick heat of the broken dome. The broad phosphorescent band of light that was built into the walls of all Arban architecture, waist-high, was dimmed by the slime of ages. But he could see. The dome's interior was not occupied by any of the huge stubby-legged snakes. The slirans spent most of their lives in the muddy pools and root caverns at ground level.

He turned down the ramp that wound into the depths. A forgotten stone-walled passage led under the city walls into the heart of the massive stone pile that was the Place of Lalal. And there, in the pleasant upper-level quarters of the One Orst, the high priest of Lalal, lived the daughter of the One Orst, Mian Ith!

From his leather jerkin and his weapons, some time later, Ho Dyak wiped the slime and encrusted mud. He was hidden in a deserted apartment upon the fourteenth level, the same level that housed the children and mates of the One Orst. Thus far had his dark robe, the garment of a fighting priest who now lay trussed-up with his own harness on the second level, brought him.

Suddenly he crouched behind a massive chest of hammered silver. The apartment's oval stone door-slab was swinging inward! Ho Dyak's sword cleared the leather of his sheath silently. He recognized the voice of the woman who entered the room—Mian Ith! And behind her came a man, a blue-robed priest, one of the seekers after wisdom pledged to the celibate life of a thinker. He wondered why the woman he adored came stealthily to this musty, empty place with this dreamy-eyed seer of the mysteries of Lalal.

"My darling!" cried Mian Ith, her arms going about the slight body of the thinker. "It is so long since we were together!"

"I feared," answered the seeker, his soft high-pitched voice more feminine than Mian Ith's, "that Ho Dyak would persuade your father that you should be his mate. He, like you, wore the red robes of the priestly rulers."

Mian Ith laughed. "The great muscled fool," she sneered. "He thought that I loved him. He told me of his studies in the forbidden books of the Ancients. Iiiy! but did he reveal his twisted unbelieving soul to me! It was a little matter to lay a trap for him—to rid myself of him forever."

Ho Dyak felt his lips curl back from his teeth with scorn and hatred. This, this—woman! Say, rather, this female sliran. She had betrayed him to the priests of Lalal that she might be free to continue her forbidden trysts with this puny seeker! It was true. He could read the woman's unshielded mind now. He had never attempted to do so heretofore.

Two slashes of his keen-edged bronze sword and he would be avenged. And yet Ho Dyak shook his head even as the thought came to him. He was well rid of the false-tongued Mian Ith and the dreamy-eyed seeker he despised. Better had Mian Ith chosen a stalwart black-robed warrior or yellow-robed toiler for her lover.

The man and the woman moved into the other room, their four arms interlocked and their soft head tendrils mingled in that half-embrace. And Ho Dyak slipped from the outer door into the corridor beyond. A half-ruined ramp within the walls, a ramp sealed off ages past and revealed to the boy, Ho Dyak, by a dislodged block of masonry, opened off the ramp a level above. In this way had Ho Dyak climbed in the bygone years to the Upper Shrine of Lalal and taken from the thousands of inscribed metal scrolls those he wished to study.

He would go to the Upper Shrine, fill his pouch with other slim metal skin records of the past, and take as well certain small mysterious objects sealed in crystalline spheres. The Earthman might know their purpose.

And so Ho Dyak ascended the ramp and squeezed through the shadowed opening so familiar to him.

Later, Ho Dyak turned for a last look about the Upper Shrine. He saw crystal-walled cases and unrusting metal devices of the Ancients. Here was static knowledge and machinery that might make Arba the mightiest nation upon the shores of the Sea of Thol. He touched lightly the pouch where nine more of the precious metal scrolls nested. Perhaps after all these centuries the wisdom of the forgotten ages would come to life beneath his four hands' clumsy touch.

It was then that the javelins came from the grayness of the Shrine's further corners.

The One Orst had laid a trap here for Ho Dyak, that profaner of the sacred place, should he ever return!

One javelin pierced his side and another passed completely through the upper muscles of his left middle arm. A third keen-tipped miniature spear struck the handle of his sword and its copper point blunted harmlessly.

From the gray twilight that was all the day men knew beneath the fog sea, there poured a dozen black-robed fighting men. Swords they carried, some of them two and three, and many of them bore the barbed nooses of woven droghide with which they bound prisoners before they were driven, blinded, from Gorda.

Ho Dyak rushed through the panel of stone into the ancient sealed rampway. He paused long enough here to tear the javelin from his side, and was relieved to find that it had ploughed shallowly across his ribs. Then he raced down the dimly lighted narrow way.

This time he did not attempt to use the opening on the fifteenth level. The corridors of the Place of Lalal would be swarming with black-robed warrior-priests and poorly armed yellow-robed toilers. Instead he raced on down the ramp into the dank stench of the lower levels. For the unused ramp led into the same great underground storage cave that he had entered from the rocky tunnel beneath the city walls.

Bricked-up and partially sealed was its end, and for this reason he had not ascended that way. Signs of his passing must have shown in a litter of chipped cement and displaced yellowish slime had he done so. But now he could shove the wall outward and race toward freedom. What matter, now, if they found a gaping hole in an apparently solid supporting pillar of masonry?

He put his eye to the broken wall as he reached the great basement cave in this part of the underground citadel beneath the Place. Apparently no guards had been posted here as yet. He lunged against the wall and it clattered down. Then he darted across the slippery muck and sprouting toadstool growth to the hidden entrance to the tunnel leading outside.

Even then he heard the rasp of the scaly black plates of hunting drogs, the domesticated long-limbed smaller lizards that the warriors of Arba use in hunting upon the agan jungle's upper terrace for the bat-winged wild lizards and white-fleshed, tender, legless serpents so prized on Arban tables. The black-robed ones had turned their swift drogs upon his trail! His only safety lay in flight.

Almost had he reached the abandoned tower when the hunting drogs were upon him. Even as they reached his heels Ho Dyak cast a despairing glance upward—and saw one of the ancient ventilating shafts that supplied air to this buried way.

He sprang upward and his fingers closed upon a tough agan root. A moment later all four of his hands were gripping other roots and he was climbing carefully up through a rounded shaft.

Below him the hunting drogs leaped high into the air and fell back again, whistling, growling and screaming in their saurian stupid way. Twenty feet he had climbed before a solid mat of agan blocked further upward progress. Ho Dyak clung to the huge hairy white roots and peered about him.

Meanwhile the Place's warriors came swiftly up with their six-limbed lizard beasts. A cry of triumph came up to Ho Dyak.

"Come down, Ho Dyak!" one of them shouted, "and we will not permit the drogs to destroy you."

Ho Dyak laughed shortly. "It is you who will destroy me," he said, "and not the drogs. I prefer the drogs."

"Surrender, Ho Dyak," cried the man menacingly, "at once, and the One Orst may but take from you your eyes. Delay, and his tame drogs will eat your limbs, one by one, as you yet live."

"I prefer a javelin," mocked Ho Dyak. "The death is clean and merciful."

"Then take it!" shouted the man, drawing back his throwing stick.

But even as a hail of javelins hummed upward Ho Dyak was in motion. He had swung on his shaggy ladder of roots into a ragged crevice in the side of the shaft. And so the javelins buried themselves only in the rubbery coils of agan. A howl of rage rolled up through the old ventilating shaft.

Ho Dyak crawled further into the narrow crevice. At every instant he expected to find that the probing roots or stems of the fleshy agan had closed this last hope of escape, but as time passed and the way widened he began to hope. Other tunnels branched off from time to time and he crawled through tepid pools of foul water in which he sensed the wriggling of hideous alien things with scaly-finned limbs and tails. The blackness was total. He groped onward.

And then he fell forward into a blackness that was not total and found himself squatting in the shallow muck of a sullen underground river. Or perhaps that lightless roof overhead was but the matted stems and roots of the sunless vines of the fog seas. He saw a faint luminous glow that came from the river. Thousands of tiny light-producing aquatic plant-animals swarmed in the depths.

He saw a raft of tied buoyant agan stems, huge two-foot sections ten and eleven feet long, and poling it along with a tough spear of hide-bound bone, was a woman in a scant, ragged tunic. At the same instant she saw him.

"In Lalal's name," she demanded, "why do you sit in the water so? Are not there few enough warriors in the two caves of the Outcasts without offering yourself thus freely to the water slirans?"

"In Lalal's name," she demanded, "why do you sit in the water so?"

Ho Dyak realized that this was one of the blinded Outcasts, turned out to die in the jungles because they dared question the rule of the One Orst and his priestly underlings.

"I am Ho Dyak," he said, "who is hunted by the black-robed ones, the orsts."

"We have heard of you, Ho Dyak," the blind girl said, "and we welcome you to the poor sanctuary of our caves." She poled the raft nearer. "I am Sarn Vod, daughter of Dra Vod."

"Dra Vod is your father!" cried Ho Dyak. "I have heard of him. He built a machine powered by the sap of pressed agan for his boat!"

"Aye," agreed the girl, "and his reward was blindness. Of the three hundred Outcasts in our rocky caves a hundred are sightless."

"You can see!" Ho Dyak burst out. He was looking into the beautiful slim face of the girl. She was more beautiful than Mian Ith had ever been. From that moment Ho Dyak forgot the faithless One Orst's daughter....

"Of course," agreed the girl, laughing. "I was born after my father was taken into the hidden village of the Outcasts."

They sat close together, then, in the raft, and Ho Dyak opened his mind to the mind of the girl. She in turn opened her mind to him. It was not long that they sat thus but when Sarn Vod took up the pole of bone again they had found that they loved one another.

Never before had Ho Dyak allowed another to probe into the remoter recesses of his brain. But he knew that she could be trusted. Her childlike acceptance of him even before he opened his thoughts to her convinced him of that.

"I will go with you to the camp of the Earthman," she told Ho Dyak softly, as they neared the upreared hillock of soft gray rock from which their two cave homes had been laboriously scraped.

"It is good," agreed Ho Dyak, "and later, when we have found a secure place, I will come back for your people. The Outcasts will be the first to share with us the wisdom of the Ancients."

Sarn Vod flashed him a quick mental caress as the raft grounded in the shelter of an overhanging ledge. He stepped to take her in his arms, and halted as a giant of a man groped toward them. Where his eyes had been there were now but empty sockets.

"My father," said the girl, "Dra Vod!"

"And my father as well," said Ho Dyak, leaping to the blind man's side, and his two middle arms locked with the elbows of Dra Vod's short middle arms.

Dra Vod's own powerful webbed fingers gripped Ho Dyak's elbows in return as their minds interlocked in greeting for a brief moment.

So it was that two days later Ho Dyak and his mate, Sarn, climbed the chill slopes above the lowlands and came to the highlands. With them came two of the Outcasts, young hunters who wished to see the world above the fog sea.

Ho Dyak wore the space suit that he had cached far below in a rocky cliff's creviced wall, and Sarn and the two Outcasts wore as many and more garments than Ho Dyak had worn long days before.

As they came through the last shreds of the watery vapor that flooded the bowl of the Sea of Thol, one of the young Outcast warriors was in the lead. Suddenly he uttered a short, choked cry and fell, toppling back into the mist. And the rocks around them rattled with copper-tipped javelins.

"Quick!" shouted Ho Dyak. "It is the black-robed ones, the priests! They have been lying in wait for us!"

Back into the welcome protection of the fog sea the Outcasts plunged, but now there were only three of them. For one thing was Ho Dyak grateful: the thinning network of agan afforded no safe footing for the hunting drogs.

"We die?" questioned Sarn quietly, and Ho Dyak laughed back at her. They were resting for a moment, listening.

"Not so long as my sword arms last," he said, "and of arms I have four."

"But they will follow us along the rim," objected Sarn. "When we climb upward again they will see us."

"They are cold and hungry," Ho Dyak told her, "and there are none too many of them. If we can reach the plateau safely we can fight them off, until we reach the rocket ship of the Earthman."

"We will be safe with the rocket rifle of Nelson to protect us," agreed Sarn.

Ho Dyak started along the thick stalks of agan again, his arms gripping the interlacing of rubbery greenish stems on his right. And behind him came Sarn and the young Outcast.

By nightfall they had moved a matter of two miles further along the left wall of the barrier cliffs. The lone moon of Thrane had not as yet lifted above the horizon and so they climbed silently upward into an almost complete darkness. Out of the fog sea they made their way, and safely into the dense jungle growth spreading at this point.

Sarn was chilled to the bone, and the young warrior's thick lips were blue with cold. The temperature of the lower plateau had dropped to almost a hundred degrees with the coming of dusk, ninety degrees below that of the lowlands. And so Ho Dyak followed a small stream, warmer than the usual upland streams, up to a rocky bluff where steaming water rolled white vapor into the growing moonlight of the jungle clearing. By some good fortune the hot spring gushed up in the heart of a small cavern and the two Outcasts were not forced to lie in the almost-boiling water.

With morning they marched eastward to the jungle meadow where the spaceship's shattered bulk lay. The spaceship was empty. Ho Dyak saw that the helicopter was gone from the cargo hold, and with it many supplies. Nelson and the girl had thought he was not returning and gone in search of the ancient gateway that might pierce through to Earth!

Ho Dyak turned his eyes toward the mud-daubed hut of stones he had abandoned. His eyes widened at the sight of steam rising from its dome. Could they be—? No, it was impossible. Shattered though it was, the spaceship afforded better protection for Nelson and Marta than the igloo. Then who—?

Immediately, Ho Dyak knew the answer. The black-robed orsts had taken over the igloo! And they were not yet aware of the presence of the Outcasts.

He returned to the hidden Outcasts, his mate and the young warrior, but with him he carried a rocket rifle that Nelson had thoughtfully left behind.

"Come," he told the warrior, "we will drive the black-robed ones from our hut. With the Earthman's gun they will be helpless before us."

They marched side by side, two warriors from the fog sea, toward the rocky dome from which the plumes of white steam jetted. At last the priests saw them and came pouring from their warm shelter.

"Go back to the Place of Lalal," ordered Ho Dyak.

The black-robed, thick-padded bodies of the seven priestly fighting men shook with laughter. These two outcasts ordered them to retreat! They plunged ahead.

The rocket gun whirred and an explosion ripped two of the priest-warriors into tatters. Ho Dyak reloaded and fired, and a third warrior dropped. And then the tiny battery that fired the rocket shell went dead! The third rocket shell did not blast into the attacking men.

Ho Dyak flung down the useless weapon and drew his sword. Javelins could not pierce his space suit, only a sword could crush through to his body. His other hand was busy with his throwing stick and javelins, and he cursed the two limbs of the Earthmen that prevented his middle pair of arms from being used.

Four of the enemy faced the two of them at the last, and their weapons clashed together. Ho Dyak fought with the strength of despair, and downed one of the black-robed ones, but then he was battling three swordsmen. The young Outcast had fallen.

Suddenly a shadow fell upon the fighting men from above. An explosion sounded and a priestly warrior fell, and then another. The sole survivor raced madly away toward the fog sea's welcome shelter and Ho Dyak was glad to let him escape. He would carry the word of the terrible weapons of Earth to the watchers along the rim.

The spaceship's helicopter settled slowly to the ground. Ho Dyak hurried toward the little ship's cabin and at the same time he saw Sarn come stumbling from the jungle toward them.

"Nick of time," grinned Nelson, and behind him Ho Dyak could see Marta Gosden's startled bloodless face.

"Right you are," Ho Dyak assured the Earthman. "And how did the search for a gateway to Earth go?"

"We're not worrying about that for the present," said Nelson. "You need us, Ho Dyak, and I think we need you too. We're staying here on Thrane for a long time."

"I am glad," Ho Dyak flashed. "In centuries to come all Thrane will bless you."

"That's so much jet dust," scoffed Nelson. "But we did find a canyon, several miles deep, Ho Dyak, a sort of fog lake, where you may be able to live normally, and above it, on the second plateau we found an ideal spot for our own home."

He squeezed Marta's shoulder as she slipped past him. Then he was beside her as she greeted Sarn. Ho Dyak smiled as he felt the friendly spirit that was instantly kindled between these women of two strange races.

"She is lovely!" cried Marta to Ho Dyak and Nelson, "and so miserable. Run to the ship, Glade, and bring another space suit."

Yes, thought Ho Dyak, with the knowledge of two races his ivory-skinned race might once again spread up over the fertile chill plateaus of Thrane. Already he loved the mighty vistas of clear air here above the fog sea. Never again would he be satisfied with the circumscribed grayness of a fog-bound world....

*** END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FOG OF THE FORGOTTEN ***

This file should be named 63817-h.htm or 63817-h.zip

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/6/3/8/1/63817/

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions will

be renamed.

Creating the works from print editions not protected by U.S. copyright

law means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works,

so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United

States without permission and without paying copyright

royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part

of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm

concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark,

and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive

specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this

eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook

for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports,

performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given

away--you may do practically ANYTHING in the United States with eBooks

not protected by U.S. copyright law. Redistribution is subject to the

trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

START: FULL LICENSE

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full

Project Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or

destroy all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your

possession. If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a

Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound

by the terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the

person or entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph

1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this

agreement and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the

Foundation" or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection

of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual

works in the collection are in the public domain in the United

States. If an individual work is unprotected by copyright law in the

United States and you are located in the United States, we do not

claim a right to prevent you from copying, distributing, performing,

displaying or creating derivative works based on the work as long as

all references to Project Gutenberg are removed. Of course, we hope

that you will support the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting

free access to electronic works by freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm

works in compliance with the terms of this agreement for keeping the

Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with the work. You can easily

comply with the terms of this agreement by keeping this work in the

same format with its attached full Project Gutenberg-tm License when

you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are

in a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States,

check the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this

agreement before downloading, copying, displaying, performing,

distributing or creating derivative works based on this work or any

other Project Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no

representations concerning the copyright status of any work in any

country outside the United States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other

immediate access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear

prominently whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work

on which the phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed,

performed, viewed, copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no

restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it

under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this

eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the

United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where

you are located before using this ebook.

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is

derived from texts not protected by U.S. copyright law (does not

contain a notice indicating that it is posted with permission of the

copyright holder), the work can be copied and distributed to anyone in

the United States without paying any fees or charges. If you are

redistributing or providing access to a work with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the work, you must comply

either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 or

obtain permission for the use of the work and the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any

additional terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms

will be linked to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works

posted with the permission of the copyright holder found at the

beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including

any word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access

to or distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format

other than "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official

version posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site

(www.gutenberg.org), you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense

to the user, provide a copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means

of obtaining a copy upon request, of the work in its original "Plain

Vanilla ASCII" or other form. Any alternate format must include the

full Project Gutenberg-tm License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

provided that

* You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is owed

to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he has

agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments must be paid

within 60 days following each date on which you prepare (or are

legally required to prepare) your periodic tax returns. Royalty

payments should be clearly marked as such and sent to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the address specified in

Section 4, "Information about donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation."

* You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or destroy all

copies of the works possessed in a physical medium and discontinue

all use of and all access to other copies of Project Gutenberg-tm

works.

* You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of

any money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days of

receipt of the work.

* You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work or group of works on different terms than

are set forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing

from both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and The

Project Gutenberg Trademark LLC, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark. Contact the Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

works not protected by U.S. copyright law in creating the Project

Gutenberg-tm collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may

contain "Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate

or corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other

intellectual property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or

other medium, a computer virus, or computer codes that damage or

cannot be read by your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium

with your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you

with the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in

lieu of a refund. If you received the work electronically, the person

or entity providing it to you may choose to give you a second

opportunity to receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If

the second copy is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing

without further opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO

OTHER WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT

LIMITED TO WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of

damages. If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement

violates the law of the state applicable to this agreement, the

agreement shall be interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or

limitation permitted by the applicable state law. The invalidity or

unenforceability of any provision of this agreement shall not void the

remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in

accordance with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the

production, promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, harmless from all liability, costs and expenses,

including legal fees, that arise directly or indirectly from any of

the following which you do or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this

or any Project Gutenberg-tm work, (b) alteration, modification, or

additions or deletions to any Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any

Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of

computers including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It

exists because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations

from people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future

generations. To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation and how your efforts and donations can help, see

Sections 3 and 4 and the Foundation information page at

www.gutenberg.org

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent permitted by

U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is in Fairbanks, Alaska, with the

mailing address: PO Box 750175, Fairbanks, AK 99775, but its

volunteers and employees are scattered throughout numerous

locations. Its business office is located at 809 North 1500 West, Salt

Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email contact links and up to

date contact information can be found at the Foundation's web site and

official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To SEND

DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any particular

state visit www.gutenberg.org/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations. To

donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project

Gutenberg-tm concept of a library of electronic works that could be

freely shared with anyone. For forty years, he produced and

distributed Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of

volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as not protected by copyright in

the U.S. unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not

necessarily keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper

edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search

facility: www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.