The Project Gutenberg EBook of Lincolniana, by Andrew Adderup

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Lincolniana

Or The Humors of Uncle Abe

Author: Andrew Adderup

Release Date: April 14, 2014 [EBook #45386]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LINCOLNIANA ***

Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by the Internet Archive

CONTENTS

LINCOLNIANA; OR, THE HUMORS OF UNCLE ABE,

"Wilkie, where does Old Abe Lincoln Live."

The State House Struck by Whiggery.

How Uncle Abe got his Sobriquet.

"I'll take Number Eleven too."

Couldn't Make a Presidential Chair.

"Couldn't see It in that Light."

Little Mac Helped by an Illustration.

Uncle Abe Believes in the Intelligence of Oysters.

Why Uncle Abe Made a Brigadier.

Uncle Abe Divided on a Question.

"Thank God for the Sassengers."

Has no Influence with the Administration.

Uncle Abe Boss of the Cabinet.

Uncle Peter Cartright's Wonder.

Uncle Abe on the Whisky Question.

Uncle Abe's Estimate of the Senate.

"Thought he Must be Good for Something."

A Soldier's Theory of the War.

The Concrete vs. the Abstract.

Uncle Abe goes into Partnership.

Abe Passing Counterfeit Money.

Uncle Abe as School Superintendent.

Uncle Abe Swapped when a Baby.

Is Joe Miller "complete?" I doubt it, maugre the pretenses of title-pages. An old joke is sometimes like a piece of painted glass in a kaleidoscope—every turn gives it a new aspect, and the new view is sometimes taken for the original phase. Perhaps this is true of some herein, although I am unconscious of that being so. If the accusation be made, try Uncle Abe first, for he is used to trials. As for me, I shall plead my privilege of telling you "the tale as it was told to me." But if these "little jokes" be not "sworn upon" for Miller, they shall stand for Uncle Abe—the writer hereof claiming only a godfathership. And others shall follow as fast as I glean them. To aid this purpose, let everybody who has a "good thing" send it to the publisher of this, and duly it will appear in the "complete" edition of Uncle Abe's jokes, always excepting the last, for the act of dying over will remind him of some little story with a hic jacet moral.

Springfield, Ill., April 1, 1864.

Sometime after Mr. Lincoln's well remembered passage of the rebel Rubicon at Baltimore, some radical Republicans, who thought they saw some signs of the President's backwardness in vindicating the Chicago platform, went in committee to the White House to beg him to carry out his principles—or rather to stretch them in Queen Dido's style.

"I don't know about it, gentlemen," replied Uncle Abe; "with a pretty strong opposition at home and a rebellion at the South, we'd best push republicanism rather slow. Fact is, I'm worse off than old blind Jack Loudermill was when he got married on a short courtship. Some one asked him a few days after, how he liked his new position. 'Dunno,' said he; 'I went it blind to start with, and ain't had a chance to feel my way to a conclusion yet.' So it is with me. Perhaps you can see further than I can, to me the future is dark and lowering; and we have now got to feel every step of our way forward. Making Republicans used to be hard work, and I don't see as I could do much at it now, unless I proselyte by giving fat offices to weak-kneed opponents; but that," continued Uncle Abe, with a sly look toward several of his old Illinois friends, "would'nt be quite fair to those who believe that 'to the victors belong the spoils.' Your idea about pushing things reminds me of the first black Republican I ever made."

And the President threw his left leg over his right and subsided into that air of abandon which denotes his pregnancy of a good story.

"You see, gentlemen," he began, "in my boyhood days, I had a slim chance for schooling, and did'nt improve what I did have. Occasionally a Yankee would wander into Kentuck, and open a school in the log building that was a church and school house as well, and keep it till he got starved out or heard of a better location. One Fall a bald headed, sour-visaged old man came along and opened the school, and my people concluded I must go; as usual the big boys soon began to test the master, who, though he was a patient Jeffersonian Republican, seemed very tyrannical to us. My good nature singled me out soon, as the scapegoat of the school, and I got more than my share of the birch: at least, my back was as good as an almanac, for every day of the week was recorded there. But, though this record of past time was no pastime to me, I could stand it better than I could the taunts and jibes of the boys out of school.

"One morning when a half dozen of us were warming before the broad logwood fire, I noted a big fellow (who had got me flogged the day before) standing on the side opposite, his back to the blaze: both hands were partially open, one laid in the other; some would lay it to the devil, but it was only the spirit of revenge which prompted me to pick up a live coal, covered with ashes, and drop it into his hands. For a moment he did'nt mind it, but it burned all the deeper; when it did burn he jumped and bellowed like a stuck calf.

"'Who made that noise?' Demanded old Whitey? the master.

"'I made it,' replied the big fellow, rubbing his hands.

"'Why?' more angrily demanded old Whitey.

"'Some one put a coal of fire in my hand and burnt me,' sniffled the booby.

"The big fellow, however, didn't know who did it. Some of the boys, who had a lurking pity for me, said it snapt into his hand; but the master 'couldn't see it;' and at last it leaked out that 'Abe Lincoln done it.'

"So you see, gentlemen," said Uncle Abe, moralizing, "I got the blame of a long score of supposititious shortcomings by one act of my own, pretty much as I had to bear the sins of my whole party in the late canvass, because of a few sins of my own."

"'Abraham, come up here!' thundered the master, (By the way, gentlemen, my people always called me Abe—my wife still calls me plain Abe—but that old fellow called me Abraham so often and so severely that I early dropped all claim to a definite appellative, and chose to be indefinitely 'A. Lincoln.') * But to go on. I got a deserved threshing that time, and a reputation withal for wickedness that saved all the little rogues in school. At last, however, I determined to be even with old Whitey, somehow.

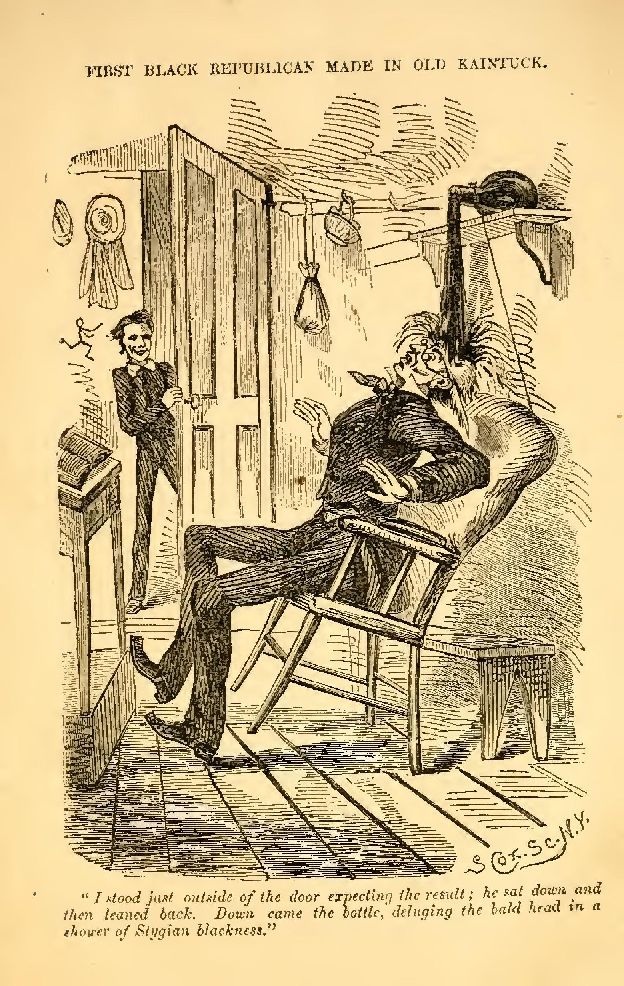

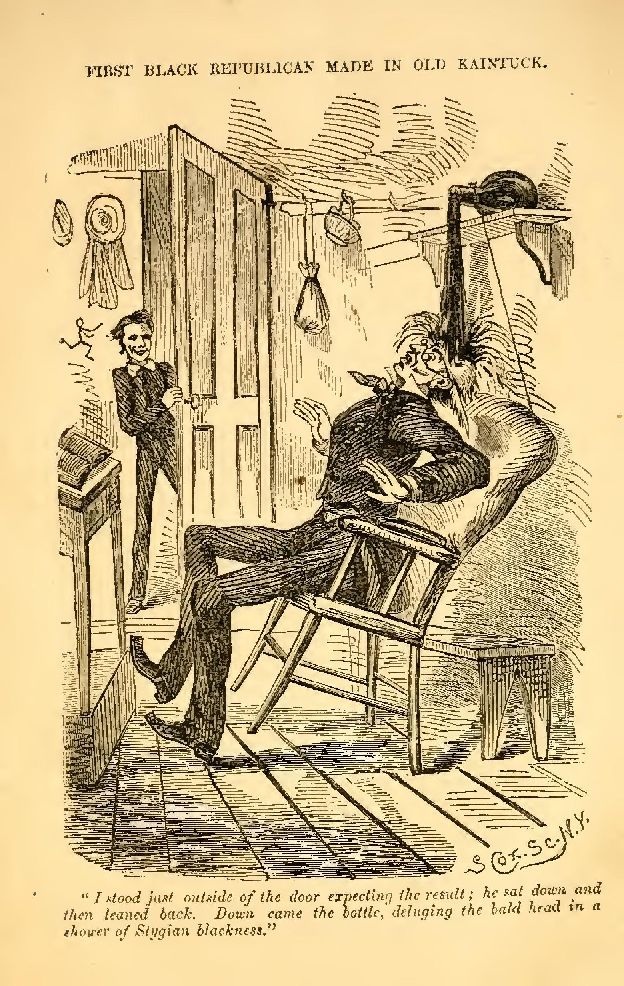

"It wasn't long till I worked out an idea. Just over the master's desk was a rude shelf, upon which he kept some books and a big-bellied bottle of ink, which some admirer of his Jeffersonian-Republican principles had presented him. I had observed that in stepping upon his desk platform, he never touched or moved his chair, beyond leaning back in it, which he always did, after taking his seat. So next day I robbed our old long-tailed white horse of a few hairs and braided them in a three stranded cord. While the master was gone out to his dinner, I put the thin glass ink bottle upon the edge of the shelf propped a-cant, and tied one end of the cord to the bottle, and the other end to the back of his chair. The boys sympathized with me, and were in an extacy of delight. Anon the master came. Without looking to the right or left, he marched sternly to the chair, and hence saw not the repressed titter of expectation that was ready to burst over the whole room. I stood just outside of the door expecting the result; he sat down and then leaned back. Down came the bottle, deluging the bald head in a shower of Stygian blackness! Yes, gentlemen, I fancy that was the first black Republican ever made in Kentuck, but the conversion was too sudden."

"How was that?" queried Cassius M. Clay.

"Why," replied Uncle Abe, "he afterwards married a widow and——twelve negroes."

* When Mr. Lincoln was nominated, very many papers ran up

the name of "Abram Lincoln."

I never knew a flash phrase worse used up than was one by Uncle Abe attending one of the neighboring Circuit Courts above Springfield. He was employed to aid a young County Attorney to prosecute some reputed hog thieves. The crime of hog stealing had become so common that the people were considerably excited and an example was determined on. The first person tried was acquitted on a pretty clear alibi or pretty hard swearing. As the fellow thus acquitted was lounging round the Court House, Uncle Abe was passing, and he hailed him.

"Well Mr. Lincoln, I reckon you got the wrong sow by the ear when you undertook to pen me up."

"So it seems," replied Uncle Abe, blandly, "but really you must excuse me, pigs are so very much alike! In fact, people up here don't all seem to know their own."

In "Clay times," as the old farmers of Sangamon still recall the period of Henry Clay's powerful canvass for the Presidency, Uncle Abe had a wide circuit practice. In travelling to the various courts, he generally drove a horse and vehicle that some people will still remember. The horse had belonged to an undertaker, and the "funeral business," together with years, had made him a grave and staid animal. His physique presented those angularities that characterized his master, but unlike his owner, he was never known to perpetrate a joke or indulge in a "horselaugh." The vehicle was neither buggy, nor Jersey wagon, but had become, by virtue of alterations and repairs, what Uncle Abe afterwards described the Union under the plan of free and Slave States "neither one thing or the other." There was in fact an "eternal fitness" in horse and man that was not exactly a "standing joke," but a peripatetic one.

I would give all my expectation of a brigadiership for a portrait of Uncle Abe seated in this strange "turnout," as he "might have been seen" wending his meditative way across the prairies.

About this time Uncle Abe was nominated for Congress in the Sangamon. Yet he did not forego his business, but prosecuted his legal course, as well as all evil-doers who chanced to fall into his hands. He had just started on a circuit trip, to be gone a month. Often, since Mr. Lincoln's nomination for Congress, had Mrs. Lincoln begged him to add a second story to their humble dwelling, but he pleaded poverty. But a relation of Mrs. Lincoln's having died in Kentucky leaving her a small legacy, she determined her husband should have a house worthy a candidate for Congress. Doubtless she felt an inward satisfaction at the thought of furnishing a good surprise for her husband on his return. So she at once bought material, set mechanics at work, and in three weeks metamorphosed the dwelling into what political pilgrims to Springfield in 1860 will remember as a neat, two-story, clay-colored residence.

Uncle Abe arrived home just after dark, and drove up to what he thought to be Eighth street, but not seeing his house, and thinking he had made a mistake, he drove round on to the next street. Recognizing the houses there; he again drove around to Eighth, and, passing his own house, recognized that occupied by W———n, a clever tailor, who was standing at his own gate.

"Why, is that you, Wilkie?" (said Uncle Abe patronizingly.) W———n, assured him of his own identity, "Wilkie, where does Old Abe Lincoln live now."

"Well," said W———n, "The Loco's say he's so sure of his election that he's gone to Washington to select his seat; but Mrs. Lincoln lives now in that beautiful new two-story house you have just passed." Uncle Abe indulged in a quaint laugh, and then turned his ancient horse around, alighted and asked if Mrs. Lincoln lived in the house before which he stood. Mrs. Lincoln received him as a fond woman should receive her lord, and the return was the cause of much pleasant badinage in social circles.

Gen. McClellan was complaining to Uncle Abe of one of his division commanders, who had literally obeyed an order publicly given for the purpose of hood-winking the rebels through the aid of the numerous undetected spies known to lurk in the camp as well as the capital.

"That reminds me of a little story—a little thing that happened to me when I was out in the Black Hawk war," said Uncle Abe.

"You see, after we brought the Foxes to terms, they were as sweet as wild honey. The women especially tried to make a good thing out of the defeat of their braves, by selling us moccasins, deerskin breeches, &c. One squaw in particular, made beautiful breeches, and I concluded to have a pair made. How she was to fit my spindles, puzzled me at first, as the Indians are no tailors in any measurable degree. At last I bethought me of an old pair which I had in my saddle bag, and these I gave to her that she might rip them open and use the parts for patterns. When she brought the new ones home, I was not a little angry to find that she had exactly imitated the old patch on the nether parts of the new breeches."

Little Mac smiled in his peculiar grave way, and remarked that when he gave an order for a similar purpose, he would tell this story by way of a hint.

Soon after Uncle Abe's defeat by Judge Douglas in 1848, (whereby Douglas unwittingly made a President) some one asked Uncle Abe how he felt over the result.

"Well," said he, "I feel a good deal like a big boy I knew in Kentuck. After he'd got a terrible pounding by the school master, someone asked him how he felt? 'Oh! said he, it hurt so awful bad, I couldn't laugh, and I was too big to cry over it.' That's just my case."

It is presumed the questioner got an idea how a defeated politician feels.

Soon after the advent of Uncle Abe at the White House, the pressure of aspirants for official positions was perfectly crushing.

In fact, Uncle Abe sometimes got so flustered by their bedevilment, that he not only failed to recollect an illustrating anecdote, but soon lost his temper.

One of the Illinois applicants—a fellow named Jeff.

D———r, was particularly a bore, seeming to think it part of the Chicago platform to give every village politician an office.

"Seems to me, Jeff," said Uncle Abe, "you got the Chicago platform reduced to enormous brevity—in fact, just three p's would seem to express your idea of it."

"How's that, Mr. Lincoln?" inquired-Jeff.

"Why, it looks to me as if it was patriotism, place and plunder, and a mighty important plea is the last one, I reckon."

Jeff was silent for a while, but bored on until he "struck ile" in the shape-of a clerkship.

Just after the retreat of the rebels from Bull Run, when it leaked out that our troops had been held at bay by wooden or Quaker guns, a Pennsylvanian Congressman remarked to Uncle Abe—"Well, Mr. Lincoln, you see that Quaker principles even embodied in wood may be of some service in war."

"Yes, but as you see in that shape, they are only substituted principles; such things may do once, but found out, they will avail worse than nothing. Your remark, however, 'reminds me of a little story.'

"When I was a youngster of fifteen or so, I went to an 'Academy' for a few weeks, just to brush up my old-field school learning. Such schools are called Academies in the East, to distinguish their intermediate position between colleges and common schools; but in Kentuck and the West, generally the high sounding title merely meant that the 'principal' taught a few branches ahead of the old-field schools. Well, the rats were thick about the old building where we daily gathered to reap the fruit of knowledge; and as many of the boys brought their dinners and threw the fragments under their old-fashioned box desks, they soon grew as bold as they were thick. The teacher had a mortal antipathy to rats, and as I didn't 'take' to the teacher, I naturally encouraged the rats. Whenever one showed himself, he was sure to get a whack from the old teacher's rattan. Sometimes he missed his aim at the rats, but never at us boys, which was owing, perhaps, to the difference in the size of the game.

"An industrious rat had made a hole from beneath the floor up under my desk, and thence out through the end, and as I fed him well he was quite tame. Often during school hours he would come up and peer out into the aisles through his hole in the end of the desk, and whenever he was seen by the teacher, he was sure to see the rattan whirling in the air. An idea struck me one day. I got a dead rat—I did not like to kill my pet—and stuffing it, made quite a good-looking 'Quaker' rat. Then I fixed some springs so I could work my rat out and in at pleasure; so whenever the teacher was looking up, my rat was always out; but when the whack came down, he was in betimes. At last he seemed to think it wondrous tame, and the ill-suppressed titter of the school boys finally made him suspicious. The boys had been let into my secret, and relished it hugely, and I was too prone to give a few exhibitions. At last the teacher watched me sharper than he did the rat, and then caught me in the act. He got hold of the rat and beat me alternately with rat and switch, and you may well guess, I was well rattaned. If soldiers who use wooden guns ever get worse usage, I pity them."

The 300 Pounder Parrot since used by the Government, shows Uncle Abe's poor appreciation of Quaker guns and Quaker principles.

Soon after the State House at Springfield was erected, in 1840, Mr. Lincoln stood on the east side of the Capitol Square one day, in conversation with a Democratic friend, who was loth to believe that the Whigs could carry the State for "Tip and Ty."

"Nothing is more morally certain," said Uncle Abe. "All the signs of the times point to it, and—why even the State House is struck with Whiggery" he said, pointing up under the eves, where is yet seen a remarkable representation of a "coon" in the stone.

When Hon. Emerson Etheridge escaped from Tennessee during the summer of 1862, his opinions on Tennessee affairs were eagerly listened to in Washington. Among other questions, Uncle Abe asked:

"Do the Methodist clergy in your State take to secession?"

"Take? Why, sir, they take to it like a duck to water, or a sailor to a duff kid."

Judge David Davis of Bloomington, Illinois, who was recently appointed (by Uncle Abe) to a position on the bench of the Supreme Court of the United States, is known to many of his friends as one of the best hearted men in the world. His, is withal, full of the piety of good humor. I call it "piety," because I think a smiling face is a perpetual thanksgiving to God. His benevolence, however, edges down his wit, and gives it more the characteristic of humor, strictly speaking. This, while it may have helped that "belly with fat capon lined," has kept him at peace with himself and the world.

On one occasion, while Judge Davis was presiding at the Logan County Circuit Court, a case came up that involved a question of postal law. Uncle Abe was on the case, and politely loaned Judge D. a small manual of postal law, that he might see for himself what the letter of the law was. The Judge gave his understanding of the law, but had hardly finished when Mr. S———s, a burley farmer from Clear Creek, jumped up and sang out—

"I reckon that ain't so, Judge. I've been Post-Master more'n a dozen years, and I reckon I ought to know what's Post Office law."

Of course Judge Davis had every right to fine the man for contempt, but he had a different way of treating such cases. "With a tone in which sarcasm only slightly blended, he said:

"Truly, I think you ought, Mr. S———s. It has never been my privilege to be a Post-Master, and I would like your opinion in this case. Please step this way."

The Judge moved over and made room on the bench, which Mr. S———s occupied, and proceeded to give his opinion on the mooted question. The bar sat smiling in expectation.

"Keep your seat, Mr. S———s, while I speak a word with my friend Parks."

Uncle Abe it was who had been interrupted, so he resumed:

"May it please the Court, I had some doubt on this point myself, so I borrowed the usual manual of Postal Law, to be perfectly assured. I regret to contend that the clear letter of the law conflicts—sadly conflicts—with the view just taken by Judge S———s;" but here the bar indulged in a quiet "smile" without a stick in it, and it just popped into Mr. S———'s head, that he was out of place, and he skedaddled in haste.

"The largest pussie Judge that sat on our bench," remarked Will Wyatt. From that day to this, Mr. S———s, has never lost the title he so suddenly gained.

One day while Uncle Abe was attending to a case at Mount Pulaski, (the country seat of Logan County, Illinois,) he was beset by old B———s, a worthy farmer, but a notorious malaprop, for an opinion as to his amenability to the road tax. "You look here, Mr. Lincoln, these fellows here want to make me work on the road."

"Well!" said Uncle Abe.

"Well, I tells them that they can't do it, cause I'm an inderlid, you see."

(Of course Uncle Abe concurred in B———s opinion, and forgot to charge a fee.)

"On another occasion, he wanted John G. Gillette, the great cattle dealer, to proximate him because he'd got the best pair of cattle scales in Logan County."

Some one ventured to ask Uncle Abe, soon after his arrival at the White House, how he got the sobriquet of "Honest Abe."

"Oh," said he, "I suppose my case was pretty much like that of a country merchant I once read of. Some one called him a 'little rascal.' 'Thank you for the compliment,' said he. 'Why so?' asked the stigmatizer. 'Because that title distinguishes me from my fellow tradesmen, who are all great rascals.'"

"So honest lawyers were so scarce in Illinois that you were thus distinguished from them?" persisted the questioner.

"Well," quoth Uncle Abe, glancing slyly at Douglas, Sweet, and others from Illinois, "it's hard to say where the honest ones are."

Thirty-five or forty years ago, a trip from Sangamon or Macon County, to St. Louis, was an event to be talked of. It took as long to make it, and furnished food for as much rustic enquiry and comment, as does a voyage to Europe now. Uncle Abe had then given up rail-splitting, and was studying law. Having a little while before treated himself to a (then) rare thing, a suit of "store clothes;" and a neighbor being about to leave for St. Louis, he resolved to go along. As the teams toiled on at the rate of fifteen or twenty miles a day, they were gradually joined by others, till the train presented somewhat the sights now to be seen on our great overland routes to the Pacific.

On arrival at St. Louis, Abe determined to see high life, and accordingly made tracks for a letter A. No. 1, first class Hotel. The Old City Hotel was then the only house that could claim that distinction. There the merchants congregated, and there the Indian trader sought relaxation from frontier hardships, while the rough trapper was content with the humble fare of the "Hunter's Home."

I forget what association called out this reminiscence of that trip; but there can be no harm in repeating the story. Such mishaps have befallen incipient greatness before.

At the dinner table, each waiter was provided with a wine card, and each guest had his wine charged to the number of his room, simply calling out, as for instance, Sherry No. 9, &c. A jolly Indian trader, sat just opposite Abe, who betimes called "Claret, No 11." Abe saw that most of the guests were similarly providing for themselves, and concluded not to appear penurious, so he said he'd take some wine too.

"What kind, sah?" asked the waiter.

"Oh, I'll take the same,"—pointing to the bottle just called for by the Indian trader.

"What number, sah?"

Abe was puzzled. Ho had not been used to wine or hotel life; but it was only a moment before he broke the ice.

"Oh, I'll just take No. 11 too."

The trader looked up surprised, while several others near by, smiled a faint comprehension as to the state of affairs.

"Why, young man," said the trader, "that is my number, and mine is a single room."

"I beg pardon," stammered Abe, conscious that he had betrayed rusticity and ignorance; but not knowing exactly how to extricate himself, the good-hearted trader came to his aid—

"Were you ever in the city before?" asked he.

"Never before."

"Well, then, in memory of your advent, it shall be No. 11 too," and he quietly pushed the bottle across the table. So agreeable was he that Abe rallied, and the second bottle followed the fate of the first. On renewing the conversation after dinner, the trader was satisfied that Abe had 'lots' of 'horse sense,' but little of worldly experience, and he friendlily invited him to go out with him as a clerk; but, Abe declined. Had he gone—what? Perhaps he might have become a respectable Indian trader—perhaps he never had been elected President, and perhaps we would have had no rebellion.

Uncle Abe took a great liking to the late Col. Ellsworth, and afterwards did him the honor of making a Colonel of him. The rebel Jackson did the rest, but enough of that. Many of our readers will recall the slim, spruce figure of Col. Ellsworth as he paraded the streets of Springfield, dressed in a unique Zouave uniform, a mere boy in appearance. He was full of animal spirits. He and Bob O'Lincoln were cutting up didoes in the Law office of Lincoln and Hornden, which greatly annoyed Uncle Abe, and he gently reproved them. Bob, a little nettled, replied by quoting the common couplet:

"A little nonsense now and then,

Is relished by the wisest men."

"Yes," said Uncle Abe, looking severely at Bob, "that's the difference between a wise man and a fool who relishes it all the time."

Bob subsided, and Ellsworth betook himself anew to Blackstone.

When Uncle Abe used to attend the Courts in the regions round about Sangamon, he generally made easy stays, and was wont to look at the country and talk to the people at his leisure. On one occasion he was riding by the premises of old H———, who was notorious for his unthriftiness, and who was in the act of driving some stray hogs out of his corn-field.

"Good morning, Mr. H———," said Uncle Abe.

"Morning, Mr. Lincoln, morning."

"Why don't you mend that piece of fence thoroughly, Mr. H———, and keep the pigs out?" asked Uncle Abe.

"Ha'n't got time," said H———.

"Why," said Uncle Abe, with an air of blended reproof and humor, "you've got all the time there is Mr. H———."

Whether H——— mended his fence and his thriftless habits, this deponent knoweth not; but has often thought how true was the remark, whether as a joke or an admonition. Every second, minute or hour is ours—ours to use or ours to squander. How wontonly wasteful would be the rich man who should stand upon a vessel's deck and cast his million golden coins into the sea; yet day after day we stand upon the shores of eternity, and cast the golden moments into the unreturning past. All the knowledge and wealth of the world is but the result of improved time. So don't say you "havn't got time," for you've got all there is, as Uncle Abe says.

About the time this occurred, there stood on one side of Capitol Square, in Springfield, a Hotel, now doubtless out of memory of most of the occupants of the out-lots and additions which speculators have hitched to the original village. In its day it was a "first-class hotel," but it waned before the "American" and is now among the "things that were." There were some who doubted the cleanliness of the cuisine, and "thereby hangs a tale."

Judge Brown arrived in town and put up at the aforesaid hotel, whereat, Uncle Abe, on meeting him, expressed his regret, begging him to become his guest. The Judge would fain not trouble his friend.

"But you know the reputation of the place—the kitchen?" said Uncle Abe.

"I've heard of it," said the Judge; "but as I want to keep my appetite, I always shun the kitchen, if not the cooks."

"But surely, can't you see by the table alone, Judge?"

"I know, Mr. Lincoln, but I'm going to stop only a day or two, and I guess I can stand for that time what the landlord's family stand all their lives."

Speaking of Hotels, reminds me of a little episode of one of Uncle Abe's professional visits to Cairo, in Egypt, a town fenced in with mud-banks and celebrated for its mud-holes and mean whisky. Thereabouts is a Hotel, and thereat Uncle Abe stopped because the water forbade further traveling. When his bill was presented to him next morning, he ventured to remark, "that his accommodation had not been of the most agreeable kind."

"We are very much crowded," apologetically replied the landlord.

"But I had hard work to get breakfast this morning."

"Yes," continued the apologist, "we are greatly in need of help."

"Well, well," said Uncle Abe, "you keep a first rate hotel in one respect."

"Ah!" said the landlord, brightening up, "in what respect is that?"

"Your bills," said Undo Abe, vanishing towards the "Central" cars.

The Ky-ro-ite landlord perhaps thought he ought to be well compensated for keeping a hotel in such a place. A man of his sort used to "keep tavern" in Pasy County, Indiana, several years ago. A pedestrian stopped with him over night, for which the charge was 2.50.

"Why, landlord," said he, "this is an outrageous bill."

"You mean it's a big'un?" said the insatiate Boniface.

"Yes, I do."

"Well, stranger, we keep tavern here."

"What has that to do with such a bill?"

"Look at that'ere sign, stranger—cost ten dollars; your'n the fust trav'ler that's bin along for three weeks, and we can't afford to keep tavern for nothin—we can't!"

Gov. Morgan, of New York, was urging the employment of General W———in active service, Seward objected, that he was "too old" for the emergency of the times.

"Yes," said Uncle Abe, "we've got too many old officers in the army, and that is not the worst of it—we've got two many old women there!" This was when Uncle Abe's faith was strong in little Mac.

"Some conclusions;" said Uncle Abe on one occasion, "are nonsequential. To say that Rome was not built in a day, does not prove that it was built in a night."

In the outset of the famous Black-hawk war in Illinois, a "hoss company" was raised in the region where Uncle Abe was (then) a rising lawyer. I say rising, although he had then reached a height sufficient to help himself to most blessings—and he, the aforesaid U.A., was chosen Captain. Uncle Abe rode a "slapping stallion," who was either naturally restive, or appreciated his new honor too highly—at any rate, he corvetted and pirouetted like a very Bucephalus. At last he unhorsed his rider, who landed sprawling on the prairie in one of those green excrescences that abound where bovine herds range. As the discomfitted Uncle Abe rose, and surveyed his predicament, old Pierre Menard, who was a near spectator, remarked in his broken French:

"Vell, I nevair sees any man accoutred en militaire like zat before."

Most old suckers pronounce accoutred as the Yankees do the word cowcumber, and this rendered Menard's joke more unctious.

Years ago, when the capital of Suckerdom was a village of less "magnificence" than it now presents—when Lincoln, Harden, Baker, McDougal, Douglas, Shields and Ferguson were all village lawyers, and scarcely known to fame—Judge Thomas Brown was on the Supreme bench of the State. He was to some extent a "character;" but not a very successful lawyer. He went to California, since when he has been generally lost sight of; but his old friends may be assured that if he is in the "land of the living," Uncle Abe's tax collectors will find him. But that's neither here nor there. His ideas of the perils of practicing law in Illinois, in early times, is what is now before the reader.

On one occasion, after he had changed his residence to Peoria, having some business to transact in Springfield, he arrived in that place and put up at the old American House, (now kept by Henry Bidgely, Esq.) He chanced to mention the name of Peoria. Instantly the attention of a countryman was fixed, upon him, who, at the first opportunity accosted him—

"From Peoria, Squar?"

"Yes."

"Much acquainted?"

"Pretty well, Sir."

"Know a lawyer up there named H———g R———s?"

"Yes sir."

"How's he getting along?"

"Oh, first rate—devilish lucky man."

"He's getting hold of considerable land, hain't he?"

"Yes a deal—devilish lucky man.

"Yes—large—devilish lucky man."

"Look here, Squar," said the countryman, evidently puzzled at R———s being so devilish lucky.

"What do you mean about his being so lucky?"

"Mean? why I call any man lucky that practices law twenty years in Illinoiss, and don't get into the penitentiary."

"Mr. Lincoln," said an ardent sovereignty man just at the beginning of the last Presidential contest "Mr. Douglas is a cabinet maker."

"He was when I first knew him," said Uncle Abe "but he gave up the business so long ago, that I don't think he can make a Presidential chair now." Uncle Abe proved himself a prophet, although at a tremendous cost to the country.

A delegation of temperance men recently sought to influence Uncle Abe to take some stringent steps to suppress intemperance in our armies. Among other reasons urged, they said our armies were often beaten because of intemperance.

"Is that so?" said Undo Abe. "I've heard on all sides that the rebels drink more than our boys do, and I can't see why our boys, who drink less, are more liable to get whipped."

"But you know the corrupting influence of the army in regard to drinking habits," pursued the Committee.

"I've heard that, too," said Uncle Abe, "but I think they will do pretty well if I can keep them out of Washington!"

The Committee didn't carry their measure, by a jug full.

When the Illinois boys gathered at Springfield, under the call of the ten regiment bill, they were quartered on the fair grounds, just out of the city. All the stalls were filled with troops, before which were signs as "St. Nicholas," "Richmond House," etc., etc. Charley W———, on going through the fair grounds, looked into the "Richmond House," and said—

"Well, boys, how do you get along?"

"Oh, first rate," replied the Chicagoians, "we're all stall fed."

"Bully for you," said Charley; "hope you'll be too tough for the rebels."

"I can't seem to reap any advantage from the rebel movements," said McClellan, in consultation with Uncle Abe.

"Oh, you just keep a watchful, careful eye on Leer and perhaps you will yet see how to make use of them, as old Mother Grundy did of her crooked wood."

"Thereby hangs a tale," remarked little Mac, with one of his peculiar, quaint smiles.

"You're right, General. Your remark reminded me of a good old neighbor of my father's, in Kentucky, who died many years ago. She was sweet-tempered—few such in this world." Uncle Abe stopped as though a mental comparison had damaged some woman of his acquaintance. "Yes, her disposition was of that kind that extracts 'good from things evil.' And she was her husband's pride and boast. One day he was praising her to a neighbor."

"'Look here, old man Grundy,' said the neighbor 'these women are just like cats—they are all right as long as you stroke the fur the right way, but reverse the movement, and you'll see the fire fly. Now, I'll tell you what, I bet a four-gallon keg of my four-year-old peach, that I can tell you how to make her as mad as a set-hen, if you dare to try."

"'Done,' cried old man Grundy.

"'Well, you just haul home all the crookedest sticks of wood you can find, and then see.'

"Old man Grundy brought home a small load every day or two, and it was knotty and crooked as a pigs-tail; but not a word or look of complaint. For a week this continued, with the same result, when he asked the good wife how she liked the wood."

"'Oh,'tis beautiful wood,' said she; 'it burns finely, and then it fits around my pots and kettles just, as if 'twas made on purpose.'"

Lee did not fit into Mac's hand so well, yet the story was not without its use to him.

During the progress of the Senatorial campaign between Douglas and Lincoln, Uncle Abe came home to recreate a few days. Douglas, long used to the political arena, bore the fatigues of the canvass like a veteran. His custom was to bathe just after supper, getting some friend to rub him like a race horse, when he would sit down and enjoy his whisky and cigar. Lincoln, lank and abstemious, bore his yoke with evident weariness. But to the story.

Uncle Abe went up into the Governor's room in the State House, where he was soon joined by many of the leading Republicans of the town. Some one remarked on his look of weariness. "It is a mighty contest," remarked Uncle Jesse Du Bois.

"But Mr. Lincoln does not show his great appreciation of it upon the stand," remarked a Chicago correspondent, in allusion to Uncle Abe's good humored replies to Douglas.

"But still, when the day's gladiatorial combat is over, it seems to me, as the Kentucky fellow said, that I had been through 'an acre of fight.'"

"Give us that story, Abe," said Dr. Wallace, Uncle Abe's brother-in-law.

"Well, one of my earliest recollections of a Kentucky Court, was a trial about a fight. It took place in the Court House grounds, and the Judge, thinking it constructable as a contempt of Court, sent out the Sheriff, and had the parties quickly brought before him. Both had bruised noses and beavers, and showed the unmistakable evidence of having been in a scrimage. The witnesses were numerous, and the evidence was so conflicting, that the Judge declared he could legally reach no other conclusion than that there had been no fight at all. But the Sheriff ventured to suggest:

"Here's Jim Blowers—he had hold on one of them fellers, when I arrested them."

"Mr. Clerk," said the Judge, "you will at once swear Mr. Blowers."

"Now, Mr. Blowers," said the Clerk, "you will please tell the Court what you know about this affair."

"Well, ax on."

"Well, was there a fight between these parties?"

"Just a bit of scrimage."

"It was a real fight, was it?"

"Well, some people would call it that."

"How much of a fight was it?"

"Oh, considerable—they pulled and hauled about kinder like two cows when they lock horns."

"But, tell the Court more precisely?"

"Well, I should say it was a right smart fight."

"But how much of a fight?"

"Well, then, just about an acre, I reckon."

It is needless to say that the crowd enjoyed the joke hugely.

"It is easier to pay a small debt than a larger one."

In the year 1860 or thereabouts, when a great patent case was being tried in Chicago, and champagne and oysters were the favorite viands served nightly to Counsel and Jurors after the adjournment of Court, it happened that one Ed. D———n, a young patent lawyer from New York, was present on one of those occasions. Now, Ned is terribly afflicted with a determination of words to the mouth, and managed to monopolize the whole conversation. Ned had a speech to make upon everything, and kept buzzing around like a musquito, dipping his bill into everything animate or inanimate, no matter which. At last he began to officiate at serving out the oysters, and with ladle in hand, said in his usual stilted style, "I wonder whether this bivalve, this seemingly obtuse oyster, is endowed with any degree of intelligence." Uncle Abe looked at the puppy, who, by the way, had prevented him cracking a single one of his favorite jokes for the entire evening, and quaintly remarked, that "he was satisfied that an oyster knew when to shut up, and that was more than some New York lawyers knew." Ned has never propounded the query as to the intellect of oysters since.

The last county made in Illinois—I don't mean by the Legislature, but by Nature, and where dirt was so short that it lies under water part of the year—is called Alexander, and used to boast two rival towns, both thoroughly Egyptian in their nomenclative association—Cairo and Thebes. Twenty years ago Thebes was the "seat of justice;" but Cairo was then beginning to entertain magnificent expectations, and her citizens wanted to have the Court House removed to their town. The contest waxed warm. The Thebans contended that Cairo was only a "daub of mud on the tail of the State," while Thebes was destined to hold the same relation to Alexander, that its ancient namesake did to Egypt in the time of Menes. [See Herodotus.] But to settle the dispute, the Legislature must be appealed to, and that involved the choice of a man favorable to the change. This narrowed the fight right down to a hot county canvass between the Theban and Cairoine interests.

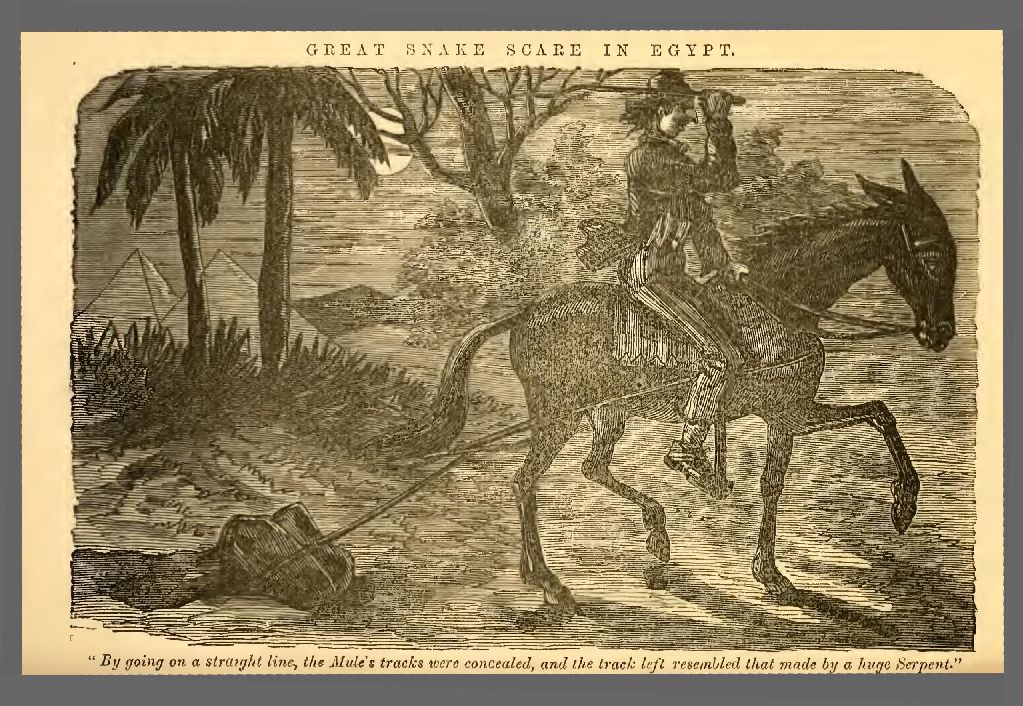

A Cairo man conceived a scheme that was ahead of anything yet achieved by Uncle Abe's brigadiers in the way of "strategy." He wrapped a boulder in a green hide, making a perfectly round mass, to which he attached a mule; then night after night he drew the stone through sand and mud. By going on a straight line, the mule's tracks were concealed, and the track left, resembled that made by a huge serpent.

These tracks were mainly in the south end of the county, and caused an excitement that almost absorbed the election interest. Soon it was reported that Mrs. so and so had seen a huge snake. The wonder grew apace. Anon it was currently reported that two men had seen the great serpent five miles above Cairo. The excitement increased. Several daring hunters followed the track, of which new ones were made every night; but the trail always led into water and was lost. Several persons missed hogs and calves, which were surmised to have gone into the capacious maw of the serpent. Finally word was given out that a great hunt was to come off in the lower part of the county, and the rendezvous was appointed. On the morning, hundreds were there from all parts of the county, and dividing into squads they started to scour the country about. At night they returned from their snakeless hunt, but so anxious were the people to get rid of his snakeship, that they furnished an abundance of edibles and whisky. All were in hilarious spirits, determined to renew the hunt on the following morning. By daylight the hunters were again on the tramp, and men from the lower part of the county happened to fall into the squad.

About 3 o'clock in the afternoon, a squad of the bans hove in sight of a small village, i.e. one house a blacksmith shop and a grocery, where, seeing a large crowd assembled, they hurried up in expectation of seeing the dead monster. But the men were voting!

"Thunder!" cried a Theban, "this is election day, and I'll bet my bottom dollar we're sold!"

They started for the rendezvous and spread their suspicions; but so few reached their own precincts, that the Cairo man was elected.

Then the joke came out; but the Thebans couldn't see the "laughing place;" their rage and mortification was so intense.

Uncle Abe was a member of the Legislature, when an effort was made to change the county seat of Alexander; and though he liked the joke hugely by which the Thebans had been "diddled," he saw the honesty of the thing and so voted against any change.

When the rebellion had gone so far as to give the most hopeful some clear idea of its extent and malignancy, it chanced that J. A. Mc———d, a leading politician of Illinois, made a visit to Washington, and imitated his friend Douglas so far as to call upon Uncle Abe. The "shoot" that certain prominent Democrats gave indication of taking, by talking of reconstruction and a Northwestern Republic, gave the new administration some concern. Uncle Abe was very sociable with Logan, Mac, and a few of their "ilk." So Uncle Abe not only extended to Mac the hospitalities of the White House, but accompanied him on a visit to the arsenal. While there, their attention was drawn to some muskets which the speculators had furnished to Cameron, and which were thought (generally) very dangerous to those who used them.

Mac caught up one, and sighted along the barrel.

"Do that again, Mac," said Uncle Abe.

Mac complied. Uncle Abe was evidently struck with an idea, and Mac was anxious to know what it was like.

"Why, Mac," said Uncle Abe, "I was thinking if we could get all our soldiers to make up that kind of a face, that the rebels couldn't stand it a moment." Mac didn't relish Uncle Abe's joke, as he was hopefully in pursuit of the third wife; but he put the best face he could upon the matter, and remarked to Uncle Abe—

"Perhaps you'd better make me a Brigadier then!"

"And why not?" asked Uncle Abe.

Mac got his commission.

Uncle Abe was met one day near Springfield, by a conceited coxcomb, who had built him a house at some distance, and invited him to dinner. Uncle Abe did not much relish the Jackenape's acquaintance. In fact, as Justice Shallow has it, had "written him down an Ass." However, Abe enquired very minutely, where Snooks lived? "Thistle Grove," replied the verdant Snooks; "but there's no grove now, and not a single thistle!"

"Eh, what!" cries Uncle Abe, "not a single thistle! Then what on airth do you live on?"

In 1840 or '41, Uncle Abo was a member of the Illinois Legislature. The Capital had lately been removed from Vandalia to Springfield. The Legislature met in the Presbyterian church.

I have forgotten what measure was before the house; but it was one in which there were many members who did not wish to commit themselves. Uncle Abe was in this predicament. He sat near an open window, and when the clerk, calling the ayes and nays had got down to L's, Uncle Abe thrust his right leg out of the window, and was just drawing its long companion after it, when an anti-dodging member "seeing the game," shut the sash down and held Uncle Abe in a trap.

"Lincoln," called out the Clerk.

"Mr. Speaker," said Col. Thornton, "Mr. Lincoln is divided on this question, and I move you that the sergeant at arms be sent to bring in that part of him that is out of the window."

Uncle Abe was "brought in" amid a universal titter, to his evident mortification.

In 1840, the Union generally went for Harrison; but Illinois, particularly, was democratic. When the Legislature met in the Fall of that year, the Whig members tried to break up the new Session by absenting themselves from voting to adjourn the old Session sine die, so that they could Constitutionally meet the next Wednesday morning; the State Constitution requiring the Legislature to meet "the first Monday in December next, ensuing the election of members." After the breaking up of the morning Session, the Sergeant-at-arms hunted up the delinquent Whigs, and at 3 o'clock there was a quorum obtained, and the doors locked. The Springfield Register of Dec. 11, 1840, mentions this matter, but thinks Uncle Abe "come off without damage, as it was noticed that his legs reached nearly from the window to the ground!"

A proposition was afterwards humorously proposed, to add another story to the new State House, so that fugacious members would have to go down the water spouts if they ran!

Thirty years ago, when Springfield was blooming into the dignity of its Capitalive position, the American House was its great hotel, (and it isn't its smallest yet,) and the resort of those who loved to spend a few hours in the society of the bon vivants who then assembled—Lincoln, Douglas, Shields, Ferguson, Herndon, (then a young man, but since the law partner of Uncle Abe,) and many others "not unknown to fame," could almost always be found here during the evening.

One evening as they were sitting in free converse in the bar-room, one of the chamber maids came in and informed the landlord that a man was under her bed.

It seems while stooping down to untie her gaiters, she saw a man under the bed. With rare presence of mind, she excused herself to her fellow servant as having forgotten some duty, and reported her discovery to the landlord. Boniface at once called for volunteers to secure the interloper. So eager were they for fun, that all volunteered. They surprised and captured the man, and brought him down to the bar-room; but what to do with him? was the next question. Springfield then had no vagabonds who made fees out of misfortunes—i.e. policemen—and it was determined to treat him with the prompt justice peculiar to that era. A court was therefore got together at once, all expectant of fun but the unfortunate culprit.

Judge Thomas Brown was decided upon to act as Judge; Melborn, the talented, but eccentric State Attorney, was detailed to prosecute; and Lincoln and Douglas to defend the prisoner. Dr. Wallace acted as Sheriff, and upon the jury were Dr. Merriman, * Gen. Shields, John Calhoun (of Lecompton memory,) Uri Manly, and many other well known personages.

Lawborn, though a regularly-educated and talented lawyer, took occasion not only to be as "funny as he could," but to imitate the prevailing style of oratory too common in Illinois—a style in which the Hard-shell-Baptist devil mingled with the rough dialect of the back-woodsman.

"May it please your Honor, and you, gentlemen of the Jury: The Legislature of Illinois, though it has legislated upon every subject it could think of, has omitted to pass any act against a man being born as ugly as he pleases. If such an idea ever occurred to my friend Lincoln here, when in the Legislature, I know he would at once dismiss it, not only as too personal, but as repugnant to his honest heart. As for myself, I like ugly men. An ugly man stands up on his own merits. Nature has done nothing for him, and he feels that he must labor to supply the deficit by amiability and good conduct generally. There is not an ugly man in this room but has felt this. A pretty man, on the contrary, trusts his face to supply head, heart and everything. He is an anomaly in nature, as though the productions had been at fault as to sex, and sought to correct it when too late. They are girl's first loves, and doting husband's jealous bane. I confess I don't like pretty men half so well as I do pretty women.

* Afterward murdered and robbed on the Pacific.

"No, gentlemen, ugliness is nothing. It is manners that is everything. The ugliest man that ever lived, never intentionally frightened a woman—nay, never was so unfortunate as to do so. But this creature, gentlemen of the Jury, this mendacious wretch whom you set in judgment upon—this creature, who would doubtless enter for a prize of beauty at a vanity fair—how has he failed in his duty to society? Why, gentlemen, by crawling under the bed upon which two fair damsels were about to expose their loveliness to Diana's envious gaze. Did he wish to woo them? Petruche's was rough in his wooing—this man was mean! Woman loves not surprises. Their hearts are fond of open sieges. This is the case of all women-kind. Maugre the slander of Hudibras:

"He that woos a maid,

Must lie, love, and flatter."

"It is a mystery that adds to beauty, and the woman who surrenders that to importunity or surprise, has lost half her vantage ground. The story of Guyges and Candaules' queen, if not paralleled here, is not without its moral. What else meant this wretch, gentlemen of the Jury, but to surprise these charming damsels when only armed with the light shield that the Huntress and the cotton plant throws over earthly beauty? Or, perhaps he meant more—his own guilty heart can only accuse him there.

"Gentlemen of the Jury, the failure of our Legislature to provide a specific punishment for such miscreants, as this—lecherous creatures, who steal upon woman amid the mysteries of the bed-room—is no reason why society should fold its arms and leave woman's hidden beauties to be anatomized by guilty eyes. No, gentlemen of the Jury, outraged decency cries for its victim, and here he tremblingly, guiltily stands.

"Gentlemen of the Jury, where are the spirits of the fathers of the Constitution? Are they not hovering over us in the air of the still summer day? Are they not wailing upon the winds that sweep over our prairies? Are they not heard in the sigh of the mountain pine? Are they not abroad in all lands, whispering to earth's downtrodden millions like a voice of hope? Yes, gentlemen of the Jury! and where was this creature then? Why, creeping under the bed of two girls, hazzarding the chance of overturning—well, it matters not."

—And much more, in a view that needed to be heard to be appreciated.

Lincoln followed, illustrating with anecdotes meet for the place and occasion, of which I recollect only the opening. "Gentlemen of the Jury," said he, "the remarks of my friend Lawborn about ugly men, comes home to my bosom like the sweet oders of a rose to its neighboring great sister, the cabbage. It was a grateful, a just tribute to that neglected class of the community—ugly men, I wish to say something for my client, although it must in candor be admitted, that he had 'gone to pot.' I don't see why we should throw the kettle after him; he may be the victim of circumstances; he looks very bashful now, and it may be the girls scared him; who knows? At least I claim for him the benefit of a doubt.

"Why, gentlemen, many of us have, or might have suffered from a concatenation of circumstances as strong as that under which my client labors. Let me relate a little personal anecdote in illustration. When I was making the secret canvass of this country, with my friend Cartwright, the Pioneer Preacher, we chanced to stop at the house of one of our old Kentucky farmers, whose log-cabin parlor, kitchen and hall were blended in one, and only separated at night by sundry blankets hung up between the beds. As we were candidates for the august Legislature of Illinois, our host treated us with the privacy of a blanket room. During the night I was awakened by some one throwing their leg over me with some force. I thought it was neighbor Cartright, and took hold of it to give it a toss back; but it didn't feel like one of his white oak legs, and while I was feeling it to ascertain the correctness of my half-awake doubts, a stifled scream thoroughly awakened me, and the leg was withdrawn. Why, gentlemen, would you believe me? It was the leg of our host's daughter! Imagine my position if you can! What an apparent breach of hospitality! While I was imagining an excuse for my conduct, the 'old folks' struck a light, and the blanket between our bed and that of the buxom damsel, was discovered to have been pulled down! More damning proof, thought I. I feigned sleep, but kept one corner of my left eye open for observation. The blanket was soon fixed up, and I was greatly relieved to hear the damsel explain to her mother that she herself had invaded our bed while dreaming, caused by some un-digestable vegetables she had eaten for her supper. Our host was serene and affable in the morning, and I had no need to apologize; but, gentlemen, imagine what an escape I had, and have mercy on my client."

Uncle Abe made a side splitting speech all through, and Douglas followed with a "constitutional" argument.

The Jury returned a verdict of "guilty of scaring the girls," and the Judge sentenced the culprit to be whipped in the back yard, by the girls he had scared.

Dr. Wallace, the acting Sheriff, (no, a paymaster in the army,) went out and bought a cow hide, and the fellow was soon tied up to a post, and the girls made per force to give him thirty-nine well laid on.

The whole affair was a rich evening's divertisement, and cost nothing more than a few lost vest buttons and strained button holes.

It is needless to say that the fellow became a non est man from that day thenceforth.

Most of the readers of this have perhaps read a good story of Oliver Ditson, the celebrated Boston Music publisher. After he had been in business several years, his New Hampshire friends invited him to open his Thanksgiving in his native town, he accepted the invitation and started with some of his friends. On the way Ditson was the great man of the occasion, and was therefore placed at the head of the table, when it devolved upon him to ask the blessing. Now Oliver practiced more religion than he knew the exact forms for, and he was in a sad dilemma; but he essayed boldly the task. He thanked God for all the 'creature comforts' there were upon the table—for all there ever had been—for all that was expected. But how to quit? He went on, thanking and trying to think at the same time how 'blessings' ended, but to no purpose. Knives rattled, plates moved, and Oliver saw the hungry people were getting impatient, and he came to the end in a real business like style, with—"Yours, respectfully, OLIVER DITSON."

Almost as good an anecdote is told by Uncle Abe of one of his old friends, a Mr. Sawyer, who merchandized either in Macon or Champaign County. Sawyer, was a Yankee, and distinguished for little besides an immoderate liking for "sassingers," as he called that "linked sweetness" which polite people call sausages. When Uncle Abe was stumping the Sangamon District for Congress, it befell that he and Sawyer met at the same country hotel, which was kept by a hardshell Baptist, whose foible was long prayers and blessings at table. They—Lincoln and Sawyer—happened to be going to the same town by the same coaches. So they were up betimes and ready, but breakfast was delayed. They at last got to the table, and the Deacon was just closing his eyes preliminary to the blessing, when the stage horn blew.

"Bless me, Deacon, there's the stage ready," cried the Sawyer; "thank God for the sassengers, and let us fall too."

I hardly need say the Deacon's blessing—and perhaps his breakfast were spoiled. But Sawyer had his "sassengers."

When the present State House of Illinois, was being built—and it's a passable edifice, baring it is too low in the ground, and the summer house up on its top is too low to catch the cool breezes—it chanced that among the workmen engaged upon it was a New Yorker named Johnson. This man had a sovereign contempt for most of the shinplasters then circulating in Illinois; nor was he much amiss in this, for if it was now in existence, it would be exchangable at par with Jeff Davis' shinplasters. But through the instrumentality of Col. Thornton's negotiations in New York with McAlister of Stebbins, (a claim, by the way, that has never been settled but came near settling the State a la Mattoon,) a large amount of the bills of the New York Metropolitan Bank were put into circulation about Springfield. For this currency Johnson conceived so great a partiality that the passion of avarice soon turned it into a mania. He bought all these notes his means permitted, and stored them away about his person with miserly care.

One Sunday Johnson was invited to ride out to the Cut off by a man (Smith for the nonce) and accepted. They did'nt stop at the Cut-off, but went direct to Sangamon River. Here, they were overheard quarrelling.

Smith came home without Johnson, who was soon missed, and as he was known to have gone away with Smith, that individual was soon put in that log building still standing (it did in '62) back of Carrigan's Hotel, and which has since served as a hen house etc. (Why don't Butler take a picture of it, to show the "rising generation" what a small house used to hold all the known or taken rogues of old Sangamon?)

The examination of Smith, did not take place until the river bank had been examined. There were signs of a struggle on the bank, and to the water's edge, which gave force to the evidence of the man who heard them in dispute, and all felt convinced that Johnson had been murdered. Although a careful examination and dredging of the river failed to produce the body, Smith was committed for trial.

Uncle Abe was engaged as counsel for Johnson, but had little hopes of being of any earthly aid to him.

At last the day of trial came, and the prisoner plead "not guilty."

I think it was Melborn who was the prosecuting Attorney; before the prosecution had opened the case Uncle Abe rose and said:

"May it please the Court, I have a motion to make before the prosecution opens; and as it may save the Court some unnecessary labor, I hope it will be entertained. I move that the indictment be quashed and the prisoner discharged!"

The astonishment of the crowded Court room was immense, shared alike by Judge, bar and spectators. As soon as the Judge recovered his equanimity he asked:

"Upon what grounds is so extraordinary a motion made?"

"Why the man Johnson, was not murdered at all, and I have the pleasure of introducing him to the presence of the Court."

Johnson was led forward. Hundreds recognized him immediately, The excitement was so great that the Judge adjourned the Court.

It seems that the parties had quarreled, Johnson had been pushed into the river, but had got out and wandered off in a state of partial aberation of mind and had been working on a farm. His passion for Metropolitan Bank Notes and his name suggested an idea that he was the missing man, and he was opportunely produced in time to save a man from being hung.

One of the best natured fellows in the world, when he is not mad, is Joe Reed, of Logan County, Illinois, Joe is a staunch Republican—a real rip-rarer in the cause, and has given Uncle Abe the lift of a mighty broad pair of shoulders more than once, although at first he had a poor opinion of the rail-splitter. Thereby hangs a tale.

In 18—, (the date is forgotten on account of the coldness of the weather that winter,) Joe lost a couple of mules. After they had been gone for a long time, he chanced to hear of them in a settlement somewhere within the present bounds of Macon County. Illinois. At the first opportunity Joe started on a mule hunt, determined to find either the mules or some trace of them. On reaching the neighborhood in question, Joe was satisfied that an old fellow named Bosby Sheel, had his mules; and when he went in person, and saw them, the assurance of his eyes made "assurance double sure." He at once made claim, but the old fellow had heard that possession was nine points of the law—he declined to surrender them; Joe immediately appealed to old Squire P———, who at once summoned the holder of the mules to his Court. The Squire informed Joe that he would have to prove property; but Joe said he would only have to swear to his property. In this dilemma, the Squire adjourned Court till after dinner and remarked to Joe that he had better get a lawyer.

"There is young Abe Lincoln, he don't live far from here, and he'll be at my house after dinner."

As he was the only lawyer immediately thereabouts, Joe thought he had best employ him, in order to "have the law on his side."

Soon after dinner a stranger arrived, and the Justice (who was landlord of the only hotel in the settlement,) whispered to Joe, that that was the lawyer.

"What!" exclaimed Joe, "that lean, lank gawky? Why, I'll bet both of them mules I know more law nor he does, for I'm a 'Squire at home myself—I am."

"But his looks is mighty deceivin', I tell you," said Boniface. "He's gin out to be one of the piertest young fellows short o' Sangamon."

But Joe was decided, and the 'Squire re-convened his Court, he having the meantime laid the case before his young friend, the lawyer, and got his opinion.

Acting his own lawyer, Joe felt it due to his course to give a concise statement of the law. As he stood up, he still continued to read from a green-covered book that had engaged his attention most of the day It was one of Cooper's latest novels. As Joe gave his version of the law, it seemed to 'Squire P——— that he was reading the law.

"Is that really the law?" said he, as Joe finished his version of the law—not the book. "Let me see that book."

Joe mechanically handed it to him.

After pouring over it for some time, he handed it back, with an air of disappointment, remarking:

"Drat me! if I see any sich law in that book."

"Well, it ain't no wonder ye don't—that's the Red Rover, a novel and not a law book, and you've been and lost my place too," Joe found his place, and continued: "what I told you is what the law says, and I know it's so."

"Well, as you're a 'Squire, too, I reckon you ought to know. As the mules don't belong to old man Bosby Sheel and you swear they are you'rn, I hold he's bound to give'em up."

Joe rallied the old Squire rather hard about looking over the Red Rover for extra law, but finally "give a treat" and left the Squire and his friend in the best of humors.

Said Uncle Abe when he had the small-pox, "I now can give something to every one who calls."

Judge Baldwin, an old and highly respectable and sedate gentleman, called a few days since on Gen. Halleck, and presuming upon a familiar acquaintance in California formerly, solicited a pass outside of our lines, to see a brother in Virginia, not thinking that he would be met with a refusal, as both his brother and himself were good Union men.

"We have been deceived too often," said General Halleck, "and I regret I can't grant it."

Judge B. then went to Stanton, and was very briefly disposed of with the same result. Finally he obtained an interview with Uncle Abe, and stated his case.

"Have you applied to Gen. Halleck?" inquired the President.

"And met with a flat refusal," said Judge B.

"Then you must see Stanton," continued Uncle Abe.

"I have, and with the same result," was the reply.

"Well, then," said Uncle Abe, with a smile of good humor, "I can do nothing; for you must know that I have very little influence with this Administration."

The following incident, which occurred at the White House, will appeal to every heart. It reveals unmistakably the deep kindness of Uncle Abe's character:

"At a reception recently at the White House, many persons present noticed three little girls poorly dressed, the children of some mechanic or laboring man, who had followed the visitors into the house to gratify their curiosity. They were passed from room to room, and were passing through the reception room with some trepidation, when Uncle Abe, called to them: 'Little girls, are you going to pass me without shaking hands?' Then he bent his tall, awkward form down, and shook each little girl warmly by the hand. Everybody in the apartment was spellbound by the incident, so simple in itself, yet revealing so much of Uncle Abe's character."

During the canvass between Uncle Abe, and Peter Cartright, the celebrated Pioneer Preacher, it chanced that Cartright, was returning to his home from the Williamsville and Wiggins Lane settlement. The nearest crossing of the Sangamon was at Carpenter's Mills, where there was the convenience of a ferry instead of a bridge, as is now the case. Upon the hill on the western side of the river, Cartright saw a man elevated upon a barrel in front of a little grocery—and on nearing him, he discovered that he was giving the Democrats in general, and Uncle Peter Cartright in particular, a perfect fusilade of small shots of slang and abuse.

"I tell you, boys, I'm a Whig,—a real Harrison Tippacanoe and Tyler too, Whig," said he. "I'm for putting down all these cuss'd locofocos, and if we can't vote'em down, why I go for lickin'em' down. There's long Abe Lincoln that's runnin' for the Legislature—he's the chap to vote for. He's one of the people—split rails and got his edycation by moonlight. He don't go round the country prayin' and preachin' like that mean Methodist cuss, Peter Cartright, that's runnin' agin him. I'd like to know what we wants of a parson to make laws for us? Just elect him, and fust you know he'll have a bill into the Legislature, to fine us for not goin' to meetin' or for drinkin' a glass of whisky. I'll tell you what, if he ever comes round here, I'll just pass him inter the Sangamon—certain—sure."

Just here Uncle Peter Cartright enquired for "the ferryman.

"I'm the ferry-man, old hoss," sung out the rustic orator, "and ken put ye cross the river in no time." Uncle Peter signified his desire to cross, and the twain started towards the ferry boat. The Preacher stepping into the boat, hitched his horse to the side, while the ferryman shoved out into the stream.

"So you are a Lincoln man?" queried Uncle Peter. "I'm that hoss."

"And so I presume you would douse a Cartright man if you had a chance?"

"I mought do it stranger."

"Certainly you would douse Mr. Cartright?"

"Sure's winkin', old fellow."

"Well Sir, I am Peter Cartright at your service," and before the ferryman recovered from his surprise Uncle Peter pitched him into the river, took the pole and put himself across the river.

The ferryman did'nt vote for Uncle Peter but he altered his opinion of Methodist preachers in general and Uncle Peter in particular.

One day as Uncle Abe, and a friend were sitting on the House of Representatives steps, the session closed, and the members filed out in a body. Uncle Abe looked after them with a serious smile. "That reminds me," said he, "of a little incident when I was a boy; my flat boat lay up at Alton on the Mississippi, for a day, and I strolled about the town. I saw a large stone building, with massive stone walls, not so handsome though, as this, and while I was looking at it, the iron gateway opened, and a great body of men came out. 'What do you call that?' I asked a bystander. 'That,' said he, 'is the State Prison, and those are all thieves going home. Their time is up.'"

Uncle Abe was terribly bored by the office seekers, even before the Presidential house-warming had scarcely began. The Illinois politicians were the most ravenous pap-Suckers of all.

"Just wait a little," said Uncle Abe, "I can assure you, as L———d S———t did the swine, 'there's enough for all.'"

"Let us have the story, Uncle Abe," said one of the crowd, who evidently expected something rich.

"Why, you see," began Uncle Abe, "I attended court many years ago at Mt. Pulaski, the first county seat of Logan County, and there was the jolliest set of rollicking young Lawyers there that you ever saw together. There was Bill F———n, Bill H———n, L———d S———t, and a lot more, and they mixed law and Latin, water and whisky, with equal success. It so fell out that the whisky seemed to be possessed of the very spirit of Jonah. At any rate, S———t went out to the hog-pen, and, leaning over, began to 'throw up Jonah.' The hogs evidently thought it feed time, for they rushed forward and began to squabble over the voided matter.

"'Don't fight (hic),' said S———t: 'there's enough (hic) for all.'"

—The politicians couldn't see anything to laugh at, although the "snubbin" was plain enough.

Uncle Abe, in elucidating his estimate of Presidential honors, tells a clever story, as he always does, when he sets about it. It seems that Windy Billy, who is a politician of no ordinary pretensions, was a candidate for the Consulship of Bayonne, and he urged his appointment with the eloquence of a Clay or a Seward. He boasted vociferously of his activity in promoting the success of the Republican ticket, and averred with his impassioned earnestness that he and he alone had made Uncle Abe President.

"Ah!" exclaimed Uncle Abe, "and it was you who made me President, was it?" a twinkle in his eye all the time.

"Yes," said Billy, rubbing his hands and throwing out his chest, as a baggage-master would a small valise, "yes, I think I may say I am the man who made you President."

"Well, Billy, my boy, if that's the case, it's a h—ll of a muss you got me into, that's all."

A prominent Senator was remonstrating with Uncle Abe a few days ago about keeping Mr. Chase in his Cabinet, when it was as well known that Mr. C. is opposed, tooth and nail, to Uncle Abe's re-election.

"Now, see here," said Uncle Abe, "when I was elected I resolved to hire my four Presidential rivals, pay them their wages and be their 'boss.' These were Seward, Chase, Cameron and Bates; but I got rid of Cameron after he had played himself out. As to discharging Chase or Seward, don't talk of it. I pay them their wages and am their boss, and would'nt let either of them out on the loose for the fee simple of the Almaden patent."

Some of the farmers in and about Saggamon county, Illinois, have been and still are so intent on cattle-raising, that the business is a sort of cattle-mania. Uncle Peter was one Sunday preaching near a good old deacon of this sort, whose piety was somewhat like that of a card-playing lady mentioned by Addison, (Spectator No. 7,) who had a set hour for her devotions, and if she happened to be at a game, would get a friend to "hold her hand" while she said her prayers. Our worthy deacon was rather vain of his "gift" praying and saying "blessings" at table. As a matter of courtesy, he might occasionally ask a visiting preacher to pray or ask a blessing; but he never failed to exhibit his "gift" to his visitors. He had a singsong way of "getting it off," at the same time beating time with his hands on either side of his plate. On the occasion alluded to, he began—"Oh Lord! (thump) bless the creature comforts (thump) provided for our (thump) sustenance (thump.) Bless it (thump) to our needs (thump) and necessities, (thump). Lead us aright, (thump) but if we stray (thump) put us back (thump) into the right path, (thump). Bless the stranger (thump) that comes beneath our roof, (thump) and keep his feet (thump) in pleasant paths, (thump). What we ask (thump) amiss, (thump) withhold; (thump) but grant us what our (thump) short-sightedness omits, (thump) and thine be the glory (thump) now and for ever, (thump) a———."

And here the old deacon stopped suddenly, opened his eyes, and looking across the table, asked:

"Son John, did Mr. Jones settle yet for that Durham cow?"

"Yes, father—it's all right."

"Amen," concluded the deacon.

"Cattle! cattle!" exclaimed Uncle Peter in ill-concealed disgust.

"Why, you can't say your prayers without having cattle running through your head; I wonder the Lord don't turn such Christians into cattle!"

When Uncle Abe was making a plea in one of the county Circuit Courts, not far from Springfield, one of the lawyers becoming sensible that he was being out-generaled, remarked to Uncle Abe, as he sat down—

"I smell a mice."

"Why don't you quote Shakspeare correctly?" said Uncle Abe.

"Why," said the other, "I was not aware that I Was quoting Shakspeare at all."

"Certainly you were, and had you done it properly, it would have been more expressive and less vulgar. The correct expression is, 'I smell a device.'"

In the Black Hawk war, Uncle Abe belonged to a militia company in the service. On a scout, the company encountered the Indians, and in a brisk skirmish drove them some miles, when, night coming on, our forces encamped. Great was the consternation on discovering that Lincoln was missing. His absence or rather his stories, from the bivouac, was a misfortune. Suddenly, however, he came into camp. "Maj. Abe, is that you? Thought you were killed. Where've you been?" were the startling speculations. "Yes," said Uncle Abe, "this is me—ain't killed either."

"But where have you been all the time?"

"Oh, just over there."

"But what were you over there for? Didn't run away, did you?"

"No," said he deliberately, "I don't think I run away; but, after all, I reckon if anybody had seen me going, and had been told I was going for a doctor, he would have thought somebody was almighty sick."

So thick had the rats become in Logan County, a few years ago, that the means of getting rid of the nuisance was freely discussed. The newly organized Agricultural Society, finally concluded to offer three premiums for the then largest numbers. The man who took the largest prize, exhibited over 1,700 scalps all caught in the space of three weeks. At the time these prizes were pending, Uncle Abe attended Court there, and Col. L———n, (a considerable gourmand,) by the way, was discussing the best way to get rid of the rats, and finally asked Uncle Abe's opinion.

"Why," said Uncle Abe, "rats are a 'cunning cattle,' and soon find out how things are going. I introduce them to your table as a delicacy, and when they find out you are making 'game' of them they will soon give you a wide berth."

The Colonel winced under a faint impression; but silently ratified Uncle Abe's conclusions. "Yes," chimed in M———, "we might go so far as to use their pelts to ornament our winter clothing."

On a late occasion, when the White House was open to the public, a farmer from one of the border counties of Virginia told Uncle Abe that the Union soldiers, in passing his farm, had helped themselves not only to hay, but his horses, and he hoped the President would urge the proper officer to consider his claim immediately. "Why, my dear sir," replied Uncle Abe, blandly, "I couldn't think of such a thing. If I considered individual cases, I should find work for twenty Presidents!" Bowie urged his needs persistently; Uncle Abe declined good-naturedly. "But," said the persevering sufferer, "couldn't you just give me a line to Colonel ———- about it? just one line?" "Ha, ha, ha!" responded amiable Uncle Abe, shaking himself fervently, and crossing his legs the other way, "that reminds me of old Jack Chase out in Illinois." At this the crowd huddled forward to listen. "You have seen Jack—I knew him like a brother—used to be a lumberman on the Illinois, and he was steady and sober, and the best raftsman on the river. It was quite a trick twenty-five years ago to take the logs over the rapids, but he was skillful, with a raft, and always kept her straight in the channel. Finally a steamboat was put on, and Jack—he's dead now, poor fellow!—was made captain of her. He used to take the wheel going through the rapids. One day, when the boat was plunging and wallowing along the boiling current, and Jack's utmost vigilance was exercised to keep her in the narrow channel, a boy pulled his coat tail, and hailed him with, 'Sir, Mister Captain! I wish you'd just stop your boat a minute—I've lost my apple overboard!'"

A committee, just previous to the fall of Vicksburg, solicitous for the morale of our armies, took it upon themselves to visit the President and urge the removal of General Grant. .

"What for?" asked Uncle Abe.

"Why," replied the busy-bodies, "he drinks too much whisky."