Project Gutenberg's The Book of Fables and Folk Stories, by Horace E. Scudder This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Book of Fables and Folk Stories Author: Horace E. Scudder Release Date: April 14, 2014 [EBook #45384] Last Updated: November 19, 2016 Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BOOK OF FABLES *** Produced by David Widger from page images generously provided by the Internet Archive

CONTENTS

THE BOOK OF FABLES AND FOLK STORIES

THE GOOSE THAT LAID GOLDEN EGGS

LITTLE ONE EYE, LITTLE TWO EYES, AND LITTLE THREE EYES

A COUNTRY FELLOW AND THE RIVER

THE SPENDTHRIFT AND THE SWALLOW

THE MILLER, HIS SON, AND THEIR ASS

CINDERELLA, OR THE GLASS SLIPPER

THE COUNTRY MOUSE AND THE TOWN MOUSE

THE SLEEPING BEAUTY IN THE WOOD

THE CAT, THE MONKEY, AND THE CHESTNUTS

THE FLIES AND THE POT OF HONEY

THE LION, THE ASS, AND THE FOX

THE COUNTRY MAID AND HER MILK-PAIL

THE CAT, THE WEASEL, AND THE YOUNG RABBIT

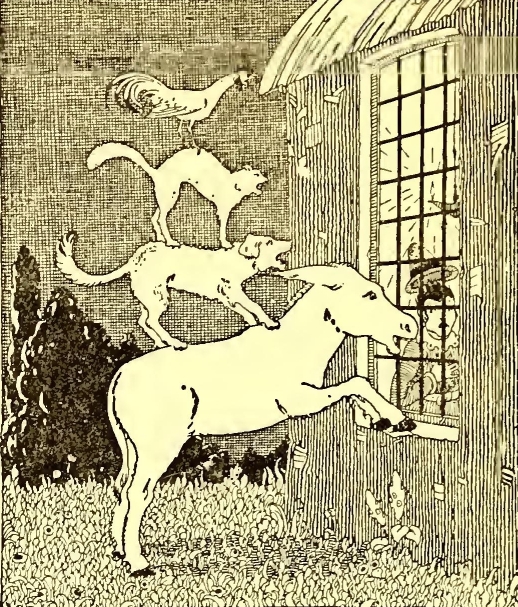

For more than a generation Mr. Scudder’s Book of Fables and Folk Stories has been a prime favorite with young readers. It has seemed to the publishers that a book which has maintained its popularity so long might well be furnished with illustrations more in accordance with the taste of the present day than those which were originally used. All the old pictures have therefore been replaced by drawings made by a modern artist, and it is hoped that readers of the volume will find its old charm heightened by this new feature.

4 Park St., Boston October, 1919

Once upon a time there lived in a certain village a little girl. Her mother was very fond of her, and her grandmother loved her even more. This good old woman made for her a red cloak, which suited the child so well that ever after she was called Little Red-Riding-Hood. One day her mother made some cakes, and said to Little Red-Riding-Hood:—

“Go, my dear, and see how grandmother does, for I hear that she has been very ill. Carry her a cake and a little pot of butter.”

Little Red-Riding-Hood set out at once to go to her grandmother, who lived in another village. As she was going through the wood she met a large Wolf. He had a very great mind to eat her up; but he dared not, for there were some wood-choppers near by. So he asked her:—

“Where are you going, little girl?” The poor child did not know that it was dangerous to stop and talk with the Wolf, and she said:—

“I am going to see my grandmother, and carry her a cake and a little pot of butter from my mother.”

“Does she live far off?” asked the Wolf.

“Oh, yes. It is beyond that mill, at the first house in the village.”

“Well,” said the Wolf, “I will go and see her, too. I will go this way; do you go that, and we will see who will be there soonest.”

At this the Wolf began to run as fast as he could, taking the nearest way, and Little Red-Riding-Hood went by the farthest. She stopped often to chase a butterfly, or pluck a flower, and so she was a good while on the way. The Wolf was soon at the old woman’s house, and knocked at the door—tap, tap!

“Who is there?”

“Your grandchild, Little Red-Riding-Hood,” replied the Wolf, changing his voice. “I have brought you a cake and a pot of butter from mother.” The good grandmother, who was ill in bed, called out:—

“Pull the string, and the latch will go up.” The Wolf pulled the string, and the latch went up. The door opened, and he jumped in, and fell upon the old woman, and ate her up in less than no time, for he had not tasted food for three days. He then shut the door, and got into the grandmother’s bed. By and by, Little Red-Riding-Hood came and knocked at the door—tap, tap!

“Who is there?”

Little Red-Riding-Hood heard the big voice of the Wolf, and at first she was afraid. Then she thought her grandmother must have a bad cold, so she answered:—

“Little Red-Riding-Hood. I have brought you a cake and a pot of butter from mother.” The Wolf softened his voice as much as he could, and called out:—

“Pull the string, and the latch will go up.” Little Red-Riding-Hood pulled the string, and the latch went up, and the door opened. The Wolf was hiding under the bedclothes and called out in a muffled voice:—

“Put the cake and the pot of butter on the shelf, and come to bed.”

Little Red-Riding-Hood made ready for bed. Then she looked with wonder at her grandmother, who had changed so much, and she said:—“Grandmother, what great arms you have!”

“The better to hug you, my dear.”

“Grandmother, what great ears you have!”

“The better to hear you, my dear.”

“Grandmother, what great eyes you have!”

“The better to see you, my dear.”

“Grandmother, what great teeth you have!”

“The better to eat you.”

And at this the wicked Wolf sprang up and fell upon poor Little Red-Riding-Hood and ate her all up.

There was a man who once had a Goose that always laid golden eggs, one every day in the year.

Now, he thought there must be gold inside of her. So he wrung her neck and laid her open.

He found that she was exactly like all other geese. He thought to find riches, and lost the little he had.

This fable teaches that one should be content with what one has, and not be greedy.

A Dog once made his bed in a manger. He could not eat the grain there, and he would not let the Ox eat it, who could.

A hungry Fox found some bunches of grapes upon a vine high up a tree. He tried to get at them, but could not. So he left them hanging there and went off, saying to himself:—

“They are sour grapes.”

That is what people sometimes do when they cannot get what they want—they make believe that what they want is good for nothing.

There was once a woman who had three daughters. The eldest was called Little One Eye, because she had only one eye in the middle of her forehead. The second was called Little Two Eyes, because she had two eyes like other people. The youngest was called Little Three Eyes, because she had three eyes; the third eye was in the middle of her forehead.

Because Little Two Eyes looked like other people, her sisters and her mother could not bear her. They said:—

“You have two eyes and are no better than anybody else. You do not belong to us.” They knocked her about, and gave her shabby clothes, and fed her with food left over from their meals.

One day Little Two Eyes was sent into the fields to look after the goat. She was hungry, because her sisters had given her so little to eat, and she sat down and began to cry. She cried so hard that a little stream of tears ran out of each eye. All at once a wise woman stood near her, and asked:—

“Little Two Eyes, why do you cry?” Little Two Eyes said:—

“Have I not need to cry? Because I have two eyes, like other people, my sisters and my mother cannot bear me. They knock me about and they give me shabby clothes. They feed me only with the food left over from their table. To-day they have given me so little that I am very hungry.”

The wise woman said:—

“Little Two Eyes, dry your eyes, and I will tell you what to do. Only say to your goat: ‘Little goat, bleat; little table, rise,’ and a table will stand before you, covered with food. Eat as much as you like. When you have had all you want, only say: ‘Little goat, bleat; little table, away,’ and it will be gone.” Then the wise woman disappeared. Little Two Eyes thought: “I must try at once, for I am too hungry to wait.” So she said:—

“Little goat, bleat; little table, rise,” and there stood before her a little table covered with a white cloth. On it were laid a plate, knife and fork, and silver spoon. The nicest food was on the plate, smoking hot. Then Little Two Eyes began to eat, and found the food very good. When she had had enough, she said:—

“Little goat, bleat; little table, away.” In an instant the table was gone.

“That is a fine way to keep house,” thought Little Two Eyes.

At the end of the day Little Two Eyes drove her goat home. She found a dish with some food in it. Her sisters had put it aside for her, but she did not taste it. She did not need it.

The next day she went out again with her goat, and did not take the few crusts which her sisters put aside for her. This went on for several days. At last her sisters said to each other:—

“All is not right with Little Two Eyes. She always leaves her food. She used to eat all that was given her. She must have found some other way to be fed.”

They meant to find out what Little Two Eyes did. So the next time that Little Two Eyes set out, Little One Eye came to her and said:—

“I will go with you into the field, and see that the goat is well taken care of, and feeds in the best pasture.” But Little Two Eyes saw what Little One Eye had in her mind. So she drove the goat into the long grass, and said:—

“Come, Little One Eye, we will sit down and I will sing to you.” Little One Eye sat down. She was tired after her long walk in the hot sun, and Little Two Eyes began to sing:—

“Are you awake, Little One Eye? Are you asleep, Little One Eye? Are you awake, Little One Eye? Are you asleep, Little One Eye? Are you awake? Are you asleep? Awake? Asleep?” By this time Little One Eye had shut her one eye and was fast asleep. When Little Two Eyes saw this, she said softly:—

“Little goat, bleat; little table, rise;” and she sat at the table and ate and drank till she had had enough. Then she said as before:—

“Little goat, bleat; little table, away,” and in a twinkling all was gone.

Little Two Eyes now awoke Little One Eye, and said:—

“Little One Eye, why do you not watch? You have been asleep, and the goat could have run all over the world. Come! let us go home.” So home they went, and Little Two Eyes again did not touch the dish. The others asked Little One Eye what Little Two Eyes did in the field. But she could only say:—

“Oh, I fell asleep out there.”

The next day, the mother said to Little Three Eyes:—

“This time you must go with Little Two Eyes, and see if any one brings her food and drink.” Then Little Three Eyes said to Little Two Eyes:

“I will go with you into the field, and see that the goat is well taken care of, and feeds in the best pasture.” But Little Two Eyes saw what Little Three Eyes had in her mind. So she drove the goat into the long grass, and said:—“Come, Little Three Eyes, we will sit down, and I will sing to you.” Little Three Eyes sat down. She was tired after her long walk in the hot sun, and Little Two Eyes began to sing, as before:—

“Are you awake, Little Three Eyes?” but instead of going on,—

“Are you asleep, Little Three Eyes?” she did not think, and sang:—

“Are you asleep, Little Two Eyes?” and went on:—

“Are you awake, Little Three Eyes? Are you asleep, Little Two Eyes? Are you awake? Are you asleep? Awake? Asleep?” By this time the two eyes of Little Three Eyes fell asleep. But the third eye did not go to sleep, for it was not spoken to by the verse. Little Three Eyes, to be sure, shut it, and made believe that it went to sleep. Then she opened it a little way and watched Little Two Eyes.

When Little Two Eyes thought Little Three Eyes was fast asleep, she said softly:—

“Little goat, bleat; little table, rise;” and she sat at the table and ate and drank till she had had enough. Then she said as before:—

“Little goat, bleat; little table, away.” But Little Three Eyes had seen everything. Little Two Eyes now woke Little Three Eyes, and said:—

“Little Three Eyes, why do you not watch? You have been asleep, and the goat could have run all over the world. Come! let us go home.”

So home they went, and Little Two Eyes again did not touch the dish. Then Little Three Eyes said to the mother:—

“I know why the proud thing does not eat. She says to the goat: ‘Little goat, bleat; little table, rise,’ and there stands a table before her. It is covered with the very best of things to eat, much better than anything we have. When she has had enough to eat, she says: ‘Little goat, bleat; little table, away,’ and all is gone. I have seen it just as it is. She put two of my eyes to sleep, but the one in my forehead stayed awake.” Then the mother cried out:—

“Shall she be better off than we are?” With that she took a knife and killed the goat. Poor Little Two Eyes went to the field, and sat down and began to cry. All at once the wise woman stood near her, and asked:—

“Little Two Eyes, why do you cry?” Little Two Eyes said:—

“Have I not need to cry? My mother has killed the goat. Now I must suffer hunger and thirst again.” The wise woman said:—

“Little Two Eyes, dry your eyes, and I will tell you what to do. Beg your sisters to give you the heart of the goat. Then bury it in the ground before the door of the house. All will go well with you.” Then the wise woman was gone, and Little Two Eyes went home and said to her sisters:—

“Sisters, give me some part of my goat. I do not ask for anything but the heart.” They laughed, and said:—

“You can have that, if you do not want anything else.”

Little Two Eyes took the heart and buried it in the ground before the door of the house.

Next morning the sisters woke and saw a splendid tree in front of the house. It had leaves of silver and fruit of gold. It was wonderful to behold; and they could not think how the tree had come there in the night. Only Little Two Eyes knew that the tree had grown out of the heart of the goat. Then the mother said to Little One Eye:—

“Climb up, my child, and pluck some fruit from the tree.” Little One Eye climbed the tree. She put out her hand to take a golden apple, but the branch sprang back. This took place every time. Try as hard as she could, she could not get a single apple. Then the mother said:—

“Little Three Eyes, you climb up. You can see better with your three eyes than Little One Eye can.” Down came Little One Eye, and Little Three Eyes climbed the tree. She put out her hand, and the branch sprang back as it had from Little One Eye. At last the mother tried, but it was the same with her. She could not get a single apple. Then Little Two Eyes said:—

“Let me try.”

“You!” they all cried. “You, with your two eyes like other people! What can you do?” But Little Two Eyes climbed the tree, and the branch did not spring back. The golden apples dropped into her hands, and she brought down her apron full of them. Her mother took them away from her, and her two sisters were angry because they had failed, and they were more cruel than ever to Little Two Eyes.

While they stood by the tree, the Prince came riding near on a fine horse.

“Quick, Little Two Eyes,” said her sisters, “creep under this cask; we are ashamed of you.” And they threw an empty cask over her, and pushed the golden apples under it.

The Prince rode up and gazed at the splendid tree. “Is this splendid tree yours?” he asked of the sisters. “If you will give me a branch from it, I will give you anything you wish.” Then Little One Eye and Little Three Eyes said the tree was theirs, and they would break off a branch for him. They put out their hands, but again the branches sprang back. Then the Prince said:—

“This is very strange. The tree is yours, and yet you cannot pluck the fruit.”

They kept on saying that the tree was theirs, but while they were saying this, Little Two Eyes rolled a few of the apples out from under the cask. The Prince saw them, and asked:—

“Why! where did these golden apples come from? Who is under the cask?” Little One Eye and Little Three Eyes told the Prince that they had a sister.

“But she does not show herself,” they said. “She is just like other people. She has two eyes.” Then the Prince called:—

“Little Two Eyes! come out!” So Little Two Eyes was very glad and crept out from under the cask.

“Can you get me a branch from the tree?”

“Yes,” said Little Two Eyes, “I can, for the tree is mine.” Then she climbed the tree and broke off a branch. It had silver leaves and golden fruit, and she gave it to the Prince. Then the Prince said:—

“Little Two Eyes, what shall I give you for it?”

“Oh,” said Little Two Eyes, “I suffer hunger and thirst all day long. If you would take me with you, I should be happy.”

So the Prince lifted Little Two Eyes upon his horse, and they rode away. He took her to his father’s house and made her Princess, and she had plenty to eat and drink and good clothes to wear. Best of all, the Prince loved her, and she had no more hard knocks and cross words.

Now, when Little Two Eyes rode away with the Prince, the sisters said:—

“Well, we shall have the tree. We may not pluck the fruit, but every one will stop to see it and come to us and praise it.” But the next morning when they went to look at the tree, it was gone.

Little Two Eyes lived long and happily. One day, two poor women came to her, and asked for something to eat. Little Two Eyes looked at their faces and knew them. They were Little One Eye and Little Three Eyes. They were so poor that they were begging bread from door to door. Little Two Eyes brought them into the house and was very good to them. Then they both were sorry for the evil they had once done their sister.

T he Wind and the Sun had a dispute as to which of the two was the stronger. They agreed that the one should be called stronger who should first make a man in the road take off his cloak.

The Wind began to blow great guns, but the man only drew his cloak closer about him to keep out the cold. At last the gust was over.

Then the Sun took his turn. He shone and it was warm and bright. The man opened his cloak, threw it back, and at last took it off, and lay down in the shade where it was cool.

So the Sun carried his point against the Wind.

This fable teaches that gentleness often succeeds better than force.

A Crow who was very thirsty found a Pitcher with a little water in it. But the water lay so low that she could not come at it.

She tried first to break the Pitcher, and then to overturn it, but it was too strong and too heavy for her. At last she thought of a way.

She dropped a great many little pebbles into the Pitcher, until she had raised the water so that she could reach it.

A company of Boys were watching some Frogs by the side of a pond, and as fast as any of the Frogs lifted their heads the Boys would pelt them down again with stones.

“Boys,” said one of the Frogs, “you forget that, though this may be fun for you, it is death to us.”

A stupid Boy was sent to market by his Mother to sell butter and cheese. He made a stop by the way at a swift river, and laid himself down on the bank to watch until it should run out.

About midnight, home he went to his Mother, with all his market goods back again.

“Why, how now, my Son?” said she. “What have we here?”

“Why, Mother, yonder is a river that has been running all this day, and I stayed till just now, waiting for it to run out; and there it is, running still.”

“My Son,” said the good woman, “thy head and mine will be laid in the grave many a day before this river has all run by. You will never sell your butter and cheese if you wait for that.”

There was once an old miller, and when he died he left nothing to his three sons except his mill, an ass, and a cat. The eldest son took the mill, the second son took the ass, and so the cat fell to the youngest. This poor fellow looked very sober, and said:—

“What am I to do? My brothers can take care of themselves with a mill and an ass. But I can only eat the cat and sell his skin. Then what will be left? I shall die of hunger.” The cat heard these words and looked up at his master.

“Do not be troubled,” he said. “Give me a bag and get me a pair of boots, and I will soon show you what I can do.”

The young man did not see what the cat could do, but he knew he could do many strange things. He had seen him hang stiff by his hind legs as if he were dead. He had seen him hide himself in the meal tub. Oh, the cat was a wise one! Besides, what else was there for the young man to do?

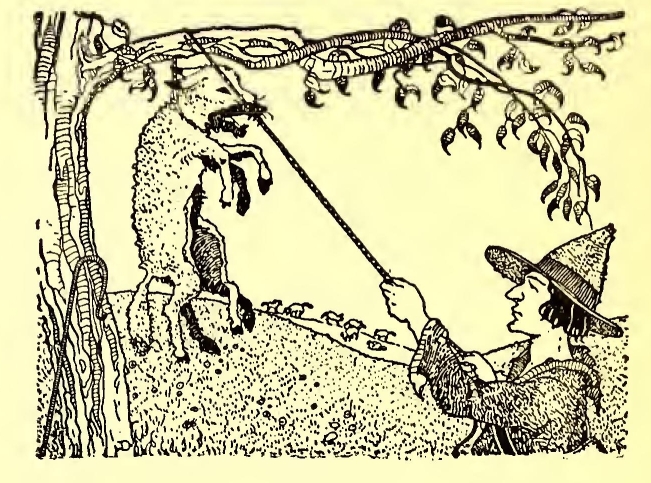

So he got a bag and a pair of boots for the cat. Puss drew on the boots and hung the bag about his neck. Then he took hold of the two strings of the bag with his fore paws and set off for a place where there were some rabbits.

He filled his bag with bran and left the mouth of the bag open. Then he lay down, shut his eyes, and seemed to be sound asleep. Soon a young rabbit smelled the bran and saw the open bag. He went headlong into it, and at once the cat drew the strings and caught the rabbit.

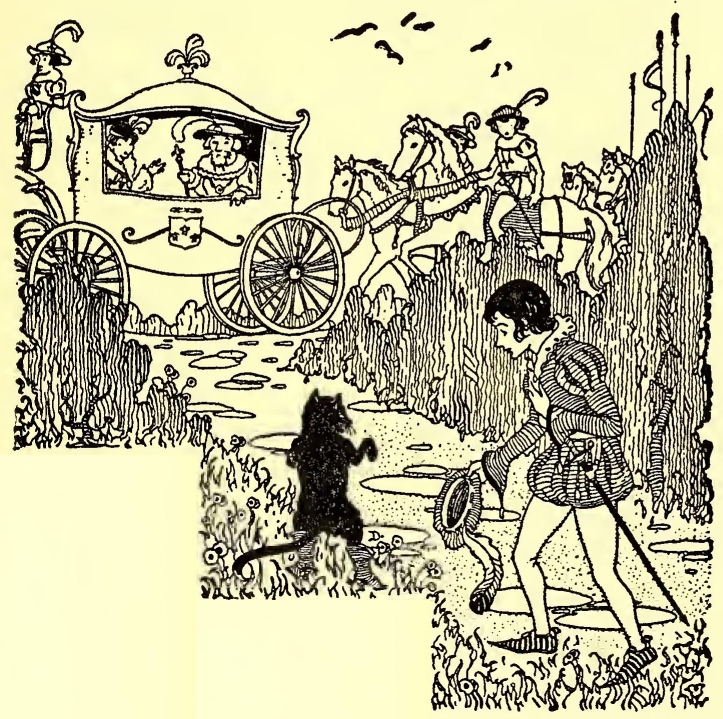

Puss now went to the palace, and asked to speak to the king. So he was brought before the king. He made a low bow and said:—

“Sire, this is a rabbit which my master bade me bring to you.”

“And who is your master?”

“He is the Marquis of Carabas,” said the cat. This was a title which Puss took it into his head to give to his master.

“Tell your master that I accept his gift,” said the king, and Puss went off in his boots. In a few days he hid himself with his bag in a cornfield. This time he caught two partridges, and carried them to the king. The king sent his thanks to the Marquis of Carabas, and made a present to Puss.

So things went on for some time. Every week Puss brought some game to the king, and the king began to think the Marquis of Carabas a famous hunter. Now it chanced that the king and his daughter were about to take a drive along the banks of a river. Puss heard of it and went to his master.

“Master,” said he, “do just as I tell you, and your fortune will be made. You need only go and bathe in the river, and leave the rest to me.”

“Very well,” said his master. He did as the cat told him, but he did not know what it all meant. While he was in the river, the king and the princess drove by. Puss jumped out of the bushes and began to bawl:—

“Help! help! the Marquis of Carabas is drowning! save him!” The king heard and looked out of his carriage. There he saw the cat that had brought him so much game, and he bade his men run to help the Marquis. When he was out of the river, Puss came forward, and told what had happened.

“My master was bathing, and some robbers came and stole his clothes. I ran after them and cried, ‘Stop, thief!’ but they got away. Then my master was carried beyond his depth, and would have drowned, if you had not come by with your men.”

At this the king bade one of his servants ride back and bring a fine suit of clothes for the Marquis, and they all waited. So, at last, the Marquis of Carabas came up to the carriage, dressed much more finely than he ever had been in his life. He was a handsome fellow, and he looked so well that the king at once bade him enter the carriage.

Puss now had things quite to his mind. He ran on before, and came to a meadow, where some men were mowing grass. He stopped before them, and said:—

“The king is coming this way. You must tell him that this field belongs to the Marquis of Carabas, or you shall all be chopped as fine as mince-meat.”

“When the carriage came by, the king put his head out, and said to the men:—

“This is good grass land. Who owns it?”

“The Marquis of Carabas,” they all said, for Puss had thrown them into a great fright.

“You have a fine estate, Marquis,” said the king.

“Yes, Sire,” he replied, tossing his head; “it pays me well.” Puss still ran before the carriage, and came soon to some reapers.

“Tell the king,” he cried, “that all this grain belongs to the Marquis of Carabas, or you shall all be chopped as fine as mince-meat.” The king now came by, and asked the reapers who owned the grain they were cutting.

“The Marquis of Carabas,” they said. So it Went on. Puss bade the men in the fields call the Marquis of Carabas their lord, or it would go hard with them. The king was amazed. The Marquis took it all with a grand air. It was easy to see that he was a very rich and great man. The princess sat in the corner of the carriage, and thought the Marquis no mean fellow.

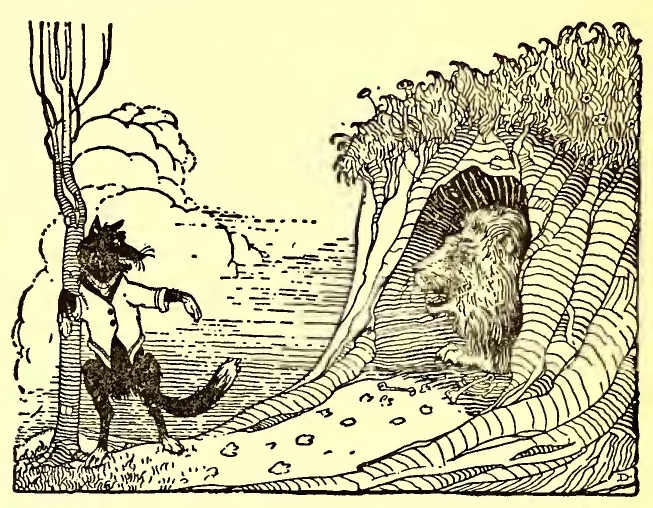

At last they drew near the castle of the one who really owned all the fields they had passed through. Puss asked about him, and found he was a monster who made every one about him very much afraid. Puss sent in word that he should like to pay his respects, and the monster bade him come in.

“I have been told,” said Puss, “that you can change yourself into any kind of animal. They say you can even make yourself a lion.”

“To be sure I can,” said the monster. “Do you not believe it? Look, and you shall see me become a lion at once.” When Puss saw a lion before him he was in a great fright, and got as far away as he could. There he stayed till the lion became a monster again.

“That was dreadful!” said Puss. “I was nearly dead with fear. But it must be much harder to make yourself small. They do say that you can turn into a mouse, but I do not believe it.”

“Not believe it!” cried the monster. “You shall see!” So he made himself at once into a mouse, and began running over the floor. In a twinkling Puss pounced upon him and gave him one shake. That was the end of the monster.

By this time the king had reached the gates of the castle, and thought he would like to see so fine a place. Puss heard the wheels, and ran down just as the king drove up to the door.

“Welcome!” he said, as he stood on the steps of the castle. “Welcome to the castle of the Marquis of Carabas!”

“What! my lord Marquis,” said the king, “does this castle, too, belong to you? I never saw anything so fine. I should really like to enter.”

“Your majesty is welcome!” said the young man, bowing low, taking off the cap which the king had given him. Then he gave his hand to the princess, and they went up the steps. Puss danced before them in his boots.

They came into a great hall, and there they found a feast spread. The monster had asked some friends to dine with him that day, but the news went about that the king was at the castle, and so they dared not go.

The king was amazed at all he saw, and the princess went behind him, just as much pleased. The Marquis of Carabas said little. He held his head high and played with his sword.

When dinner was over, the king took the Marquis one side, and said:—

“You have only to say the word, my lord Marquis, and you shall be the son-in-law of your king.”

So the Marquis married the princess, and Puss in Boots became a great lord, and hunted mice for mere sport, just when he pleased.

A farmer’s Sons once fell out. The Farmer tried to make peace between them, but he could not. Then he bade them bring him some sticks. These he tied together into a bundle, and gave the bundle to each of his Sons in turn, and told him to break it. Each Son tried, but could not.

Then he untied the bundle and gave them each one stick to break. This they did easily, and he said: “So is it with you, my Sons. If you are all of the same mind, your enemies can do you no harm. But if you quarrel, they will easily get the better of you.”

A Lion and a Bear chanced to fall upon a Fawn at the same time, and they began to fight for it. They fought so fiercely that at last they fell down, entirely worn out and almost dead.

A Fox, passing that way, saw them stretched out, and the Fawn dead between them. He stole in slyly, seized the Fawn, and ran away with it for his own dinner. When they saw this, they could not stir, but they cried out:—

“How foolish we were to take all this trouble for the Fox!”

As a Lion lay asleep, a Mouse ran into his mouth. The Lion shut his teeth together and would have eaten him up, but the Mouse begged hard to be let out, saying:—

“If you will let me go, I will repay you some day.”

The Lion smiled, but let the Mouse out. Not long after, the Mouse had a chance to repay him. The Lion was caught by some hunters, and bound with ropes to a tree. The Mouse heard him roar and groan, and ran and gnawed the ropes, so that the Lion got free.

Then the Mouse said:—

“You laughed at me once, Lion, as if you could get nothing in return for your kindness to me. But now it is you who owe your life to me.”

There was once a Shoemaker who worked very hard and was honest. Still, he could not earn enough to live on. At last, all he had in the world was gone except just leather enough to make one pair of shoes. He cut these out at night, and meant to rise early the next morning to make them up.

His heart was light in spite of his troubles, for his conscience was clear. So he went quietly to bed, left all his cares to God, and fell asleep. In the morning he said his prayers and sat down to work, when, to his great wonder, there stood the shoes, already made, upon the table.

The good man knew not what to say or think. He looked at the work. There was not one false stitch in the whole job. All was neat and true.

That same day a customer came in, and the shoes pleased him so well that he readily paid a price higher than usual for them. The Shoemaker took the money and bought leather enough to make two pairs more. He cut out the work in the evening and went to bed early. He wished to be up with the sun and get to work.

He was saved all trouble, for when he got up in the morning, the work was done. Pretty soon buyers came in, who paid him well for his goods. So he bought leather enough for four pairs more.

He cut out the work again over night, and found it finished in the morning as before. So it went on for some time. What was got ready at night was always done by daybreak, and the good man soon was well to do.

One evening, at Christmas time, he and his wife sat over the fire, chatting, and he said:—

“I should like to sit up and watch to-night, that we may see who it is that comes and does my work for me.” So they left the light burning, and hid themselves behind a curtain to see what would happen.

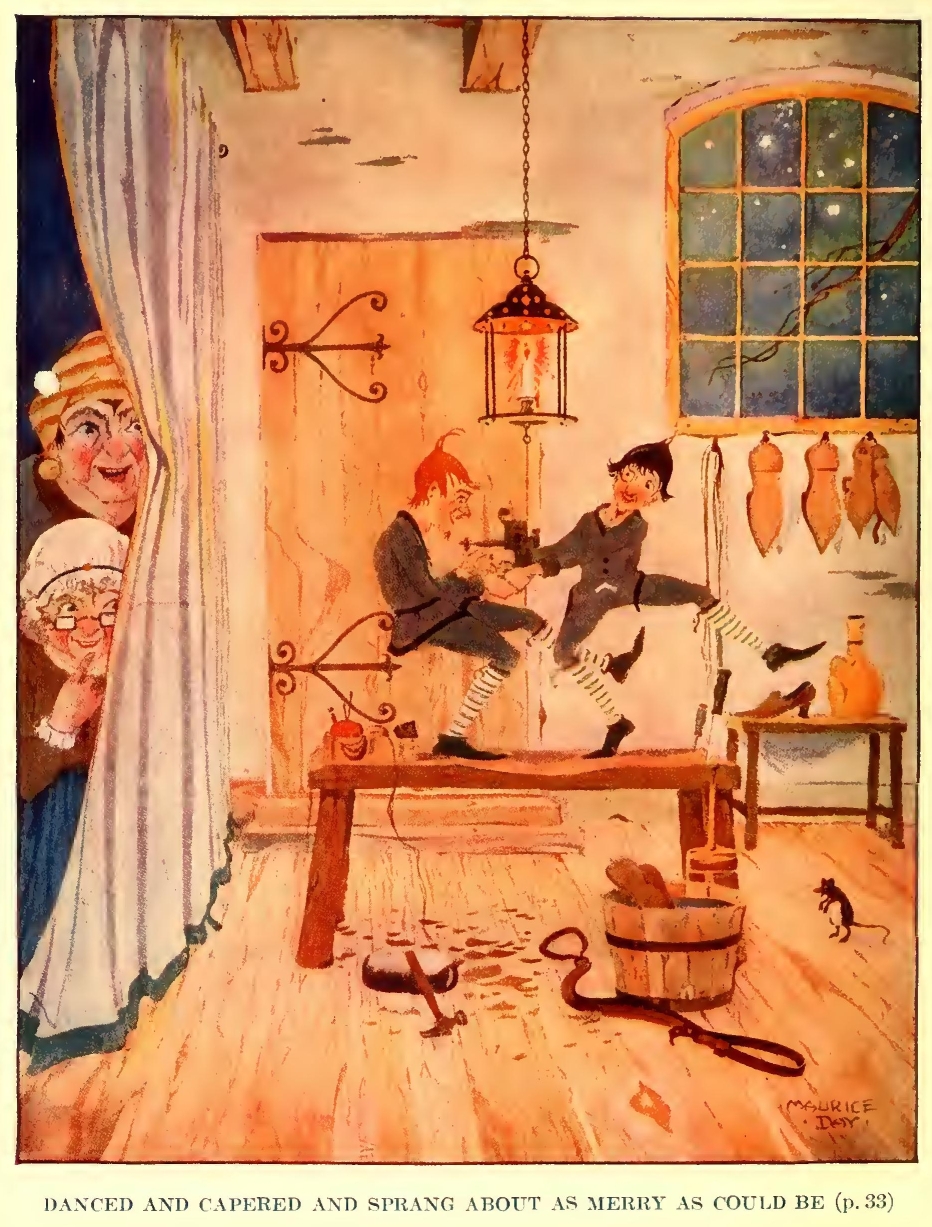

As soon as it was midnight, there came two little Elves. They sat upon the Shoemaker’s bench, took up all the work that was cut out, and began to ply their little fingers. They stitched and rapped and tapped at such a rate that the Shoemaker was amazed, and could not take his eyes off them for a moment.

On they went till the job was done, and the shoes stood, ready for use, upon the table. This was long before daybreak. Then they ran away as quick as lightning. The next day the wife said to the Shoemaker:—

“These little Elves have made us rich, and we ought to be thankful to them and do them some good in return. I am vexed to see them run about as they do. They have nothing upon their backs to keep off the cold. I’ll tell you what we must do; I will make each of them a shirt, and a coat and waistcoat, and a pair of pantaloons into the bargain. Do you make each of them a little pair of shoes.”

The good Shoemaker liked the thought very well. One evening, he and his wife had the clothes ready, and laid them on the table instead of the work they used to cut out. Then they went and hid behind the curtain to watch what the little Elves would do.

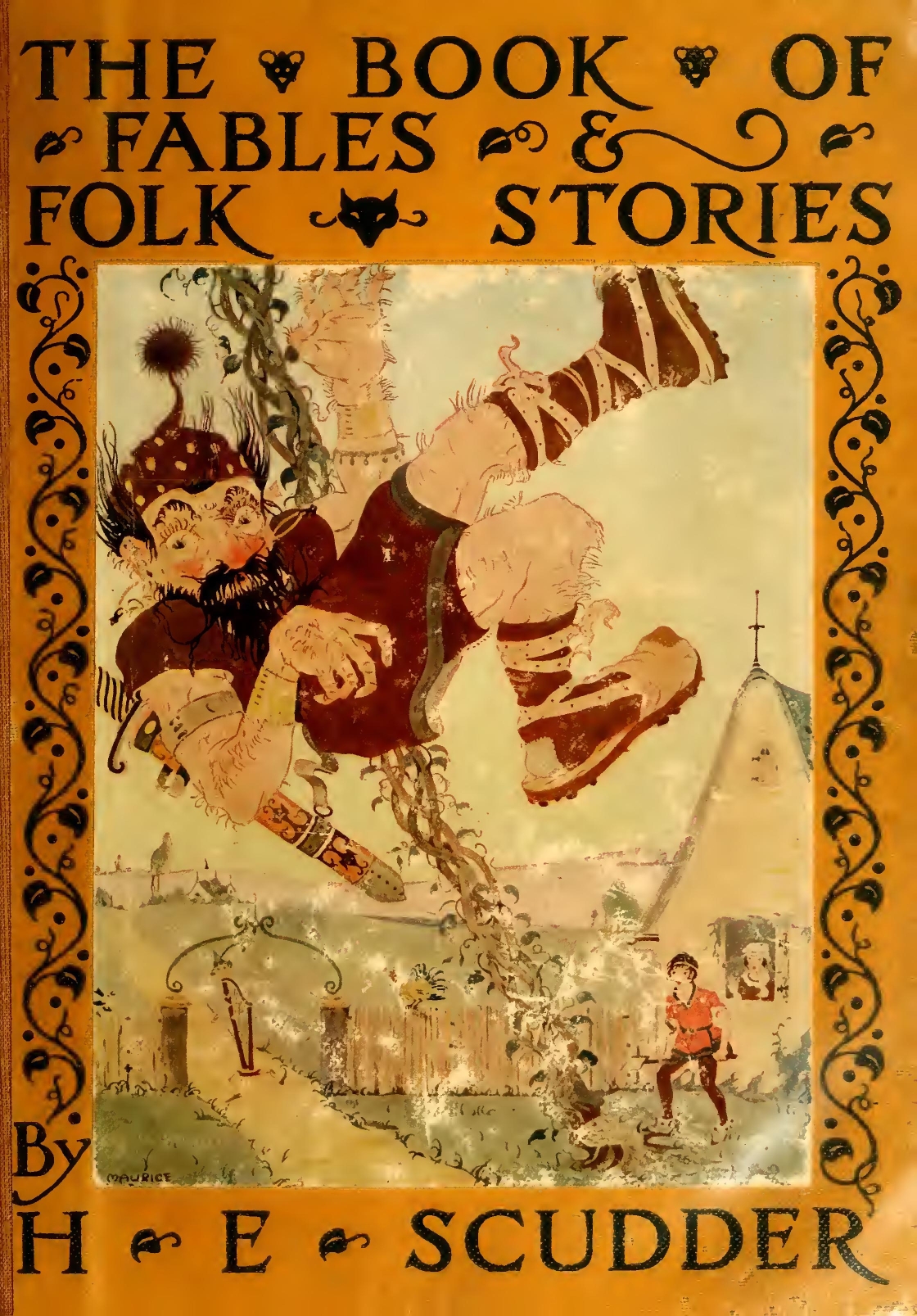

At midnight the Elves came in and were going to sit down at their work as usual. But when they saw the clothes lying there for them, they laughed and were in high glee.

They dressed themselves in the twinkling of an eye, and danced and capered and sprang about as merry as could be, till at last they danced out of the door, and over the green.

The Shoemaker saw them no more, but everything went well with him as long as he lived.

A thirsty Stag came to a spring to drink. As he drank, he looked into the water and saw himself. He was very proud of his horns, when he saw how big they were and what branches they had. But he looked at his feet, and took it hard that they should be so thin and weak.

Now, while he was thinking about these things, a Lion sprang out and began to chase him. The Stag turned and ran. As he was very fleet, he outran the Lion so long as they were on the open plain. But when they came to a piece of woods, the Stag’s horns became caught in the branches of the trees. He could not run, and the Lion caught up with him.

As the Lion fell upon him with his claws, the Stag cried oat:—

“What a wretch am I! I was made safe by the very parts I scorned, and have come to my end by the parts I gloried in!”

A certain wise man was wont to go out every evening and gaze at the stars. Once his walk took him outside of the town, and as he was looking earnestly into the sky, he fell into a ditch.

He was in a sad plight, and set up a cry. A man who was passing by heard him, and stopped to see what was the matter.

“Ah, sir,” said he, “when you are trying to make out what is in the sky, you do not see what is on the earth.”

A Fox who had never seen a Lion happened one day to meet one. When he saw him, he was so afraid that he almost died. When he met him a second time, he was afraid, to be sure, but not as at first. The third time he saw him, the Fox was so bold that he went up to the Lion and spoke to him.

This fable teaches that, when we get used to fearful things, they do not frighten us so much as at first.

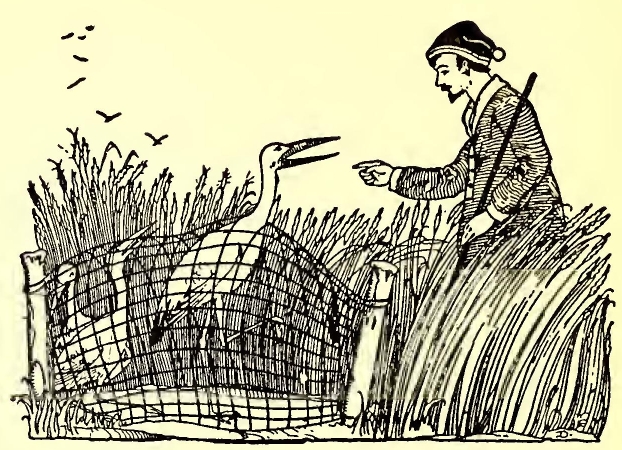

A Farmer set a net in his field to catch the Cranes that were eating his grain. He caught the Cranes, and with them a Stork also. The Stork was lame, and begged the Farmer to let him go.

“I am not a Crane,” he said. “I am a Stork. I am a very good bird, and take care of my father and mother. Look at the color of my skin; it is not the same as the Crane’s.”

But the Farmer said: “I do not know how that is. I caught you with the Cranes, and with the Cranes you must die.”

It is well to keep out of the way of wicked people, lest we fall into the trap with them.

A Dog was lying asleep in front of a stable. A Wolf suddenly came upon him, and was about to eat him, but the Dog begged for his life, saying:—

“I am lean and tough now; but wait a little, for my master is going to give a feast, and then I shall have plenty to eat; I shall grow fat, and make a better meal for you.”

So the Wolf agreed, and went away. By and by he came back, and found the Dog asleep on the house-top. He called to him to come down now and do as he had agreed. But the Dog answered:—

“Good Wolf, if you ever catch me again asleep in front of the stable, you had better not wait for the feast to come off.”

This fable teaches that wise men, when they escape danger, take care afterwards not to run the same risk.

An unlucky Fox fell into a well, and cried out for help. A Wolf heard him, and looked down to see what the matter was.

“Ah!” said the Fox, “pray lend a hand, friend, and get me out of this.”

“Poor creature,” said the Wolf, “how did this come about? How long have you been here? You must be very cold.”

“Come, come,” says the Fox, “this is no time for pitying and asking questions; get me out of the well first, and I will tell you all about it afterwards.”

Every man carries two Packs, one in front, the other behind, and each is full of faults. But the one in front holds other people’s faults, the one behind holds his own. And so it is that men do not see their own faults at all, but see very clearly the faults of others.

A Dog, with a bit of meat in his mouth, was crossing a river. Looking down he saw his image in the water, and thought it was another dog, with a bigger piece. So he dropped what he had, and jumped into the water after the other piece. Thus he lost both pieces: the one he really had, which he dropped; and the other he wanted, which was no piece at all.

This is a good fable for greedy people.

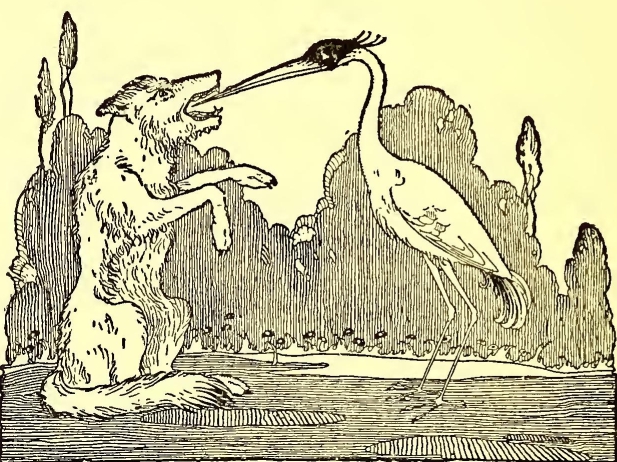

The Fox invited the Stork to sup with him, and placed a shallow dish on the table. The Stork, with her long bill, could get nothing out of the dish, while the Fox could lap up the food with his tongue; and so the Fox laughed at the Stork.

The Stork, in her turn, asked the Fox to dine with her. She placed the food in a long-necked jar, from which she could easily feed with her bill, while the Fox could get nothing. That was tit for tat.

A wild young fellow, who had spent all his father’s money, and had only a cloak left upon his back, when he saw a Swallow flying about before it was time said: “Ah, summer has come! I shall not need my cloak any longer; so I will sell it.” But afterwards a storm came, and, when it was past, he saw the poor Swallow dead on the ground. “Ah, my friend!” said he, “you are lost yourself, and you have ruined me.”

One Swallow does not make a summer.

In the days of King Alfred a poor woman lived in a country village in England. She had an only son, Jack, who was a good-natured, idle boy. She was too easy with him. She never set him at work, and soon there was nothing left them but their cow. Then the mother began to weep and to think that she had brought up her boy very ill.

“Cruel boy!” she said. “You have at last made me a beggar. I have not money enough to buy a bit of bread. We cannot starve. We must sell the cow, and then what shall we do?”

At first Jack felt very badly and wished he had done better. But soon he began to think what fun it would be to sell the cow. He begged his mother to let him go with the cow to the nearest village. She was not very willing. She did not believe Jack knew enough to sell a cow, but at last she gave him leave.

Off went Jack with the cow. He had not gone far when he met a Butcher.

“Where are you going with your cow?” asked the Butcher.

“I am going to sell it,” said Jack. The Butcher held his hat in his hand and shook it. Jack looked into the hat and saw some odd-looking beans. The Butcher saw him eye them. He knew how silly Jack was, so he said to him:—

“Well, if you wish to sell your cow, sell her to me. I will give you all these beans for her.”

Jack thought this a fine bargain. He gave the Butcher the cow and took the beans. He ran all the way home and could hardly wait to reach the house. He called out to his mother to see what he had got for the cow.

When the poor woman saw only a few beans, she burst into tears. She was so vexed that she threw the beans out of the window. She did not even cook them for supper. They had nothing else to eat, and they went to bed hungry.

Jack awoke early the next morning and thought it very dark. He went to the window and could hardly see out of it, for it was covered with something green. He ran downstairs and into the garden. There he saw a strange sight.

The beans had taken root and shot up toward the clouds. The stalks were as thick as trees, and were wound about each other. It was like a green ladder, and Jack at once wished to climb to the top.

He ran in to tell his mother, but she begged him not to climb the bean-stalk. She did not know what would happen. She was afraid to have him go. Who ever saw such bean-stalks before?

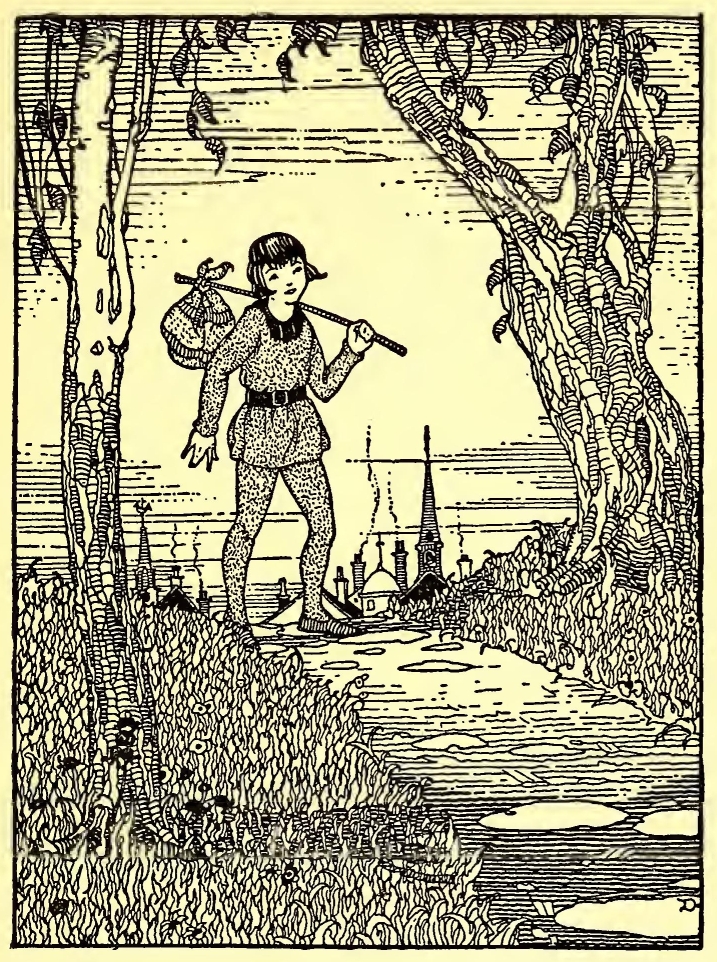

But Jack had set his heart on climbing, and he told his mother not to be afraid. He would soon see what it all meant. So up he climbed. He climbed for hours. He went higher and higher, and at last, quite tired out, he reached the top.

Then he looked about him. It was all new. He had never seen such a place before. There was not a tree or plant; there was no house or shed. Some stones lay here and there, and there were little piles of earth. He could not see a living person.

Jack sat down on one of the stones. He wished he were at home again. He thought of his mother. He was hungry, and he did not know where to get anything to eat. He walked and walked, and hoped he might see a house.

He saw no house, but at last he saw a lady walking alone. He ran toward her, and when he came near, he pulled off his cap and made a bow. She was a beautiful lady, and she carried in her hand a stick. A peacock of fine gold sat on top of the stick.

The lady smiled and asked Jack how he came there. He told her all about the bean-stalk. Then she said:—

“Do you remember your father?”

“No,” said Jack. “I do not know what became of him. When I speak of him to my mother, she cries, but she tells me nothing.”

“She dare not,” said the lady, “but I will tell you. I am a fairy. I was set to take care of your father, but one day I was careless. So I lost my power for a few years, and just when your father needed me most I could not help him, and he died.”

Jack saw that she was very sorry as she told this story, but he begged her to go on.

“I will,” she said, “and you may now help your mother. But you must do just as I tell you.”

Jack promised.

“Your father was a good, kind man. He had a good wife, he had money, and he had friends. But he had one false friend. This was a Giant. Your father had once helped this Giant, but the Giant was cruel. He killed your father and took all his money. And he told your mother she must never tell you about your father. If she did, then the Giant would kill her and kill you too.

“You were a little child then, and your mother carried you away in her arms. I could not help her at the time, but my power came back to me yesterday. So I made you go off with the cow, and I made you take the beans, and I made you climb the bean-stalk.

“This is the land where the Giant lives. You must find him and rid the world of him. All that he has is yours, for he took it from your father. Now go. You must keep on this road till you see a great house. The Giant lives there. I cannot tell you what you must do next, but I will help you when the time comes. But you must not tell your mother anything.”

The fairy disappeared and Jack set out. He walked all day, and when the sun set, he came to the Giant’s house. He went up to it and saw a plain woman by the door. This was the Giant’s wife. Jack spoke to her and asked her if she would give him something to eat and a place where he could sleep.

“What!” she said. “Do you not know? My husband is a Giant. He is away now, but he will be back soon. Sometimes he walks fifty miles in a day to see if he can find a man or a boy. He eats people. He will eat you if he finds you here.”

Jack was in great fear, but he would not give up. He asked the Giant’s wife to hide him somewhere in the house. She was a kind woman, so she led him in. They went through a great hall, and then through some large rooms. They came to a dark passage, and went through it. There was a little light, and Jack could see bars of iron at the side. Behind the bars were wretched people. They were the prisoners of the Giant.

Poor Jack thought of his mother and wished himself at home again. He began to think the Giant’s wife was as bad as the Giant, and had brought him in to shut him up here. Then he thought of his father and marched boldly on.

They came to a room where a table was set. Jack sat down and began to eat. He was very hungry and soon forgot his fears. But while he was eating, there came a loud knock at the outside door. It was so loud that the whole house shook. The Giant’s wife turned pale.

“What shall I do?” she cried. “It is the Giant. He will kill you and kill me too! What shall I do?”

“Hide me in the oven,” said Jack. There was no fire under it, and Jack lay in the oven and looked out. The Giant came in and scolded his wife, and then he sat down and ate and drank for a long time. Jack thought he never would finish. At last the Giant leaned back in his chair and called out in a loud voice:—

“Bring me my hen!”

His wife brought a beautiful hen and placed it on the table.

“Lay!” roared the Giant, and the hen laid an egg of solid gold.

“Lay another!” And the hen laid another. So it went on. Each time the hen laid a larger egg than before. The Giant played with the hen for some time. Then he sent his wife to bed, but he sat in his chair. Soon he fell asleep, and then Jack crept out of the oven and seized the hen. He ran out of the house and down the road. He kept on till he came to the bean-stalk, and climbed down to his old home.

Jack’s mother was very glad to see him. She was afraid that he had come to some ill end. “Not a bit of it, mother,” said he. “Look here!” and he showed her the hen. “Lay!” he said to the hen, and the hen laid an egg of gold.

Jack and his mother now had all they needed, for they had only to tell the hen to lay, and she laid her golden egg. They sold the egg and had money enough. But Jack kept thinking of his father, and he longed to make another trial. He had told his mother about the Giant and his wife, but he had said nothing about the fairy and his father.

His mother begged Jack not to climb the beanstalk again. She said the Giant’s wife would be sure to know him, and he never would come back alive. Jack said nothing, but he put on some other clothes and stained his face and hands another color. Then, one morning, he rose early and climbed the bean-stalk a second time.

He went straight to the Giant’s house. The Giant’s wife was again at the door, but she did not know him. He begged for food and a place to sleep. She told him about the Giant, and then she said:—

“There was once a boy who came just as you have come. I let him in, and he stole the Giant’s hen and ran away. Ever since the Giant has been very cruel to me. No, I cannot let you come in.”

But Jack begged so hard that at last she let him in. She led him through the house, and he saw just what he had seen before. She gave him something to eat, and then she hid him in a closet. The Giant came along in his heavy boots. He was so big, that the house shook. He sat by the fire for a time. Then he looked about and said:—

“Wife, I smell fresh meat.”

“Yes,” she said. “The crows have been flying about. They left some raw meat on top of the house.”

Then she made haste and got some supper for the giant.

He was very cross. So it went on as before. The Giant ate and drank. Then he called to his wife:—

“Bring me something. I want to be amused. You let that rascal steal my hen. Bring me something.”

“What shall I bring?” she asked meekly.

“Bring me my money-bags; they are as heavy as anything.” So she tugged two great bags to the table. One was full of silver and one was full of gold. The Giant sent his wife to bed. Then he untied the strings, emptied his bags, and counted his money. Jack watched him, and said to himself:—

“That is my father’s money.”

By and by the Giant was tired. He put the money back into the bags and tied the strings. Then he went to sleep. He had a dog to watch his money, but Jack did not see the dog. So when the Giant was sound asleep, Jack came out of the closet and laid hold of the bags.

At this the dog barked, and Jack thought his end had come. But the Giant did not wake, and Jack just then saw a bit of meat. He gave it to the dog, and while the dog was eating it, Jack took the two bags and was off.

It was two whole days before he could reach the bean-stalk, for the bags were very heavy. Then he climbed down with them. But when he came to his house the door was locked. No one was inside, and he knew not what to do.

After a while he found an old woman who showed him where his mother was. She was very sick in another house. The poor thing had been made ill by Jack’s going away. Now that he had come back, she began to get well, and soon she was in her own house again.

Jack said no more about the Giant and the bean-stalk. For three years he lived with his mother. They had money enough, and all seemed well. But Jack could not forget his father. He sat all day before the bean-stalk. His mother tried hard to amuse him, and she tried to find out what he was thinking about. He did not tell her, for he knew all would then go wrong.

At last he could bear it no longer. He had changed in looks now, and he changed himself still more. Then, one bright summer morning, very early in the day, he climbed the bean-stalk once more. The Giant’s wife did not know him when he came to the door of the house. He had hard work to make her let him in.

This time he was hidden in the copper boiler.

The Giant again came home, and was in a great rage.

“I smell fresh meat!” he cried. His wife could do nothing with him, and he began to go about the room. He looked into the oven, and into the closet, and then he came to the great boiler. Jack felt his heart stop. He thought now his end had come, surely. But the Giant did not lift the lid. He sat down by the fire and had his supper.

When supper was over, the Giant told his wife to bring his harp. Jack peeped out of the copper and saw a most beautiful harp. The Giant placed it on the table, and said:—

“Play!”

Jack never heard such music as the harp played. No hands touched it. It played all by itself. He thought he would rather have this harp than the hen or all the money. By and by the harp played the Giant to sleep. Then Jack crept out and seized the harp. He was running off with it, when some one called loudly:—

“Master! Master!”

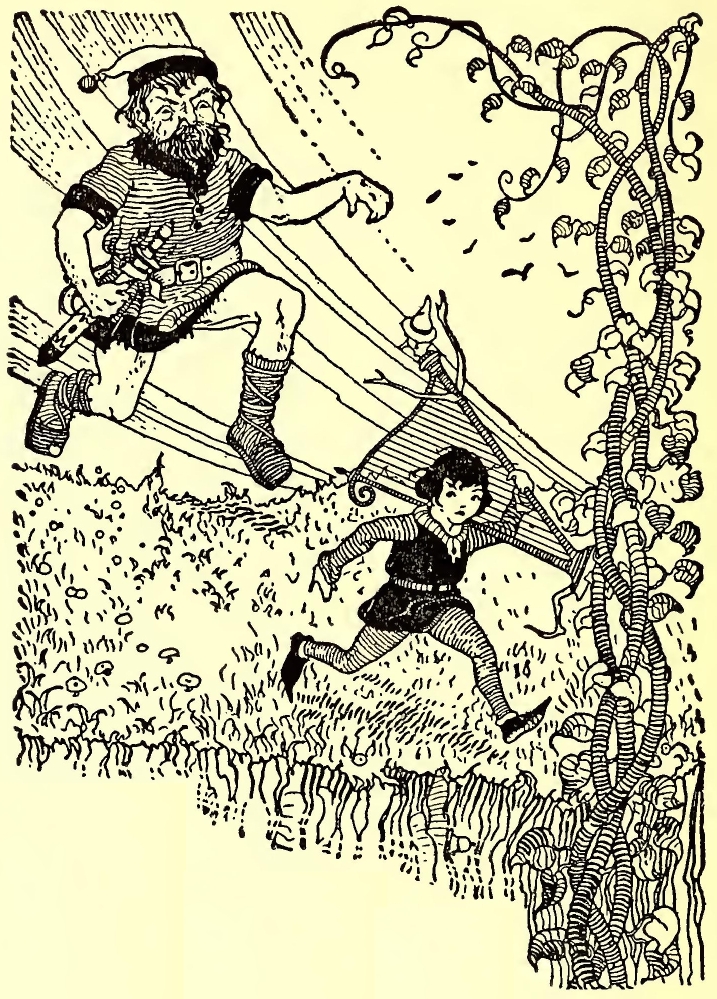

It was the harp, but Jack would not let it go. The Giant started up, and saw Jack with the harp running down the road.

“Stop, you rascal!” he shouted. “You stole my hen and my money-bags. Do you steal my harp? I’ll catch you, and I’ll break every bone in your body!”

“Catch me if you can!” said Jack. He knew he could run faster than the Giant. Off they went, Jack and the harp, and the Giant after them. Jack came to the bean-stalk. The harp was all the while playing music, but now Jack said:—

“Stop!” and the harp stopped playing. He hurried down the bean-stalk with the harp. There sat his mother, by the cottage, weeping.

“Do not cry, mother,” he said. “Quick, bring me a hatchet! Make haste!” He knew there was not a minute to spare. The Giant was already coming down. He was half-way down when Jack took his hatchet and cut the beanstalk down, close to its roots. Over fell the bean-stalk, and down came the Giant upon the ground. He was killed on the spot.

In a moment the fairy was seen. She told Jack’s mother everything, and how brave he had been. And that was the end. The beanstalk never grew again.

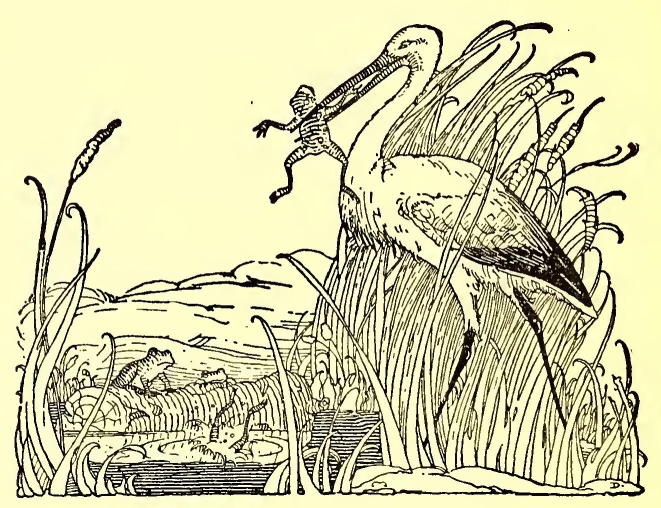

An Ox, grazing in a swampy meadow, set his foot among a number of young Frogs, and crushed nearly all to death. One that escaped ran off to his mother with the dreadful news.

“Oh, mother,” said he, “it was a beast—such A big, four-footed beast, that did it!”

“Big?” said the old Frog. “How big? Was it as big as this?” and she puffed herself out. “Oh, a great deal bigger than that.”

“Well, was it so big?” and she swelled herself out more.

“Indeed, mother, it was; and if you were to burst yourself, you would never reach half its size.” The old Frog made one more trial, determined to be as big as the Ox, and burst herself indeed.

A Miller and his Son were driving their Ass to the fair to sell him. They had not gone far, when they met a troop of girls, returning from the town, talking and laughing.

“Look there!” cried one of them. “Did you ever see such fools, to be trudging along on foot, when they might be riding?” The Miller, when he heard this, bade his Son get up on the Ass, and walked along merrily by his side. Soon they came to a group of old men talking gravely.

“There!” said one of them; “that proves what I was saying. What respect is shown to old age in these days? Do you see that idle young rogue riding, while his father has to walk? Get down, lazy boy, and let the old man get on!”

The Son got down from the Ass, and the Miller took his place. They had not gone far when they met a company of women and children.

“Why, you lazy old fellow!” cried several at once. “How can you ride upon the beast, when that poor little lad can hardly keep up with you?”

So the good-natured Miller took his Son up behind him. They had now almost reached the town.

“Pray, my friend,” said a townsman, “is that Ass your own?”

“Yes,” said the Miller.

“I should not have thought so,” said the other, “by the way you load him. Why, you two are better able to carry the poor beast than he to carry you.”

“Anything to please you,” said the Miller. So he and his Son got down from the Ass. They tied his legs together, and, taking a stout pole, tried to carry him on their shoulders over a bridge that led to the town.

This was so odd a sight that crowds of people ran out to see it, and to laugh at it. The Ass, not liking to be tied, kicked the cords away, and tumbled off the pole into the water. At this the Miller and his Son hung down their heads. They made their way home again, having learned that by trying to please everybody, they had pleased nobody, and lost the Ass into the bargain.

Once upon a time there lived a man and his wife and one beautiful daughter. The wife fell sick and died, and some time after the father married again, for he needed some one to take care of his child. The new wife appeared very well before the wedding, but afterward she showed a bad temper. She had two children of her own, and they were proud and unkind like their mother. They could not bear their gentle sister, and they made her do all the hard work.

She washed the dishes, and scrubbed the stairs. She swept the floor in my lady’s chamber, and took care of the rooms of the two pert misses. They slept on soft beds in fine rooms, and had tall looking-glasses, so that they could admire themselves from top to toe. She lay on an old straw sack in the garret.

She bore all this without complaint. She did her work, and then sat in the corner among the ashes and cinders. So her two sisters gave her the name of Cinderella or the cinder-maid. But Cinderella was really much more beautiful than they; and she surely was more sweet and gentle.

Now the king’s son gave a ball, and he invited all the rich and the grand. Cinderella’s two sisters were fine ladies; they were to go to the ball. Perhaps they would even dance with the prince. So they had new gowns made, and they looked over all their finery.

Here was fresh work for poor Cinderella. She must starch their ruffles and iron their linen. All day long they talked of nothing but their fine clothes.

“I shall wear my red velvet dress,” said the elder, “and trim it with my point lace.”

“And I,” said the younger sister, “shall wear a silk gown, but I shall wear over it a gold brocade, and I shall put on my diamonds. You have nothing so fine.”

Then they began to quarrel over their clothes, and Cinderella tried to make peace between them. She helped them about their dresses, and offered to arrange their hair on the night of the ball.

While she was thus busy, the sisters said to her:—

“And pray, Cinderella, would you like to go to the ball?”

“Nay,” said the poor girl; “you are mocking me. It is not for such as I to go to balls.”

“True enough,” they said. “Folks would laugh to see a cinder-maid at a court ball.”

Any one else would have dressed their hair ill to spite them for their rudeness. But Cinderella was good-natured, and only took more pains to make them look well.

The two sisters scarcely ate a morsel for two days before the ball. They wished to look thin and graceful. They lost their tempers over and over, and they spent most of the time before their tall glasses. There they turned and turned to see how they looked behind, and how their long trains hung.

At last the evening came, and off they set in a coach. Cinderella watched them till they were out of sight, and then she sat down by the kitchen fire and began to weep.

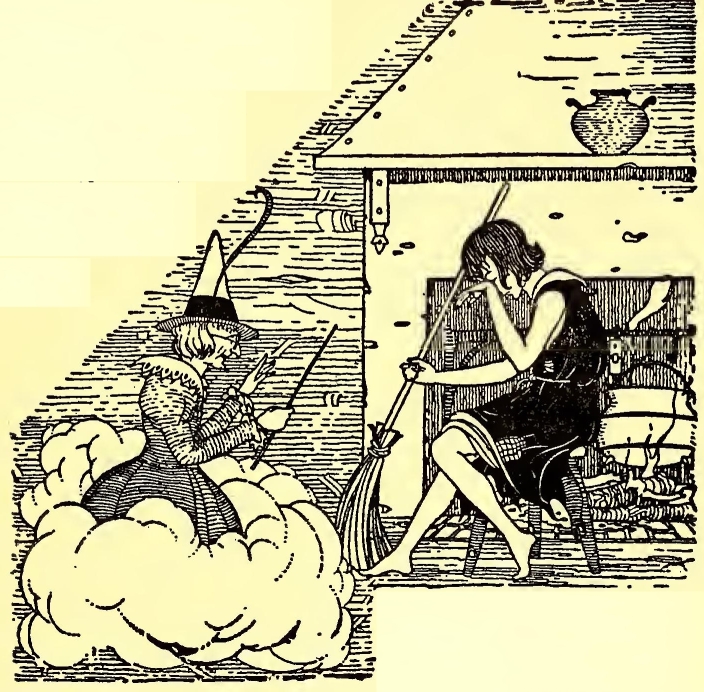

All at once her fairy godmother appeared, with her wand.

“What are you crying for, my little maid?”

“I wish—I wish,” began the poor girl, but her voice was choked with tears.

“You wish that you could go to the ball?”

Cinderella nodded.

“Well, then, if you will be a good girl, you shall go. Run quick and fetch me a pumpkin from the garden.”

Cinderella flew to the garden and brought back the finest pumpkin she could find. She could not guess what use it would be, but the fairy scooped it hollow, and then touched it with her wand. The pumpkin became at once a splendid gilt coach.

“Now fetch me the mouse-trap from the pantry.”

In the mouse-trap were six sleek mice. The fairy opened the door, and as they ran out she touched each with her wand, and it became a gray horse. But what was she to do for a coachman?

“We might look for a rat in the rat-trap,” said Cinderella.

“That is a good thought. Run and bring the rat-trap, my dear.”

Back came Cinderella with the trap. In it were three large rats. The fairy chose one that had long black whiskers, and she made him the coachman.

“Now go into the garden and bring me six lizards. You will find them behind the water-pot.”

These were no sooner brought than, lo! with a touch of the wand they were turned into six footmen, who jumped up behind the coach, as if they had done nothing else all their days. Then the fairy said:—

“Here is your coach and six, Cinderella; your coachman and your footmen. Now you can go to the ball.”

“What! in these clothes?” and Cinderella looked down at her ragged frock. The fairy laughed, and just touched her with the wand. In a twinkling, her shabby clothes were changed to a dress of gold and silver lace, and on her bare feet were silk stockings and a pair of glass slippers, the prettiest ever seen.

“Now go to the ball, Cinderella; but remember, if you stay one moment after midnight, your coach will instantly become a pumpkin, your horses will be mice, your coachman a rat, and your footmen lizards. And you? You will be once more only a cinder-maid in a ragged frock and with bare feet.”

Cinderella promised and drove away in high glee. She dashed up to the palace, and her coach was so fine that the king’s son came down the steps of the palace to hand out this unknown princess. He led her to the hall where all the guests were dancing.

The moment she appeared all voices were hushed, the music stopped, and the dancers stood still. Such a beautiful princess had never been seen! Even the king, old as he was, turned to the queen and said:—

“She is the most beautiful being I ever saw—since I first saw you!”

As for the ladies of the court, they were all busy looking at Cinderella’s clothes. They meant to get some just like them the very next day, if possible.

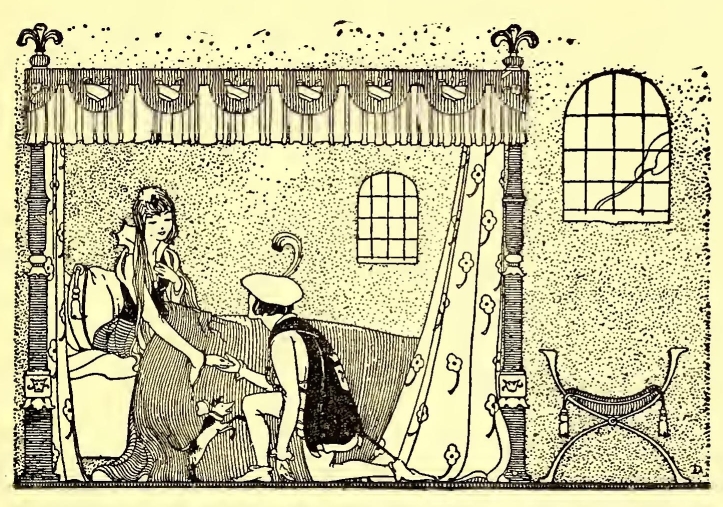

The prince led Cinderella to the place of highest rank, and asked her hand for the next dance. She danced with so much grace that he admired her more and more. Supper was brought in, but the prince could not keep his eyes off the beautiful stranger. Cinderella went and sat by her sisters, and shared with them the fruit which the prince gave her. They were very proud to have her by them, for they never dreamed who she really was.

Cinderella was talking with them, when she heard the clock strike the quarter hour before twelve. She went at once to the king and queen, and made them a low courtesy and bade them good-night. The queen said there was to be another ball the next night, and she must come to that. The prince led her down the steps to her coach, and she drove home.

At the house the fairy sat waiting for Cinderella. The maiden began to tell all that had happened, and was in the midst of her story, when a knock was heard at the door. It was the sisters coming home from the ball. The fairy disappeared, and Cinderella went to the door, rubbing her eyes, as if she had just waked from a nap. She was once more a poor little cinder-maid.

“How late you are!” she said, as she opened the door.

“If you had been to the ball, you would not have thought it late,” said her sisters. “There came the most beautiful princess that ever was seen. She was very polite to us, and loaded us with oranges and grapes.”

“Who was she?” asked Cinderella.

“Nobody knew her name. The prince would give his eyes to know.”

“Ah! how I should like to see her,” said Cinderella. “Oh, do, my Lady Javotte,”—that was the name of the elder sister,—“lend me the yellow dress you wear every day, and let me go to the ball and have a peep at the beautiful princess.”

“What! lend my yellow gown to a cinder-maid! I am not so silly as that.”

Cinderella was not sorry to have Javotte say no; she would have been puzzled to know what to do if her sister had really lent her the dress she begged for.

The next night came, and the sisters again went to the court ball. After they had gone, the fairy came as before and made Cinderella ready.

“Now remember,” she said, as the coach drove away, “remember twelve o’clock.”

Cinderella was even more splendid than on the first night, and the king’s son never left her side He said so many pretty things that Cinderella could think of nothing else. She forgot the fairy’s warning; she forgot her promise. Eleven o’clock came, but she did not notice the striking. The half-hour struck, but the prince grew more charming, and Cinderella could hear nothing but his voice. The last quarter—but still Cinderella sat by the prince.

Then the great clock on the tower struck the first stroke of twelve. Up sprang Cinderella, and fled from the room. The prince started to follow her, but she was too swift for him; in her flight, one of her glass slippers fell from her feet, and he stopped to pick it up.

The last stroke of twelve died away, as Cinderella darted down the steps of the palace. In a twinkling the gay lady was gone; only a shabby cinder-maid was running down the steps. The splendid coach and six, driver and footman,—all were gone; only a pumpkin lay on the ground, and a rat, six mice, and six lizards scampered off.

Cinderella reached home, quite out of breath. She had saved nothing of all her finery but one little glass slipper. The prince had its mate, but he had lost the princess. He asked the soldiers at the palace gate if they had not seen her drive away. No; at that hour only a ragged girl had passed out.

Soon the two sisters came home from the ball, and Cinderella asked them if they had again seen the beautiful lady. Yes; she had been at the ball, but she had left suddenly, and no one knew what had become of her. But the prince would surely find her, for he had one of her glass slippers.

They spoke truly. A few days afterward, the king’s son sent a messenger with a trumpet and the slipper through all the city. The messenger sounded his trumpet and shouted that the prince would marry the lady who could wear the glass slipper. So the slipper was first tried on by all the princesses; then by all the duchesses; next by all the persons belonging to the court; but in vain: not one could wear it.

Then it was carried to all the fine houses, and it came at last to the two sisters. They tried with all their might to force a foot into the fairy slipper, but they could not. Cinderella stood by, and said:—

“Suppose I were to try.” Her two sisters jeered at her, but the messenger looked at Cinderella. He saw that she was very fair, and, besides, he had orders to try the slipper on the foot of every maiden in the kingdom, if need were.

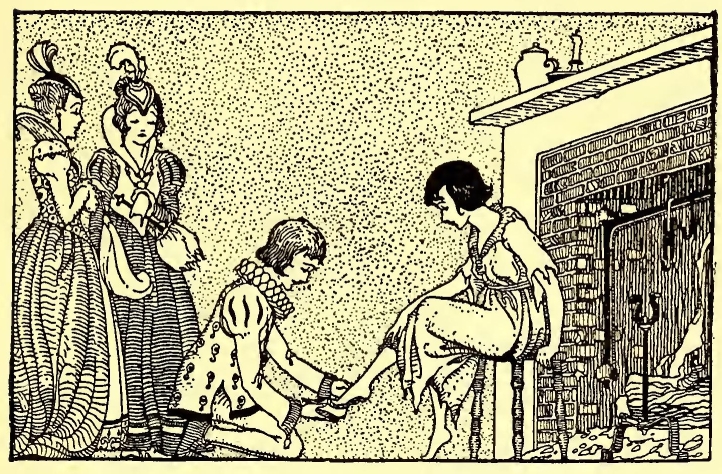

So he bade Cinderella sit down on a three-legged stool in the kitchen. She put out her little foot, and the slipper fitted like wax. The sisters stood in amaze. Then Cinderella put her hand into her pocket and drew forth the other glass slipper, and put it on her other foot.

The moment that Cinderella did this, the fairy, who stood by unseen, touched her with her wand, and the cinder-maid again became the beautiful, gayly dressed lady. The sisters saw that she was the same one whom they had seen at the ball. They thought how ill they had treated her all these years, and they fell at her feet and asked her to forgive them.

Cinderella was as good now as she had been when she was a cinder-maid. She freely forgave her sisters, and took them to the palace with her, for she was now to be the prince’s wife. And when the old king and queen died, the prince and Cinderella became King and Queen.

A Wolf once dressed himself in the skin of a Sheep, and so got in among the flock, where he killed a good many of them. At last the Shepherd found him out, and hanged him upon a tree as a warning to other wolves.

Some Shepherds going by saw the wolf, and thought it was a Sheep. They wondered why the Shepherd should hang a Sheep. So they asked him, and he answered: “I hang a Wolf when I catch him, even though he be dressed in a Sheep’s clothes.”

One cold night, as an Arab sat in his tent, a Camel thrust the flap of the tent aside, and looked in.

“I pray thee, master,” he said, “let me put my head within the tent, for it is cold without.”

“By all means, and welcome,” said the Arab; and the Camel stretched his head into the tent.

“If I might but warm my neck, also,” he said, presently.

“Put your neck inside,” said the Arab. Soon the Camel, who had been turning his head from side to side, said again:—

“It will take but little more room if I put my fore legs within the tent. It is difficult standing without.”

“You may also put your fore legs within,” said the Arab, moving a little to make room, for the tent was very small.

“May I not stand wholly within?” asked the Camel, finally. “I keep the tent open by standing as I do.”

“Yes, yes,” said the Arab. “I will have pity on you as well as on myself. Come wholly inside.”

So the Camel came forward and crowded into the tent. But the tent was too small for both.

“I think,” said the Camel, “that there is not room for both of us here. It will be best for you to stand outside, as you are the smaller; there will then be room enough for me.”

And with that he pushed the Arab a little, who made haste to get outside of the tent.

It is a wise rule to resist the beginnings of evil.

A poor woodman once sat by the fire in his cottage, and his wife sat by his side, spinning.

“How lonely it is,” said he, “for you and me to sit here by ourselves without any children to play about and amuse us.”

“What you say is very true,” said his wife, as she turned her wheel. “How happy should I be, if I had but one child. If it were ever so small, if it were no bigger than my thumb, I should be very happy and love it dearly.”

Now it came to pass that the good woman had her wish, for some time afterward she had a little boy who was healthy and strong, but not much bigger than her thumb. So they said:—

“Well, we cannot say we have not got what we wished for, and, little as he is, we will love him dearly!” and they called him Tom Thumb. They gave him plenty to eat, yet he never grew bigger. Still his eyes were sharp and sparkling, and he soon showed himself to be a bright little fellow, who always knew what he was about.

One day the woodman was getting ready to go into the wood to cut fuel, and he said:—

“I wish I had some one to bring the cart after me, for I want to make haste.”

“O father,” cried Tom, “I will take care of that. The cart shall be in the wood by the time you want it.” The woodman laughed and said:

“How can that be? You cannot reach up to the horse’s bridle.”

“Never mind that, father. If my mother will only harness the horse, I will get into his ear, and tell him which way to go.”

“Well,” said the father, “we will try for once.”

When the time came, the mother harnessed the horse to the cart, and put Tom into his ear. There the little man sat and told the beast how to go, crying out, “Go on,” and “Stop,” as he wanted. So the horse went on just as if the woodman were driving it himself.

It happened that the horse fell to trotting too fast, and Tom called out, “Gently, gently.” Just then two strangers came up.

“How odd it is,” one of them said. “There is a cart going along, and I hear a carter talking to the horse, but I see no one.”

“That is strange,” said the other. “Let us follow the cart and see where it goes.” They went on into the wood, and came at last to the place where the woodman was. The cart drove up and Tom said:—

“See, father, here I am with the cart, safe and sound. Now, take me down.”

So his father took hold of the horse with one hand, and lifted his son down with the other. He put him on a little stick, where he was as merry as you please. The two strangers looked on and saw it all, and did not know what to say for wonder. At last one took the other aside and said:—

“That little chap will make our fortune if we can get him, and carry him about from town to town as a show. We must buy him.” Then they went to the woodman and asked him what he would take for the little man. “He will be better off with us than with you,” they said.

“I’ll not sell him at all,” said the father. “My own flesh and blood is dearer to me than all the silver and gold in the world.”

But Tom heard what was said, and crept up his father’s coat to his shoulder, and spoke in his ear:—

“Take the money, father, and let them have me. I’ll soon come back to you.” So the woodman at last agreed to sell Tom Thumb to the strangers for a large piece of gold.

“Where do you like to sit?” one of them asked Tom.

“Oh, put me on the rim of your hat; that will be a nice place for me. I can walk about there and see the country as we go along.”

They did as he wished. Tom took leave of his father, and went off with the two strangers. They kept on their way till it began to grow dark. Then Tom said:—

“Let me get down, I am tired.” So the man took off his hat, and set him down on a lump of earth in a ploughed field, by the side of the road. But Tom ran about among the furrows, and at last slipped into an old mouse-hole.

“Good-night, masters. I’m off,” said he.

“Look sharp after me next time.” They ran to the place and poked the ends of their sticks into the mouse-hole, but all in vain. Tom crawled farther in. They could not get him, and as it was now quite dark they went away very cross.

When Tom found they were gone, he crept out of his hiding-place.

“How dangerous it is,” said he, “to walk about in this ploughed field. If I were to fall from one of those big lumps I should surely break my neck.” At last, he found a large, empty snail-shell.

“This is lucky,” said he. “I can sleep here very well,” and in he crept. Just as he was falling asleep he heard two men pass by, and one said to the other:—

“How shall we manage to steal that rich farmer’s silver and gold?”

“I’ll tell you!” cried Tom.

“What noise was that? I am sure I heard some one speak,” said the thief. He was in a great fright. They both stood listening, and Tom spoke up:—

“Take me with you, and I will show you how to get the farmer’s money.”

“But where are you?”

“Look about on the ground, and listen where the sound comes from.”

“What a little chap! What can you do for us?”

“Why, I can get between the iron window bars, and throw you out whatever you want.”

“That is a good thought. Come along; we will see what you can do.”

When they came to the farmer’s house, Tom slipped through the bars into the room, and then called out as loud as he could:—

“Will you have all that is here?”

“Softly, softly!” said the thieves. “Speak low, or you will wake somebody.”

Tom made as if he did not understand them, and bawled out again:—

“How much will you have? Shall I throw it all out?”

Now the cook lay in the next room, and hearing a noise, she raised herself in her bed and listened. But the thieves had been thrown into a fright and had run away. By and by they plucked up courage, and said:—

“That little fellow is only trying to make fools of us.” So they came back and spoke low to him, saying: “Now let us have no more of your jokes, but throw out some of the money.” Then Tom called out again as loud as he could:—

“Very well! Hold your hands; here it comes.”

The cook heard this plainly; she sprang out of bed, and ran to open the door. The thieves were off as if a wolf were after them, and the cook could see nothing in the dark. So she went back for a light, and while she was gone, Tom slipped off into the barn.

The cook looked about and searched every hole and corner, but found nobody; she went back to bed, and thought she must have been dreaming with her eyes open. Tom crawled about in the hayloft, and at last found a good place to rest in. He meant to sleep till daylight, and then find his way home to his father and mother.

Poor Tom Thumb! his troubles were only begun. The cook got up early to feed the cows. She went straight to the hayloft, and carried away a large bundle of hay, with the little man in the middle of it fast asleep. He slept on, and did not wake till he found himself in the mouth of a cow. She had taken him up with a mouthful of hay.

“Dear me,” said he, “how did I manage to tumble into the mill?” But he soon found out where he was, and he had to keep all his wits about him, or he would have fallen between the cow’s teeth, and then he would have been crushed to death. At last he went down into her stomach.

“It is rather dark here,” said he; “they forgot to build windows in this room to let the sun in.” He made the best of his bad luck, but he did not like his resting-place at all. The worst of it was, that more and more hay was coming down, and there was less and less room to turn round in. At last he cried out as loud as he could:—

“Don’t bring me any more hay! don’t bring me any more hay!” The cook just then was milking the cow. She heard some one speak, but she saw nobody. Yet she was sure it was the same voice she had heard in the night. It put her into such a fright that she fell off her stool and upset her milk-pail. She ran off as fast as she could to the farmer, and said:—

“Sir, sir, the cow is talking.” But the farmer said:—

“Woman, thou art surely mad.” Still, he went with her into the cow-house, to see what was the matter. Just as they went in, Tom cried out again:—

“Don’t bring me any more hay! don’t bring me any more hay!” Then the farmer was in a fright. He was sure the cow must be mad, so he gave orders to have her killed at once. The cow was killed, and the stomach with Tom in it was thrown into the barnyard.

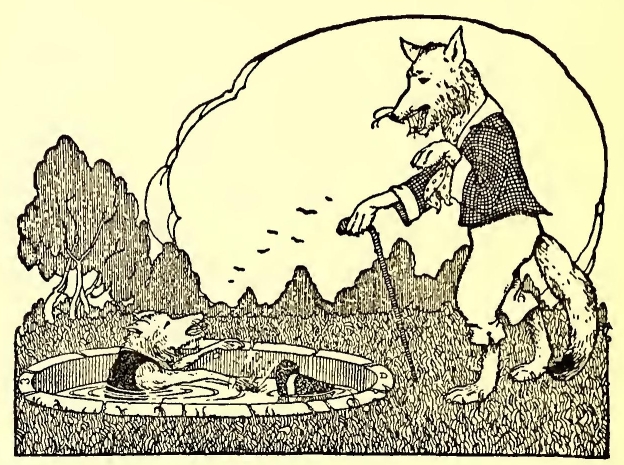

Tom soon set himself to work to get out, and that was not a very easy task. A hungry wolf was prowling about. Just as Tom had made room to get his head out the wolf seized the stomach and swallowed it. Off he ran, but Tom was not cast down. He began to chat with the wolf, and called out:—

“My good friend, I can show you a famous treat.”

“Where is that?”

“In the house near the wood. You can crawl through the drain into the kitchen, and there you will find cakes, ham, beef, and everything that is nice.” This was the house where Tom Thumb lived. The wolf did not need to be asked twice. That very night he went to the house and crawled through the drain into the kitchen. There he ate and drank to his heart’s content.

After a while he had eaten so much that he was ready to go away. But now he could not squeeze through the drain. This was just what Tom had thought of, and the little chap set up a great shout.

“Will you be quiet?” said the wolf. “You will wake everybody in the house.”

“What is that to me?” said the little man. “You have had your frolic; now I have a mind to be merry myself.” And he began again to sing and shout as loud as he could.

The woodman and his wife were awakened by the noise, and peeped through a crack into the kitchen. When they saw a wolf there, they were in a great fright. The woodman ran for his axe, and gave his wife a scythe.

“You stay behind,” said the woodman.

“When I have knocked the wolf on the head, you run at him with the scythe.” Tom heard all this, and said:—

“Father! father! I am here. The wolf has swallowed me.”

“Heaven be praised!” said the woodman. “We have found our dear child again. Do not use the scythe, wife, for you may hurt him.” Then he aimed a great blow, and struck the wolf on the head, and killed him at once. They opened him, and set Tom Thumb free.

“Ah!” said his father, “what fears we have had for you!”

“Yes, father,” he answered. “I have traveled all over the world since we parted, and now I am very glad to get fresh air again.”

“Where have you been?”

“I have been in a mouse-hole, in a snail-shell, down a cow’s throat, and inside the wolf, and yet here I am again, safe and sound.”

“Well, well,” said his father. “We will not sell you again for all the riches in the world.”

So they hugged and kissed their dear little son, and gave him plenty to eat and drink. And they bought him new clothes, for his old ones had been quite spoiled on his journey.

A Hare once made fun of a Tortoise.

“What a slow way you have!” he said. “How you creep along!”

“Do I?” said the Tortoise. “Try a race with me, and I will beat you.”

“You only say that for fun,” said the Hare. “But come! I will race with you. Who will mark off the bounds, and give the prize?”

“Let us ask the Fox,” said the Tortoise.

The Fox was very wise and fair. He showed them where they were to start, and how far they were to run.

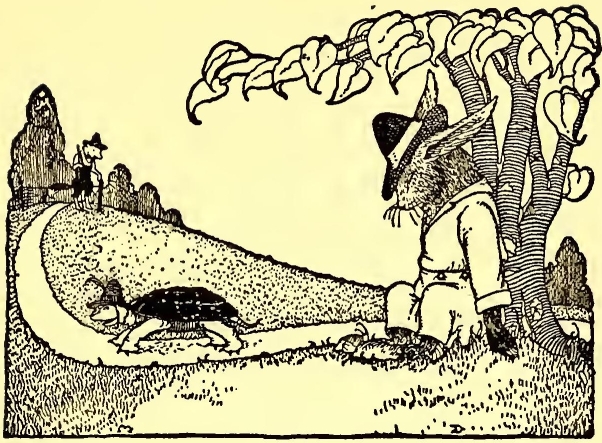

The Tortoise lost no time. She started at once, and jogged straight on.

The Hare knew he could come to the end in two or three jumps. So he lay down and took a nap first. By and by he awoke, and then ran fast. But when he came to the end, the Tortoise was already there!

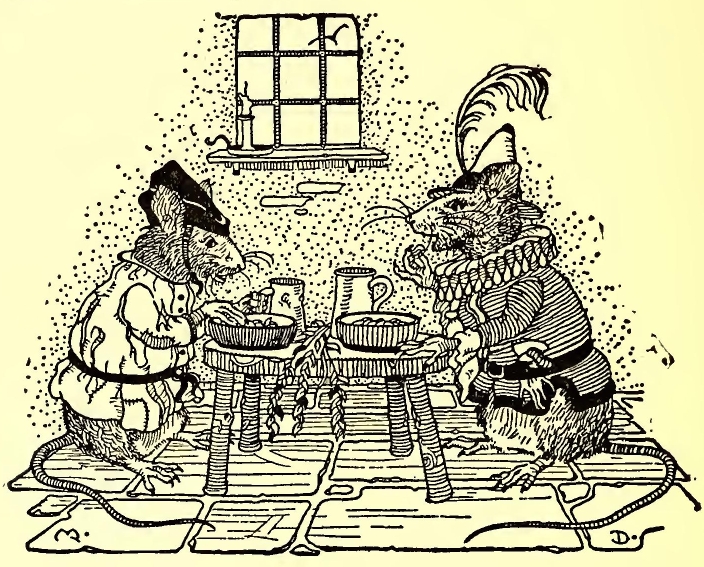

A Country Mouse had a friend who lived in a house in town. Now the Town Mouse was invited by the Country Mouse to take dinner with him. Out he went, and sat down to a dinner of barley and wheat.

“Do you know, my friend,” said he, “that you live a mere ant’s life out here? Now, I have plenty at home. Come and enjoy the good things there with me.”

So the two set off for town. There the Town Mouse showed the other his beans and meal, his dates, his cheese and fruit and honey.

As the Country Mouse ate, drank, and was merry, he praised his friend and bewailed his own poor lot.

But while they were urging each other to eat heartily, a man suddenly opened the door. Frightened by the noise, they crept into a crack. By and by, when he had gone, they came out and tasted of some dried figs. In came another person to get something that was in the room. When they caught sight of him, they ran and hid in a hole.

At that the Country Mouse forgot his hunger, and with a sigh, said to the other:—