THE HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT

THE HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Mother of Parliaments, by Harry Graham This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Mother of Parliaments Author: Harry Graham Release Date: November 6, 2012 [EBook #41304] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MOTHER OF PARLIAMENTS *** Produced by Mark C. Orton, Additional images were supplied by The Internet Archive. and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from scanned images of public domain material from the Google Print project.)

THE HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT

THE HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT

AUTHOR OF "A GROUP OF SCOTTISH WOMEN"

WITH TWENTY ILLUSTRATIONS

BOSTON

LITTLE, BROWN, & COMPANY

1911

TO

MY WIFE

The history of England's Parliament is the history of the English people. To the latter it must consequently prove a source of never-failing interest. That it does so is clearly shown by the long list of writers who have sought and found inspiration in the subject. To add to their number may perhaps seem an unnecessary, even a superfluous, task. This volume may indeed be likened to that "Old Piece in a New Dress" to which Petyt compared his Lex Parliamentaria. "These things, men will say, have been done before; the same Matter, and much the same Form, are to be found in other Writers, and this is but to obtrude upon the World a vain Repetition of other men's observations." But although the frank use of secondhand matter cannot in this case be denied, it is to be hoped that even the oldest and most threadbare material may be woven into a fresh pattern, suitable to modern taste.

In these democratic days a seat in either House of Parliament is no longer the monopoly of a single privileged class: it lies within the reach of all who can afford the luxury of representing either themselves or their fellows at Westminster. It is therefore only natural that the interest in parliamentary affairs should be more widely disseminated to-day than ever. It does not confine itself to actual or potential members of both Houses, but is to be found in the bosom of the humblest constituent, and even of that shadowy individual vaguely referred to as the Man in the Street. Though, however, the interest in Parliament is widespread, a knowledge of parliamentary forms, of the actual conduct of[vi] business in either House, of the working of the parliamentary machine, is less universal.

At the present time the sources of information open to the student of parliamentary history may roughly be regarded as twofold. For the earnest scholar, desirous of examining the basis and groundwork of the Constitution, the birth and growth of Parliament, the gradual extension and development of its power, its privileges and procedure, the writings of all the great English historians, and of such parliamentary experts as Hatsell, May, Palgrave, Sir William Anson, Sir Courtenay Ilbert and Professor Redlich, provide a rich mine of information. That more considerable section of the reading public which seeks to be entertained rather than instructed, can have its needs supplied by less technical but no less able parliamentary writers—Sir Henry W. Lucy, Mr. T. P. O'Connor, Mr. MacDonagh—none of whom, as a rule, attempts to do more than touch lightly upon fundamental Constitutional questions.

The idea of combining instruction with amusement is one from which every normal-minded being naturally shrinks: the attempt generally results in the failure either to inform or entertain. There does, however, seem to be room for a volume on the subject of Parliament which shall be sufficiently instructive to appeal to the student, and yet not so technical as to alarm or repel the general reader. It is with the object of supplying the need for such a book that the following pages have been written.

An endeavour to satisfy the tastes of every class of reader and at the same time to cover the whole field of parliamentary history within the limits of a single volume, must necessarily lead to many errors of admission as well as of omission. The material at the disposal of the author is so vast, and the difficulties of rejection and selection are equally formidable. Much of the information given must perforce be so familiar as to appear almost hackneyed. Many of the stories with which these pages are sprinkled bear upon them the imprint of extreme old age; they are grey with the cobwebs of[vii] antiquity. But while the epigram of the past is too often the commonplace of the present, the witty anecdote of one generation, which seems to another to plumb the uttermost abysses of fatuity, may yet survive to be considered a brilliant example of humour by a third. The reader, therefore, who recognises old favourites scattered here and there about the letterpress, will deride or tolerate them in accordance with the respect or contempt that he entertains for the antique.

I cannot lay claim to the possession of expert parliamentary knowledge, though perhaps, after close upon fifteen years' residence within the precincts of the Palace of Westminster, I may have acquired a certain intimacy with the life and habits of the Mother of Parliaments. For my facts I have to a great extent relied upon the researches of numerous parliamentary writers, past and present, to whom I have endeavoured to express my indebtedness, not only in copious footnotes, but also in the complete list of all sources of information given at the end of this volume. I wish to express my thanks to the many friends and acquaintances who have so kindly assisted me with their counsel and encouragement; to Mr. Kenyon, Mr. Sidney Colvin and the officials of the Print Room and Reading Room at the British Museum; to Sir Alfred Scott-Gatty, Garter King-at-Arms; to Mr. Edmund Gosse, Librarian of the House of Lords, and other officers of both Houses. My thanks are particularly due to Sir Henry Graham, Clerk of the Parliaments, who placed his unique parliamentary experience at my disposal, and whose invaluable advice and assistance have so greatly tended to lighten and facilitate my literary labours.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| PREFACE | v | |

| I. | PARLIAMENT AND PARTY | 1 |

| II. | THE HOUSE OF LORDS | 18 |

| III. | THE HOUSE OF COMMONS | 39 |

| IV. | THE PALACE OF WESTMINSTER | 60 |

| V. | HIS MAJESTY'S SERVANTS | 81 |

| VI. | THE LORD CHANCELLOR | 103 |

| VII. | THE SPEAKER | 119 |

| VIII. | THE OPENING OF PARLIAMENT | 135 |

| IX. | RULES OF DEBATE | 158 |

| X. | PARLIAMENTARY PRIVILEGE AND PUNISHMENT | 173 |

| XI. | PARLIAMENTARY DRESS AND DEPORTMENT | 189 |

| XII. | PARLIAMENTARY ELOQUENCE | 203 |

| XIII. | PARLIAMENT AT WORK (I.) | 225 |

| XIV. | PARLIAMENT AT WORK (II.) | 242 |

| XV. | STRANGERS IN PARLIAMENT | 259 |

| XVI. | PARLIAMENTARY REPORTING | 275 |

| SOURCES AND REFERENCES | 288 | |

| INDEX | 299 | |

| The Houses of Parliament | Frontispiece |

| From a Photograph by J. Valentine & Sons | |

| FACING | |

| PAGE | |

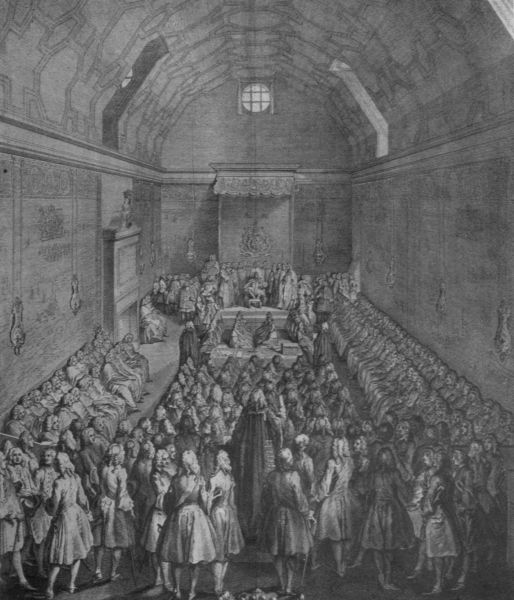

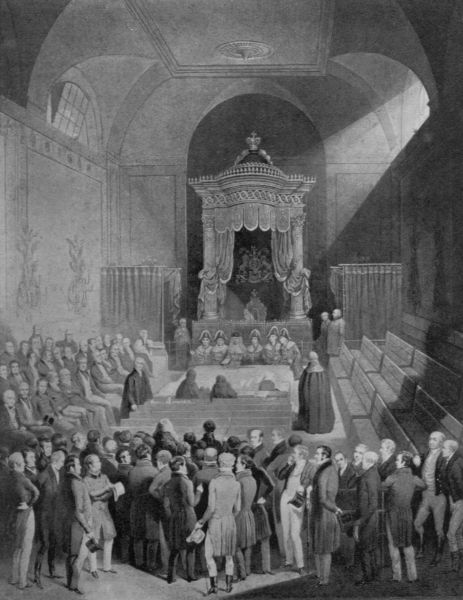

| The House of Lords in 1742 | 26 |

| From an Engraving by John Pine | |

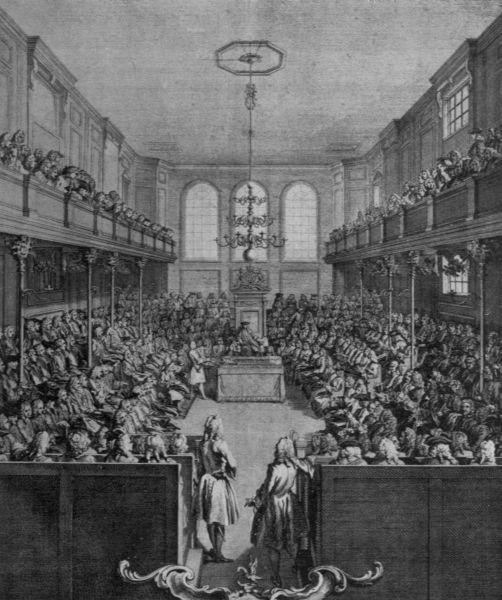

| The House of Commons in 1742 | 46 |

| From an Engraving by John Pine | |

| Westminster Hall in 1797 | 62 |

| From an Engraving by C. Mosley | |

| The Remains of St. Stephen's Chapel after the Fire of 1834 | 72 |

| From a Lithograph after the Drawing by John Taylor, Jr. | |

| Sir Robert Walpole | 84 |

| From the Painting by Francis Hayman, R.A., in the National Portrait Gallery | |

| Chatham | 92 |

| From the Painting by William Hoare, R.A., in the National Portrait Gallery | |

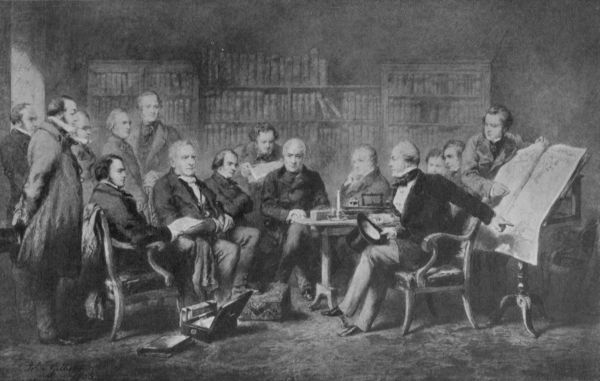

| A Cabinet Meeting (the Coalition Ministry of 1854) | 100 |

| From the Drawing by Sir John Gilbert | |

| Lord Eldon | 114 |

| From the Painting by Sir Thomas Lawrence, P.R.A., in the National Portrait Gallery | |

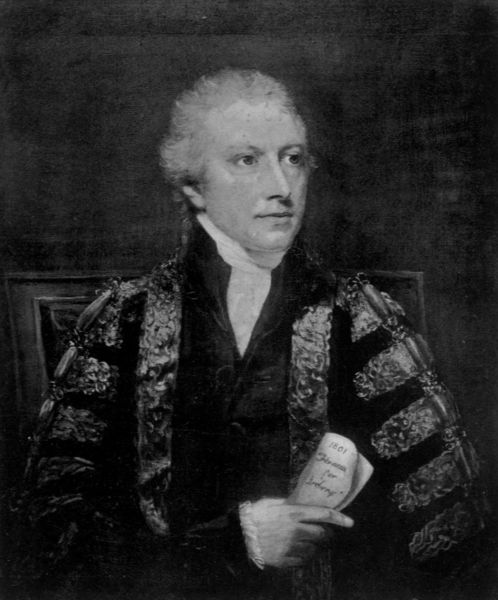

| Charles Abbot (Lord Colchester) | 124 |

| From the Painting by John Hoppner, R.A., in the National Portrait Gallery | |

| [xii] | |

| The Treasury Bench in 1863 | 138 |

| From an Engraving after the Painting by J. Philip | |

| The House of Commons in 1910 | 162 |

| From a Photograph by London Electrotype Agency | |

| The House of Commons in 1835 | 186 |

| From an Engraving by Samuel Cousins from the Painting by H. W. Burgess | |

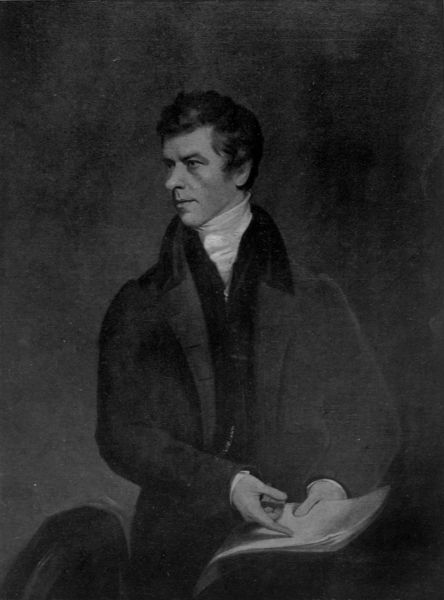

| Henry Brougham (Queen Caroline's Attorney-general, Afterwards Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain) | 194 |

| From the Painting by James Lonsdale in the National Portrait Gallery | |

| The House of Commons in Walpole's Day | 200 |

| From the Engraving by A. Fogg | |

| |

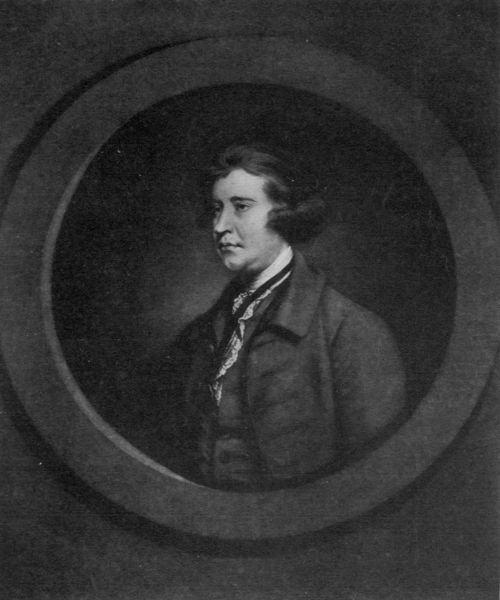

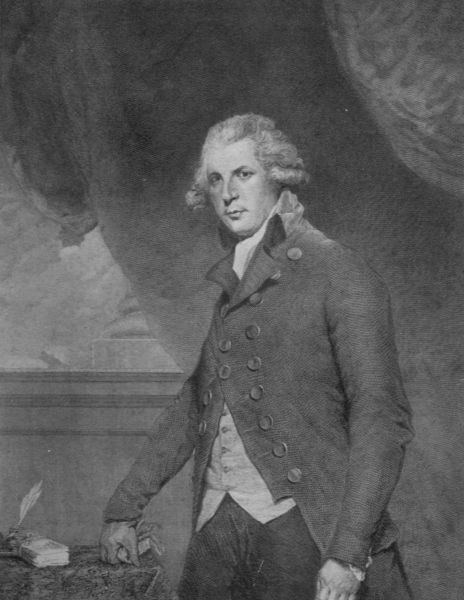

| Edmund Burke | 206 |

| From an Engraving by J. Watson after the Painting by Sir J. Reynolds | |

| Richard Brinsley Sheridan | 212 |

| From an Engraving by J. Hall after the Painting by Sir J. Reynolds | |

| The Passing of the Reform Bill in the House of Lords | 246 |

| From an Engraving after the Painting by Sir J. Reynolds | |

| The House of Lords in 1910 | 268 |

| From a Photograph by London Electrotype Agency | |

| William Woodfall | 284 |

| From the Painting by Thomas Beach in the National Portrait Gallery |

It has been asserted that the different social conditions of various peoples have their origin, not so much in climate or parentage, as in the character of their governments. If that be true, there is little doubt that the social conditions of England should compare most favourably with those of sister nations. But the admirable form of Government to which Englishmen have now long been accustomed, did not come into existence in the course of a single night. "The resemblance between the present Constitution and that from which it originally sprang," says an eighteenth-century writer, "is not much nearer than that between the most beautiful fly and the abject worm from which it arose."[1] And the conversion of the chrysalis into the butterfly has been a slow and troublesome process.

Montesquieu, who was an earnest student of the English Constitution, after reading the treatise of Tacitus on the manners of the early Germans, declared that it was from them that England had borrowed her idea of political government. Whether or no this "beautiful system was first invented in the woods,"[2] as he says, it is certain that we owe the primary principles of our existing constitution to German sources.[2] They date back to the earliest days of the first settlements of Teutons on the Kentish shores.

To the word "parliament" many derivations have been assigned. Petyt explains the name as suggesting that every member of the assembly which it designates should parler le ment or speak his mind.[3] Another authority derives it from two Celtic words, signifying to "speak abundantly"—a meaning which is more applicable in these garrulous times than it was in days when debate was often punctuated by lengthy intervals of complete silence.

Whatever its derivation, the word no doubt referred originally to the "deep speech" which the kings of old held with their councillors. The first mention of it, in connexion with a national assembly, occurs in 1246, when it was used by Matthew Prior of a general convocation of English barons. About thirty years later it appears again in the preamble to the First Statute of Westminster. It has now come to be employed entirely to describe that combination of the Three Estates, the Lords Spiritual, the Lords Temporal and the Commons, which with the Crown form the supreme legislative government of the country.

The ancient Britons possessed a Parliament of a kind, called the Commune Concilium. Under the Heptarchy each king in England enjoyed the services of an assembly of wise men—or Witenagemot, as it was called—which advised him upon matters of national importance. The Witan sat as a court of justice, formed the Council of the chiefs, and could impose taxes and even depose the King, though the latter too often took the whole of their powers into his own hands. When the separate kingdoms became united, their different Councils were absorbed into the one great Gemot of Wessex. This, in Anglo-Saxon times, was a small body, consisting of less than a score of Bishops, a number of Ealdormen (or heads of the different shires), and certain vassal members. This senate was undoubtedly the germ of all future systems of Parliamentary government; and though for the first two[3] hundred years after the Conquest there is no historical record of the meeting of any body corresponding to our present Parliament, from the days of the Witenagemot to our own times the continuity of our national assemblies has never been broken.

The parliamentary historian suffers much from the lack of early records. None were kept in Anglo-Saxon times, the judgments of the Witan being only recorded in the memory of the judges themselves. The Rolls of Parliament begin with the year 1278—though the first mention of the Commons does not occur until 1304—and somewhere about Edward III.'s reign was written a volume called the "Vetus Codex" or "Black Book" which contains transcripts of various parliamentary proceedings. At the time of the restoration of Charles II., Prynne, the antiquarian, set himself the task of exhuming old records, and catalogued nearly a hundred parcels of ancient writs, private petitions, and returns. The MSS. which he worked upon were so dirty that he could not induce any one else to clean them, and was forced to labour alone. Wearing a nightcap over his eyes, to keep out the dust, and fortified by continual draughts of ale, he proceeded cheerfully with this laborious undertaking upon which he finally based the book which has made him famous.[4]

The House of Commons Journals begin with Edward VI. those of the Lords at the accession of Henry VIII. And though during the early part of the seventeenth century speeches were reported at some length in the Commons Journals, in the Lords only the Bills read and such matters are recorded.[5] The material to work upon is consequently of an exiguous nature, until we reach the later days of freedom of the Press and publicity of debates.

The history of Parliament proper divides itself naturally into four distinct periods. The first may be said to stretch[4] from the middle of the thirteenth to nearly the end of the fifteenth century; the second dates from the accession of Henry VII., and extends to the Revolution of 1688. The remaining century and a half, up to the Reform Bill of 1832, forms the third period; and with the passing of that momentous Act commences the last and most important epoch of all.

During the first two periods of parliamentary history, the whole authority of government was vested in the Crown; during the third it gradually passed into the possession of the aristocracy: and it is only within the last century that the people, through their representatives in the House of Commons, have gained a complete political ascendency.

From the days of the absolute monarchy of Norman sovereigns until the reign of King John, the Crown, the Church, the Barons, and the people, were always struggling with each other; in that reign the three last forces combined against the King. The struggle was never subsequently relaxed, but it took over six centuries to transfer the governing power of the country from the hands of one individual to that of the whole people.

Prior to the reign of Henry III., no regular legislative assembly existed, though the King would occasionally summon councils of the great men of the land for consultative purposes. In William the Conqueror's time the ownership of land became the qualification for the Witenagemot, and the National Council which succeeded that assembly thus became a Council of the King's feudal vassals, and not necessarily an assembly of wise men. When, however, Simon de Montford overthrew Henry III. at Lewes, he summoned a convocation which included representative knights and burgesses, and the parliamentary system, thus instituted, was subsequently adopted by Edward I. "Many things have changed," says Dr. Gardiner in his "History of England," "but in all main points the Parliament of England, as it exists at this day, is the same as that which gathered around the great Plantagenet." The first full Parliament in English history[5] may, therefore, be said to have been summoned by Edward I. on November 13, 1295, and represented every class of the people.

Parliament thereafter gradually resolved itself into two separate groups; on the one hand the barons and prelates, representing the aristocracy and the Church, on the other the knights and burgesses, representing the county freeholders, citizens and boroughfolk. The former constituted a High Court of Justice and final Court of Appeal; the chief duty of the latter lay in levying taxes, and they were not usually summoned unless the Crown were in need of money. These two component groups originally sat together, forming a collective assembly from which the modern Parliament has gradually developed.

In the early days of Parliament the Lords came to be regarded as the King's Council, over which he presided in person; the Commons occupied a secondary and insignificant position. The power of legislating was entirely in the hands of the King, who framed whatever laws he deemed expedient, acting on the humble petition of his people. The Crown thus exercised absolute control over Parliament, and the royal yoke was not destined to be thrown off for many hundreds of years.

In the reign of Edward III., the meetings of Parliament were uncertain and infrequent; its duration was brief. Three or four Parliaments would be held every year, and only sat for a few weeks at a time. The King's prerogative to dissolve Parliament whenever he so desired—"of all trusts vested in his majesty," as Burke says, "the most critical and delicate"[6] was one of which mediæval monarchs freely availed themselves in the days when Parliament had not yet found, nor indeed realised, its potential strength.

During the reigns of the Tudors and Stuarts, the power of the Crown was still supreme, though many attempts were[6] made to weaken it. This second period of history, between 1485 and 1688, was a time of peculiar political stress, in which Parliament and the Crown were engaged in a perpetual conflict. Kings maintained their influence by a mixture of threats and cajolery which long proved effective. In 1536, for instance, we find Henry VIII. warning the House of Commons that, unless some measure in which he was interested were passed, certain members of that assembly would undoubtedly lose their heads.[7]

The Stuart kings were in the habit of suborning members of both Houses, by the gift of various lucrative posts or the lavish distribution of bribes. It was ever the royal desire to weaken Parliament, and this end was attained in a variety of ways. In the early part of the seventeenth century, we hear of Charles I. summoning to Hampton Court certain members whose loyalty he distrusted or whose absence from Parliament he desired. On one such occasion the Earls of Essex and Holland refused to obey his command, saying that their parliamentary writ had precedence of any royal summons—an expression of independence for which they were dismissed from the Court.[8]

In the time of Charles II. a definite system of influencing members of Parliament by gifts of money was first framed, Lord Clifford, the Lord Treasurer, being allowed a sum of £10,000 for the purpose. The fact of holding an appointment in the pay of the Crown was in itself considered sufficient to bind a member to vote in accordance with the royal will. In 1685, when many members who were in the Government service threatened to vote against the Court, Middleton, the Secretary of State, bitterly reproached them with breach of faith. "Have you not a troop of horse in his Majesty's service?" he asked of a certain Captain Kendall. "Yes, my lord," was the reply, "but my brother died last night and left me £700 a year!"[9]

Andrew Marvell has drawn a vivid but disagreeable picture of the Parliament which was summoned immediately after the Restoration. Half the members of the House of Commons he described as "court cullies"—the word "to cully" meaning apparently to befool or cheat—and in "A list of the Principal Labourers in the great Design of Popery and Arbitrary Law," gives a catalogue of the names of over two hundred members of Parliament who received presents from the Court at this time.[10]

The independence of Parliament was first asserted by that staunch old patriot Sir John Eliot, who, during the reign of Charles I., declared to the Commons that they "came not thither either to do what the King should command them, nor to abstain when he forbade them; they came to continue constant, and to maintain their privileges."[11] But in spite of such brave words, the power of the Crown was not finally subdued until the Revolution.

The downfall of the Monarchy at the time of the Commonwealth was followed by the temporary abolition of both Lords and Commons, the latter disappearing in company with Cromwell's famous "bauble." The Protector then proceeded to call together a body of "nominees," one hundred and forty in number, who represented the various counties in proportion to the amount of taxes each of these contributed. Of the seven nominees supplied by London, Praise God Barebones, a Fleet Street leather merchant, gave his name to the Parliament thus assembled. Cromwell also created a new House of Lords, numbering about sixty.[12]

With the Restoration the Crown resumed much of its former power. In 1682 the publisher of a reprint of Nathaniel Bacon's "Historical Discourse," which declared that Kings could "do nothing as Kings but that of Right they ought to do," and that though they might be "Chief Commanders, yet they are not Chief Rulers," was outlawed for these treasonable statements. It was not, indeed, until the Revolution of 1688 that the royal influence was curtailed, so small a revenue being allowed to William III. that the ordinary expenses of government could not be defrayed without assembling Parliament.

The attendance of the King in Parliament had been usual in early days, but the Commons always deprecated the presence of the Sovereign in their midst. Charles I. affords the only example of a monarch attending a debate in the Lower House, when on that famous 4th of January, 1642, he marched from Whitehall to Westminster, with the intention of arresting the five leading members, Hampden, Pym, Holles, Haselrig and Strode, authors of the Grand Remonstrance, whom he had caused to be impeached on the preceding afternoon. The House had been put upon its guard by Lady Carlisle, and on the eventful day, a French officer, Hercule Langres, made his way to Westminster and warned Pym and his colleagues of the approach of the royal troops. When therefore the King arrived he found that his birds had already flown, and was compelled to retire empty-handed, amid cries of "Privilege!" from members of the outraged assembly.

In those times the desire of the Commons was to keep the Crown as ignorant as possible on the subject of their doings. The habit of providing the King with a daily account of Parliamentary proceedings did not come into fashion until the end of the eighteenth century, when the House was no longer afraid of the royal power.

The Lords have never objected as strongly as the[9] Commons to the royal presence. Charles II. often found the time hang heavy on his hands, and would stroll down to the Upper House, "as a pleasant diversion." He began by sitting quietly on the Throne, listening to the debates. Later on he took to standing by the fireplace of the Lords, where he was soon surrounded by many persons anxious to gain the royal ear, and thus "broke all the decency of that House."[13] Since the accession of Queen Anne, however, no Sovereign has been present in Parliament, save at the opening or closing ceremonies. But long after kings had ceased to attend Parliament in person they continued to attempt the control of its proceedings. George III. finally brought matters to a head by his perpetual interference with the affairs of the Commons, and caused the passing of that momentous resolution, moved by Dunning on April 6, 1780, "that the influence of the Crown has increased, is increasing, and ought to be diminished," which disturbed if it could not vex Dr. Johnson.[14]

Between 1688 and 1832 political life in England was excessively corrupt. Parliament had grown to a certain extent independent of the Crown, but had not yet learnt to depend upon public opinion. It was consequently a difficult body to deal with, and had to be managed by a system of open bribery which first showed itself most conspicuously in the shape of retaining fees paid to Scottish members.[15] In 1690 the practice of regularly bribing members of the House of Commons was undertaken by the Speaker, Sir John Trevor, on behalf of the Tory party. In Queen Anne's reign a statesman paid thousands of pounds for the privilege of being made Secretary of State, and a few years[10] later we find Sir Robert Walpole assuring a brother of Lord Gower that he knew the price of every man but three in the House of Lords.[16]

Bribery no longer emanated direct from the Crown, but was practised vicariously by the King through his ministers. They might object to the system, but, as King William once said to Bishop Burnet, they had to do with "a set of men who must be managed in this vile way or not at all."[17] Macaulay likens the Parliament of that time to a pump which, though it may appear dry, will, if a little water is poured into it, produce a great flow. So, he says, £10,000 given in bribes to Parliament would often produce a million in supplies.[18] Even Pelham, a man of unblemished reputation in private life, saw the absolute necessity of distributing bribes right and left. And in 1782 we find Lord North writing to George III. to remind him that "the last general election cost near £50,000 to the Crown, beyond which expense there was a pension of £1000 a year to Lord Montacute and £500 a year to Mr. Selwyn for their interest at Midhurst and Luggershall."[19]

Seats in Parliament were regularly bought and sold, the price varying from £1500 to as much as £7000. Flood, the Irish politician, purchased a seat in the English House of Commons for £4000. The notoriously corrupt borough of Gatton was publicly advertised for sale in 1792, with the power of nominating two representatives for ever, described by the auctioneer as "an elegant contingency."[20] This same seat was sold in 1831 by Sir Mark Wood for the huge sum of £60,000, and the purchaser's feelings may well be imagined when, under the Reform Act of the following year, the borough was disfranchised and rendered worthless.[21]

Parliament was for long in the hands of a few rich persons. Wealthy individuals would buy property in small boroughs in order to increase their political influence, and cared little for the fitness of the representatives whom they nominated. The story is told of a peer being asked who should be returned for one of his boroughs, and casually mentioning a waiter at White's Club whom he did not even know by name. The waiter was duly elected, and, for aught we know, may have made a most worthy and excellent member of Parliament.[22]

In 1815 the House of Commons contained 471 members who were the creatures of 144 peers and 123 Commoners. Sixteen representatives were Government nominees; and only 171 members were actually elected by the popular vote.[23] Five years later nearly half the House were returned by peers.[24]

The passing of the Septennial Act in 1716, in place of the Triennial Act of 1694, though meeting with much hostile criticism,[25] had helped to further that growing independence of both Lords and Crown which was the chief aim of the Commons. Before the Triennial Act Parliament could only be dissolved by the Crown. Under the Triennial Act it suffered a natural death three years after the day on which it was summoned. The Septennial Act lengthened that existence by a further period of four years. Members were no longer kept in a state of perpetual anticipation of an imminent General Election; they were no more harassed by the fear of losing their seats at any moment. With security came strength, but purity was a long time in following. The Septennial Act, says Lecky, gave "a new stability to English policy, a new strength to the dynasty, and a new authority to[12] the House of Commons." But it certainly did not tend to decrease the corruption which was then rampant both in Parliament and in the country.

The whole body politic was, indeed, utterly rotten, and it was only considered possible to maintain the ministerial influence by a system of disciplined Treasury corruption. The secret service money with which votes were bought was in the control of the Prime Minister, and Walpole is said to have stated that he did not care a rap who made Members of Parliament so long as he was allowed to deal with them after they were made. The produce of the taxes descended in fertilizing showers upon the proprietors, the agents and the members for boroughs. For them, as Lord John Russell said, the General Election was a state lottery in which there was nothing but prizes. "The elector of a borough, or a person he recommends, obtains a situation in the Customs; the member of Parliament obtains a place in the Mediterranean for a near relation; the proprietor of the borough obtains a peerage in perspective; and the larger proprietor, followed by his attendant members, shines in the summer of royal favour, with a garter, a regiment, an earldom, or a marquisate."[26] So ingrained had this idea become in the public mind that the Duke of Wellington is supposed to have asked ingenuously, on the abolition of the rotten boroughs, "How will the King's Government be carried on?"

Several ineffectual efforts had from time to time been made to slay the monster of corruption. From the days of Cromwell the question of Parliamentary reform had been anxiously urged by many statesmen, notably Lord Shaftesbury and Pitt, of whom the latter introduced reformative measures in 1781, 1782 and 1785. But though Pitt, the first Prime Minister who did not retain any of the public money for distribution among his friends and supporters, managed to reduce "places" worth over £200,000, after the American War, there still remained any number of inflated pensions[13] and sinecures in the gift of the Government,[27] and it was not until Parliament came to be controlled entirely by public opinion that the change from corruption to purity took place. But notwithstanding many flaws in theory and blots in practice, the English Parliamentary Constitution prior to the Reform Bill was, as Mr. Gladstone called it, one of the wonders of the world. "Time was its parent, silence was its nurse.... It did much evil and it left much good undone; but it either led or did not lag behind the national feeling and opinion."[28] With the Reform Act of 1832, Parliament advanced another stage in its career. The House of Commons definitely shook itself free from the active corruption which had so long impeded its movements.

The principle of Party Government, which now lies at the very root of our parliamentary system, had its origin during the second period of parliamentary history, and formed no part of the constitutional scheme of earlier days.

In Queen Elizabeth's time two definite and distinct parties arose, the one maintaining the privileges of the Crown, the other upholding the interests of the people. In Stuart days Cavaliers and Roundheads were followed by Court and Country Parties, and in the year 1679, when the Exclusion Bill was being bitterly debated, the distinctive names of "Whigs" and "Tories" first came into existence. "Whig" was originally a word applied to the lowland peasantry of the West of Scotland; thence it came to mean Covenanters, and so politicians who looked kindly upon Nonconformity. "Tory" was an expression popularly used with reference to the rebel Irish outlaws who harassed the Protestants; and thus implied leanings towards Catholicism.[29]

The growth of a respect for the people's rights forced[14] politicians to separate into two sections, and the schism between the rival camps was still further emphasized by the Revolution of 1688. Regular opposing parties do not, however, seem to have existed in the Commons until the eighteenth century, and the party system was not finally established as a necessary element of constitutional government until the reign of William III. Kings had hitherto chosen their advisers irrespective of their political views. William III. was, however, induced by the Earl of Sunderland to form a Ministry from the party that held a majority in Parliament, and thus became to a certain extent controlled by that party.

There have always been, as Macaulay says, under some name or other, two sets of men, those who are before their age, and those who are behind it, those who are the wisest among their contemporaries, and those who glory in being no wiser than their great-grandfathers. But this definition of the two great political parties of England can no longer with justice be applied. The Tory of to-day is not at all the Tory of two hundred years ago: indeed, he rather resembles the Whig of Queen Anne's time. And though Disraeli continued to use the word "Tory," and was never ashamed of it, it has now gradually fallen into disuse, save as a term of reproach on the lips of political opponents. A change of nomenclature was adopted in 1832. The Tories became Conservatives, and for the benefit of wavering Whigs it was proposed that the latter should be known as Liberal-Conservatives, a name which, as Lord John Russell remarked, expressed in seven syllables what Whig expressed in one.[30] The term "Radical" did not come into use until the days of the famous reformer, Francis Place (1771-1854); his political predecessors contenting themselves with the more modest name of Patriots.[15] Called by whatever name is popular for the moment, either party may now claim to come within the scope of Burke's well-known definition as "a body of men united for promoting, by their endeavours, the national interest upon some particular principle in which they are all agreed."

Our modern parliamentary system comprises the party spirit as its most vital element, and owes its success to the fact of being government by party and not by faction.[31] The existence of an admittedly constitutional body perpetually opposed to the Government of the day—"His Majesty's Opposition," as it has been called since 1826—is now recognised as a very necessary portion of the Parliamentary machine. The principle of fairness to the minority is never lost sight of, and expresses itself in many different ways. When, for instance, the Leader of the Opposition gives notice of a motion of censure on the Government, the latter consider it their duty to accord their critics an early opportunity for its discussion; and, generally speaking, the due consideration of the rights of minorities is among the primary instincts of party government. The excellent effects of this system are obvious. Of the two ways of obtaining political adherents the attachment of party is infinitely preferable to the attachment of personal interest, formerly so prolific a source of corruption. Party feeling may also be said to have created general rules of politics, similar to a general code of morals by which a man may "walk with integrity along the path chosen by his chiefs, surrounded and supported by his political colleagues."

Opposition is invaluable as providing a stern criticism of the Government's policy; it can also very often be of service to the cause it is intended to injure. It excites a keener public curiosity, by directing attention to the motives of those whom it suspects. And "the reproaches of enemies when refuted are a surer proof of virtue than the panegyrics[16] of friends."[32] That the system must possess certain disadvantages is inevitable. It no doubt engenders animosity and provokes violent contentions: it stimulates politicians to impute to their opponents corrupt motives which they could not for a moment imagine themselves capable of entertaining. It may also on occasion tempt them to continue obstinately in the support of wrong, because the admission of a mistake would be hailed as a triumph for their enemies. "The best cause in the world may be conducted into Faction," as Speaker Onslow said; "and the best men may become party men, to whom all things appear lawful, which make for their cause or their associates."[33] But as a rule the game of politics is played with commendable fairness and an absence of undue acrimony. The Opposition, whose well-known duty it is "to oppose everything, to propose nothing, and to turn out the Government,"[34] rarely makes its attacks the vehicle for personal spite. Politicians of adverse views do not carry their antagonism into private life, and off the stage of Parliament the bitterest opponents are able to exist upon amicable terms. Occasionally, however, political differences have been the cause of ruptured friendship. When Burke made a violent attack upon Fox, in 1791, on the Canada Bill, he declared that if necessary he would risk the latter's lifelong friendship by his firm and steady adherence to the British Constitution. Fox leaned across and whispered that there was no loss of friends. "Yes," replied Burke, "there is a loss of friends. I know the price of my conduct. I have done my duty at the price of my friend. Our friendship is at an[17] end!" So terminated an intimacy of twenty-five years' standing. Such an incident may, nevertheless, be considered exceptional, the relations of antagonists being usually of a most harmonious kind. Sir Robert Peel and Lord John Russell would often be seen together engaged in friendly conversation. O'Connell once walked arm in arm down Whitehall with Hughes Hughes, the member for Oxford, whose head he had but recently likened to that of a calf.[35] And the present Prime Minister and Leader of the Opposition are doubtless able to play bridge or golf together without actually coming to blows. In spite, therefore, of much criticism, what Emerson calls "that capital invention of freedom, a constitutional opposition,"[36] has been found to be the most practical and satisfactory means of carrying on government.

No constitutional principle has been so strongly criticised and so freely abused as the one embodied in the hereditary chamber which forms so important a branch of our legislature. Pulteney labelled the House of Lords a "hospital for invalids"; Burke contemptuously referred to it as "the weakest part of the Constitution"; Lord Rosebery has compared it to "a mediæval barque stranded in the tideway of the nineteenth century." A more democratic modern statesman, who doubtless hopes—

has declared the only legislative qualifications of peers to consist in their being the first-born of persons possessing as little qualifications as themselves. While another politician cynically observes that they represent nobody but themselves, and enjoy the full confidence of their constituents.

The House of Lords has long been the butt of the political satirist, and parliamentary reformers have attacked it for years patiently and persistently, hitherto without much success. "We owe the English Peerage to three sources," said a character in "Coningsby"; "the spoliation of the Church; the open and flagrant sale of its honours by the elder Stuarts; and the borough-mongering of our own times." And this bitter criticism is often quoted to prove the weakness of any form of hereditary government.

The suggestion that heredity can confer any peculiar qualifications, rendering a person more fit than his fellows for[19] parliamentary power, is no doubt illogical, but not more so perhaps than a thousand other ideas which govern the affairs of men. The form of government by majority, for instance,—which Pope called "the madness of the many for the gain of a few"—is obviously open to criticism. Hereditary legislation has, at any rate in the eyes of its supporters, the merit of having answered well enough in practice, and, however theoretically indefensible, is not more so than hereditary kingship. The Sovereign does not inherit sagacity any more than the Duke of Norfolk, as Lord John Russell justly observed, and it would be unwise as well as unsafe to hang the Crown on the peg of an exception. It is as well, however, to remember that the Sovereign is a constitutional monarch whose powers nowadays are much restricted, whereas the Lords have the right to exercise a legislative veto the use of which kings have long since resigned.

Talent is not hereditary. No man chooses a coachman, as the first Lord Halifax once remarked, because his father was a coachman before him. But the descendant of a long line of coachmen is likely to know more about the care of horses than the grandson of a pork butcher, however eminent; and the scion of a race of legislators is at least as fully qualified for the duties of a legislator as many a politician whose chief reason for entering Parliament is the desire to add the letters M.P. to his name. Nevertheless, as has been recently pointed out by tactless statisticians, the great men of the past have but seldom bequeathed their admirable qualities to their eldest sons, and in a list of modern statesmen will be found but few of the names once famous in English history.

The necessity for a second chamber of some sort has always been admitted, if only to prevent the other House from being exposed to what John Stuart Mill calls "the corrupting influence of undivided power," and Cromwell "the horridest arbitrariness that was ever known in the world." Few, however, of the most ardent admirers of the hereditary system will pretend that the problem of a perfect bicameral system is solved by the present House of Lords, though they[20] may doubtless claim that the cause of its failure does not rest entirely upon its basis of heredity. "You might as well urge as an objection to the breakwater that stems the unruly waves of the sea, that it has its foundations deep laid in another element, and that it does not float on the surface of that which it is to control," said Palmerston, "as say that the House of Lords, being hereditary, ought on that account to be reformed."[37]

If age can confer dignity and distinction upon any assembly, then must the House of Lords be peculiarly distinguished, for it is certainly the most venerable as well as the most antiquated of our Parliamentary institutions.

When Christianity became firmly established in England, each king of the Heptarchy was attended by a bishop, whose business it was to advise his royal master upon religious questions, and who thus acquired the power of influencing him in other matters as well. The minor kings were gradually replaced by earls, who were summoned, together with their attendant bishops, to the Witenagemot of the one ruling sovereign of the country. An assembly of this nature was held as far back as 1086, but it was more in the nature of a judicial Court than a Parliament. It consisted of the Archbishop of Canterbury and all other bishops, earls, and barons, and was summoned to decide important judicial cases. This Court, or Curia Regis as it was called, met at different times and in divers places. It transacted other business besides the judicial, and also corresponded to some extent with the more modern levée. It was originally composed of the Lords, the great officers of State, and some others whom the king wished to consult.

The exact position which such nobles held in the great Council of the land is not very definite. Immediately after the Conquest an earldom appears to have been regarded as an office; but it was not necessarily hereditary. Later on the possession of lands, either granted direct by the Crown[21] or inherited, became a necessary qualification for the holder of an earldom. The transfer of titles and property in early days was a rough and ready affair, in which might played as great a part as right. (When Edward I. required the old Earl de Warrenne to produce his title deeds, the latter brought out a rusty sword that had belonged to his ancestors. "By this instrument do I hold my lands," he said, "and by the same do I intend to defend them!") But with the natural idea of the transference of land from father to son there developed the principle of the natural hereditary descent of the title dependent upon the possession of those lands.

The baronage did not come into existence until after the Conquest. In the reign of Henry I. it was entirely composed of foreigners from France. Barons held no regular office, but their lands were transferred on the hereditary principle. They owed military allegiance to the Crown, but did not necessarily sit in Parliament unless summoned to attend by the king. Such a summons was long regarded as a burden rather than a privilege, and even in the days of King John the barons only desired it as a protection from the imposition of some exceptional tax. The bishops and barons were then the natural leaders of the people; they alone were educated and armed, and they alone could attempt any successful resistance to the exorbitant demands of the Crown. They paid nearly all the taxes, and provided money for the prosecution of every war. Upon them the commonalty was dependent, looking to them for assistance when the sovereign became too grasping or tyrannical. It was the barons who forced King John to sign Magna Charta, and to them, therefore, we are indebted for the laws and constitution which we now possess. "They did not confine it to themselves alone," as Chatham declared in the House of Lords, on January 9, 1770, "but delivered it as a common blessing to the whole people." But though the present House of Lords has been described as composed of descendants of the men who wrung the Charter from King John on the plains of Runnymede, not more than four of the[22] existing peerages are, as a matter of fact, as old as Magna Charta.

The feudal barons by tenure, whose right to a Parliamentary summons gradually became hereditary as going with their lands, were gradually joined by other prominent men who, though not landowners, were summoned to give the Council the benefit of their experience and advice. Thus gradually evolved the modern system of hereditary legislators, and the House of Lords developed into an assembly such as we now know it, though numerically far smaller.

In Richard II.'s reign the Curia Regis separated from Parliament and became a Privy Council. The Lords were then as unwilling as the Commons to attend diligently to their Parliamentary duties, and it was only the subsequent creation of dukes, marquesses, and viscounts that stimulated the desire to sit and claim a writ of summons as a right.

The number of earls and barons summoned to Parliament in the reigns of the first three Edwards varied from fifty to seventy-five. At times, owing to the absence of the fighting men of the country who were engaged in foreign warfare, it fell as low as sixteen. In the first Parliament of Henry VIII. there were less than thirty temporal peers, but in Elizabeth's time this number had doubled. Since Stuart days the Lords have become more and more numerous. James I. granted peerages right and left to his favourites, and, by selling baronies, viscountcies, and earldoms for sums ranging from £10,000 to £20,000, enriched his coffers and added some fifty members to the Upper House. The eighty-two temporal peers who sat in his first Parliament were gradually reinforced by his successors, until, in the time of George III., they numbered two hundred and twenty-four, exclusive of their ecclesiastical brethren.

The Lords spiritual have not always sat in the House of Lords. In early days the abbots and priors largely predominated in that assembly, but with the abolition of the monasteries they were banished from it, though a certain[23] number retained their seats in right of the baronies which they possessed.[38] Bishops were excluded from the House of Lords by Act of Parliament in 1640—Cromwell omitted to summon them to his Upper House in 1657—and were not finally readmitted until 1661. Within living memory several unsuccessful attempts have been made to keep them out of Parliament. In 1836 a member of the Commons moved that spiritual peers be released from attendance, but his motion was defeated. Another member in the following year suggested their exclusion on the ground that they had plenty to occupy them elsewhere, that their contributions to debate upon most legislative subjects were not particularly edifying, and that they always voted with the Minister to whom they were indebted for preferment. This motion met a fate similar to that of its predecessor, as did another of the same kind in 1870.

To-day some twenty-six spiritual peers, including the two Archbishops of Canterbury and York, are given seats in the House of Lords, where they help to swell the number of that ever-increasing assembly.

Bishops usually confine themselves exclusively in the House of Lords to the discussion of matters which concern the spiritual welfare of the nation. Their contributions to debates are generally "edifying," and when they happen to cross swords with their lay brethren they are well able to hold their own. Bishop Atterbury, of Rochester, once said of a Bill before the House that he had often prophesied that such a measure would be brought up, and was sorry to find himself a true prophet. Lord Coningsby retorted that the Right Reverend Prelate had put himself forward as a prophet, but he would only liken him to a Balaam, who was[24] reproved by his own ass. The Bishop at once replied that he was well content to be compared to Balaam. "But, my Lords," he added, "I am at a loss to make out the other part of the parallel. I am sure that I have been reproved by nobody but his Lordship!"[39]

With the creation of new peerages by successive monarchs the list of temporal peers lengthened year by year. The Union of the three kingdoms still further added to their number. By the Acts of Union with Scotland and Ireland it was laid down that sixteen Scottish and twenty-eight Irish representative peers should sit in the House of Lords. These were to be elected by their fellow-peers, the former for each Parliament, the latter for life.[40] They may be distinguished in other particulars as well, for though a Scottish peer can at any time resign his seat, an Irish peer can never do so. Even though he be a lunatic, or otherwise incapable of attending, he still retains his place in the legislature. He is also privileged in other ways. In 1699 the Commons resolved that no peer could give his vote at the election of a Member of Parliament, and, three years later, that he could not interfere in elections. To-day a standing order of the House of Commons imposes the same restraint upon all but Irish peers, who are exempt from these restrictions.

In 1875 the House of Lords was strengthened judicially by the introduction of four Lords of Appeal. The House, as[25] is well known, has judicial as well as legislative functions to perform. It has always been the Supreme Court of the realm, and, ever since the reign of Queen Elizabeth, the ultimate Appeal has lain to it in all cases except those arising in Ecclesiastical Courts. Moreover, as the High Court of Parliament, in conjunction with the Commons, it is empowered to try offenders against the State whom the Commons have impeached. It also enjoys the privilege of trying any of its own members who may be charged with treason or felony, and of determining any disputed claims of peerage which may arise.

There have always been a sufficient number of Lords learned in the law to provide a court for the trial of legal cases. In the past, however, occasions have arisen when the presence of lay peers has threatened to replace the judicial aspect of the House by a political one which would be fatal to its reputation as a court of appeal. It was not, indeed, until 1845 that lords unlearned in the law began to consider their presence during the hearing of judicial causes to be not only unnecessary but undesirable, and discontinued their attendance. Thirty years later the institution of four life peerages, conferred upon eminent lawyers, added still further weight to the legal decisions of the House. The hearing of appeals is now left entirely to what are called the Law Lords, who consist of the Lord Chancellor, a number of peers who have held certain high judicial offices, and the four Lords of Appeal in Ordinary—three of whom must, by the Appellate Jurisdiction Act of 1876, be present on all appeal cases.

The granting of life peerages, conferring rights of summons to the House of Lords, save as above stated, has been adjudged to be beyond the powers of the Crown. It may truly be said that in the first days of Parliament the House of Lords consisted almost entirely of life members. But when the Government of Queen Victoria attempted to revive a practice that had lain in abeyance for some centuries they were not allowed to do so.

[26]The Supreme Court of Appeal had been violently attacked in the Commons, where certain members declared it to be inferior to any tribunal in the land. Palmerston in 1856 determined to remedy its defects by the addition of two Law Lords who should be life peers. This scheme was upheld by the Lord Chancellor, Lord Cranworth, but met with determined opposition in the Upper House. The Law Lords were especially opposed to it, fearing that, if such a precedent were allowed, no lawyer in the future would ever be given an hereditary peerage. On the Premier's recommendation the Queen proposed to confer life peerages upon two distinguished lawyers, Parke and Pemberton Leigh, and proceeded to issue a patent to the former, creating him Baron Wensleydale for life. When, however, the matter was referred to the Committee for Privileges, they decided that no life peer could either sit or vote in the House of Lords, and the Wensleydale and Kingsdown peerages had consequently to be made hereditary.

Persons who are raised to the peerage to-day are made peers of the United Kingdom. No Scotch peer has been created since the Union in 1707, and the right of conferring an Irish peerage which existed under certain restrictions in the Act of Union has ceased to be exercised except upon one notable recent occasion.[41]

During the last fifty years some one hundred and fifty additions have been made to the membership of the House of Lords. The only limit to the numerical increase of peers would seem to lie in the good sense of the Prime Minister or the patience of the Sovereign. It is of course the latter who confers peerages, though as the former usually brings suitable candidates for ennoblement to the royal notice, he is generally held responsible for the result of his recommendations.[42]

THE HOUSE OF LORDS IN 1742

THE HOUSE OF LORDS IN 1742The House of Lords now includes some 616 members, divided, as we have seen, into four classes; the Lords Spiritual, the Lords Temporal—Princes of the Blood, Dukes, Marquesses, Earls, Viscounts, Barons—the Representative Peers of Scotland and Ireland, and the Lords of Appeal in Ordinary.

The writ of summons, which did not cease to be regarded as a burden until the reign of Edward II., is now looked upon as a privilege and right which few peers would willingly forego. And the question of mutual precedence which was never mooted until the creation of Viscounts in Henry VI.'s time, is now a matter of the utmost importance to the occupants of the Gilded Chamber.

The first Parliament that is recognized as conferring the right of peerage was that of the eleventh year of Edward I. The Lords decided, in the recent case of Lord Stourton claiming the Barony of Mowbray, that a writ summoning a peer to this Parliament, followed by a sitting, gave his descendants a seat in the House.

All Peers of the Realm—a phrase which came into use in 1322—are entitled to seats in the House of Lords once they have attained their majority. Infancy disqualifies a peer from receiving a writ of summons; failure to take the oath or to affirm deprives him of the right of sitting. No alien may sit in the Lords, nor may a bankrupt or a felon, and the House as a Court of Justice may at any time pass sentence disqualifying a peer from sitting.

The functions of the Upper House which have been the subject of so much recent controversy and are still engrossing the attention of Parliament and the public, have been in former times variously defined by friendly or adverse critics. The[28] Lords have been described as the brake on the parliamentary wheel or as the clog in the parliamentary machine. Horace Walpole wrote some bitter verses on the subject of that House whose members "sleep in monumental state, to show the spot where their great Fathers sate;"

Peers themselves no doubt regard the Upper Chamber as a haven where merit may receive its ultimate reward; where the achievements and the recompense of the deserving are suitably immortalized. As a "compact bulwark against the temporary violence of popular passion," to use Disraeli's phrase, and as a council for weighing the resolutions of the Commons who may at times be led away by public clamour or a sudden impulse, the Second Chamber is regarded by its defenders as of the greatest constitutional value. Lord Salisbury once declared that the chief duty of the House of Lords was to represent the permanent as opposed to the passing feelings of the English nation; "to interpose a salutary obstacle to rash or inconsiderate legislation; and to protect the people from the consequences of their own imprudence." Moreover, the Upper House thus has an opportunity of improving the details of measures, many of which leave the House of Commons in an unworkable shape, owing to the conditions under which they are amended and passed through it, and, but for the alterations effected by the Lords, would remain unworkable when they came to be embodied in the Statute-book.

It has never been the course of the Upper House to resist a continued and deliberately expressed public opinion. The Lords, as Lord Derby affirmed in 1846, "always have bowed and always will bow, to the expression of such opinion."[29][44] But although history to a certain extent bears out this statement, on more than one occasion the hand of popular clamour has battered at their doors for a long time before wringing from them a reluctant acquiescence. There can be no doubt that if the country were to express itself definitely upon any question at a General Election, no House of Lords would be strong enough (or weak enough) to attempt to thwart the public will. But there have been numerous instances in which the peers have endeavoured without success to do so. In vain did they delay Parliamentary Reform in 1831, when Sidney Smith likened the House of Lords to Mrs. Partington, the old lady of Sidmouth who, during the great storm of 1824, tried to push away the Atlantic with her mop.[45] In vain did they inveigh against the passing of the Jewish Oaths Bill or the Bill for the abolition of the Corn Laws. They were eventually compelled to pass the latter, not because they thought it a good Bill, but because, as the Duke of Wellington said, it had passed the House of Commons by a huge majority, and "the Queen's Government must be supported."

On the other side it may be said that they have occasionally interpreted more successfully than the Lower House the views of the electorate, and of this perhaps the rejection of the Home Rule Bill of 1893 is the most prominent example.

Even without actually rejecting Bills the Lords have frequently opposed the will of the Commons by returning the Bills sent up to them in so amended and altered a shape as to prove wholly unacceptable; and an appeal to the country upon every point of difference, or even upon every Bill wholly rejected, is of course impracticable.

In some such cases the Commons have had recourse to a method of coercing the Lords, known by the name of "tacking," which depends for its efficacy upon the acceptation of certain doctrines relating to Money Bills laid down by the[30] Commons at intervals during the last three centuries, and in the main acquiesced in by the Lords.

The history of the matter, though of acute interest at the present time, is too long to go into here. It will be sufficient to mention that in 1678, as the result of a violent struggle between the two Houses, the Commons passed Resolutions asserting (not for the first time) that all Money Bills must have their origin in the Lower House, and that the Hereditary Chamber is powerless to amend them. And though the Lords at the time protested against both these conclusions, by their action through a long course of years they must be taken to have acquiesced in them. If, then, the Lords were unable to amend a Money Bill, they might be compelled to accept an obnoxious measure of a different nature if it were included in such a Bill, the whole of which they would be loth to throw out. This was the process adopted in several instances by the Commons, against which the Lords passed, in 1702, a Standing Order declaring the "annexing any foreign matter" to be "unparliamentary and tending to the destruction of the Constitution."

In 1770 the Commons brought in a Bill to annul the royal grants of forfeited property, and, knowing that it would be objectionable to the Upper House, cunningly tacked it on to a Money Bill. The Lords returned it, with the foreign matter excised; but it was sent back to them once more, and, acting on the advice of the Duke of Marlborough who counselled concession, they eventually swallowed the whole mixture as gracefully as they could find it in their hearts to do. In 1860, the two Houses came into collision again on the same subject, when the Lords threw out the Bill abolishing the duty on paper, which was a financial question. Gladstone retorted in the following year by tacking this Bill on to the Budget, and in this shape the Lords passed it. But their right of rejection—which indeed is involved in the necessity for their assent to every Bill—was never questioned, either in 1678 or since, until the Budget Bill was thrown out in December, 1909, when the[31] whole question of the relations between the two Houses was brought into vital prominence and made the subject of an agitation not easily to be assuaged.

There has always existed a spirit of antagonism between the two Houses. Gladstone declared that the Commons were eyed by the Lords "as Lancelot was eyed by Modred," and this mutual antipathy has occasionally expressed itself in overt acts of rudeness. During a debate in the Lords in 1770, on the defenceless state of the nation, a peer moved that the House be cleared of strangers. A number of the Commons happened to be standing at the Bar, but, notwithstanding their protests, they were unceremoniously hustled out, being followed by a volley of hisses and jeers as they left the Chamber. The Duke of Richmond and many other peers were so disgusted at this exhibition of ill-feeling that they walked out of the House. Colonel Barré has left a graphic description of the scene. The Lords, he says, developed all the passions and violence of a mob. "One of the heads of this mob—for there were two—was a Scotchman. I heard him call out several times, 'Clear the Hoose! Clear the Hoose!' The face of the other was scarcely human; for he had contrived to put on a nose of enormous size, that disfigured him completely, and his eyes started out of his head in so frightful a way that he seemed to be undergoing the operation of being strangled."[46]

Two years after this scene, in 1772, Burke was kept waiting for three hours with a Bill which he was carrying from the Commons to the Lords. When he subsequently reported his ill-treatment to the Lower House, their indignation knew no bounds, and they proceeded to revenge themselves in a somewhat puerile manner. The very next Bill that the House of Lords sent down to them was rejected unanimously, and the Speaker threw the offensive measure on to the floor[32] of the House, whence it was kicked to the door by a number of indignant members.

It is not difficult to understand the cause of jealousy and anger between the Houses, in spite of the fact that so many of the Lords have at one time or another been members of the Commons, and so many of the Commons hope to end their days in the Lords. (Croker, in a letter to Lord Hatherton, recalls a visit he paid as a stranger to the Upper House in 1857, where, of the thirty peers present, there was not one but had sat with him in the Commons, including the Duke of Wellington and the Lord Chancellor. "It shows," he says, "how completely the House of Commons has been the nursery of the House of Lords."[47]) The resentment against the Lords that undoubtedly exists in the bosoms of the Commons, which is not confined to one side of the House, but seems to be universal, results from the power of rejection which the peers can at any time exercise with regard to a measure, or of making amendments by which they can alter it out of all recognition, thus nullifying in a single day the labours of months in the Lower House. And when it is considered that this ruinous result is due not only to men who owe their seats to their successful exertions in various professions, but also in larger proportion to those who owe them to being, as Lord Thurlow said of the Duke of Grafton, "the accident of an accident,"[48] the situation must to many minds appear wholly intolerable.

One very clear cause of failure in the House of Lords to give satisfaction lies in the fact that, although government by Party is the very groundwork of the parliamentary constitution, as far as the Upper House is concerned such an idea might just as well not exist at all. Whatever the political complexion of the party in power in the House of[33] Commons, the Lords maintain an invariable Conservative majority, indifferent to the swing of any popular pendulum, and as fixed and unalterable as the sun. But at no time for the last century has the inequality been so marked as at present, when it may be truthfully said that the Liberal peers would scarcely fill a dozen "hackney coaches."[49] And though the Liberal party has created a considerable number of peers during the last few years, it has never recovered from the secession of Liberal Unionists, and it would take many years of Liberal supremacy and large drafts upon the Prerogative of the Crown to restore even the comparative balance of early Victorian days.

This may or may not be an advantage, for though the staunch Tory is tempted to exclaim in the words of Disraeli: "Thank God there is a House of Lords!" the equally staunch Radical is scarcely likely to consider the existence of this perpetually antagonistic majority a sufficient cause for gratitude towards the Almighty. The difficulty of equalising the parties seems insurmountable, so long as ennoblement is an expensive luxury and Peers continue to be drawn from the wealthy classes.[50] There is, too, something essentially Conservative about the atmosphere of the House of Lords, which sooner or later impregnates the blood of its inmates; under its influence the Liberal of one generation rapidly exhibits a[34] tendency to develop into the Conservative of the next. But this charge is no doubt one which may be brought with more or less truth against any Second Chamber, however constituted, which is composed of men of a certain age and position, not immediately responsible to the fluctuating voices of the people. Whether one considers such stability to be a merit or the reverse depends upon whether one adopts Lord Palmerston's and Lord Salisbury's views of the functions of a Senate, or regards it merely as a useful and select body of legislators enjoying certain limited powers of criticism and delay.

So much has been written about this great modern controversy, that it is unnecessary to increase the literature which exists upon both sides. The issue seems to lie between reducing the Second Chamber to comparative impotence or attempting by judicious reforms in its composition to bring it into greater sympathy with the First Chamber.

The Resolutions recently passed by the Commons,[51] have[35] for their object the complete annihilation of the latter in all matters of finance, and the retention for them of such modified powers of influencing other legislation as would enable them to delay Bills during the early years of a shortened Parliament, and refer them to the country during its last two years. The question of "tacking," in Money Bills, is to be referred to the sole arbitrament of the Speaker; but this becomes of trifling importance when it is argued that almost any revolutionary change could be effected within the corners of a legitimate financial measure. The objection taken to the overriding of the Veto in the case of a Bill thrice presented, is that it amounts to one-Chamber legislation and would result in two classes of Acts—one passed by the Commons alone, and the other by both Houses.

The policy of Reform, on the other hand, is unacceptable to those who desire the predominance of the First Chamber, as any successful scheme for removing present defects in the constitution of the Lords—e.g. the excessive size of the House, the preponderance therein of one party, and the presence of undesirable members—must result in its increased strength and importance. Consequently the Commons have neither made nor encouraged any attempts in that direction.

Such suggestions as have taken any shape have been proposed by the Lords themselves, and the history of the last thirty years exhibits many internal efforts to reform on the part of those dissatisfied with the ancient constitution of the House. In 1884, Lord Rosebery's motion for a Select Committee to consider the best means of promoting the efficiency of the House of Lords, was negatived. Four years later he moved for another Select Committee to inquire into the Constitution of the House. In the same year an[36] elaborate Bill of Lord Dunraven's for reforming the Lords was rejected, and another, promoted by Lord Salisbury, was withdrawn after having passed the second reading. In 1908 a committee met, under the chairmanship of Lord Rosebery, to look into the whole question, and issued a most interesting and practical report, full of admirable recommendations. This committee began by pointing out the expediency of reducing the numbers of an assembly which, within recent years has increased to such an extent as to render itself too unwieldy for legislative purposes. It strongly urged that the recommendations to the Crown for the creation of hereditary peerages should be restricted within somewhat narrower limits. Many peers, as the report explained, are obviously ill-suited to their Parliamentary duties; others find the work irksome and distasteful; of a few it may euphemistically be observed that their release from the burden of legislative responsibilities would be eminently desirable. Lord Rosebery's committee therefore came to the conclusion that the dignity of a peer and the dignity of a Lord of Parliament should be separate and distinct, and that, except in the case of peers of the Blood Royal, the possession of a peerage should not necessarily be attended with the right to sit and vote in the House of Lords. A further suggestion was made that the hereditary peers should be represented by two hundred of their number, elected by them to sit as Lords of Parliament, not for life, but for each parliament, and that the number of Spiritual Peers should be proportionately reduced to ten. The inclusion of representatives from the Colonies, and the granting of a writ of summons to a number of qualified persons who had held high office in the State, figured prominently in this scheme of reform.

Following up these recommendations, the House on the motion of Lord Rosebery has recently adopted the following resolutions for its own reconstitution:—

"(1) That a strong and efficient Second Chamber is not merely an integral part of the British Constitution,[37] but is necessary to the well-being of the State and to the balance of Parliament.

"(2) That such a Chamber can best be obtained by the reform and reconstitution of the House of Lords.

"(3) That a necessary preliminary of such reform and reconstitution is the acceptance of the principle that the possession of a peerage should no longer of itself give the right to sit and vote in the House of Lords."[52]

We are sometimes tempted nowadays to laugh, like "the gardener Adam and his wife," at the claims of long descent. But the pride of birth and blood is common to all nations, perhaps less so in England than elsewhere. The French ducal family of Levis boasted a descent from the princes of Judah, and would produce an old painting in which one of their ancestors was represented as bowing, hat in hand, to the Virgin, who was saying, "Couvrez-vous, mon cousin!" Similarly the family of Cory possessed a picture of Noah with one foot in the ark, exclaiming, "Sauvez les papiers de la maison de Cory!"[53] Byron is said to have been prouder of his pedigree than of his poems, and it is to be hoped that our aristocracy will never entirely forget that their ancestors have handed down to them traditions which are more precious than the titles and lands by which they are represented.

One cannot altogether relish the sight of several peers, who had been considered incompetent to manage their own affairs, hastening to Westminster at the call of a party "Whip" to record their votes upon Imperial concerns of the[38] greatest importance. And though it must be admitted that it is rare indeed for the incompetent or degenerate members of the Upper House to take any part in its deliberations, the fact that they have the undoubted right to do so scarcely tends to enhance the respect in which that assembly is popularly held. In spite, however, of the occasional presence of "undesirables," it is generally acknowledged that if any question arises requiring a display of more than ordinary knowledge of history, or more practical wisdom or learning, these can nowhere be found so well as in the Upper House. There, too, the level of oratory and of common sense is perceptibly higher than in the popular assembly. But the Reform Bill of 1832 enabled the Commons to speak in the name of the people, which they had never hitherto done, and which the Lords cannot do, and thus created that wide gulf which now separates them from the House of Lords. Here, however, as well as there, are many men who realise that, in the words of Lord Rosebery, they have a great heritage, "their own honour, and the honour of their ancestors, and of their posterity, to guard."[54]

The Witenagemot, as we have already seen, was essentially an aristocratic assembly. The populace sometimes attended its meetings, but, beyond expressing their feelings by shouts of approval, took no part in its deliberations. For many years after the Conquest the People continued to be unrepresented in the Great Council of the nation, though they were still present as spectators. From 1066 until about 1225, says Blackstone, the Lords were the only legislators. After the latter date the Commons were occasionally summoned, and in 1265 they formed a regular part of the legislature. Then for the first time did the counties of England return two knights, and the boroughs and cities two deputies each, to represent them in Parliament. Seventy-four knights from all the English counties except Chester, Durham, and Monmouth,[55] and about two hundred burgesses and citizens, sat in the Parliament of Edward I.; but it was not until the reign of his successor that any attempt was made to form a constitutional government.

The Three Estates in those days sat in the same Chamber, but did not join in debate. The Lords made the laws, and the Commons looked on or perhaps assented respectfully. The separation of the two Houses took place in the reign of Edward III., when the knights threw in their allegiance with the burgesses, and in 1322 the Lower House[56] first met apart.

The power of the Commons increased gradually as time advanced. By the end of the thirteenth century they had secured sufficient authority to ensure that no tax could be imposed without their consent. By the middle of the fourteenth no law could be passed unless they approved. But many centuries were yet to elapse before the chief government of the country passed into their hands.

The expense of sending representatives to Parliament was long considered a burden, many counties and boroughs applying to be discharged from the exercise of so costly a privilege. The electors of those days were apparently less anxious to furnish a Member for the popular assembly than to save the payment of his salary. Indeed, the city of Rochester, in 1411, practised the frugal custom of compelling any stranger who settled within its gates to serve a term in Parliament at his own expense. He was thus permitted to earn his freedom, and the parsimonious citizens saved an annual expenditure of about £9.[57]

With the gradual growth of parliamentary power the importance of electing members to the House of Commons began to be recognized, and, during the Wars of the Roses, fewer and fewer applications were made by boroughs and cities anxious to be relieved of this duty.

Until Henry VI.'s time, when the modern system of Bills and Statutes began to come into being, legislation was by Petition. The control of Parliament was still very largely in the hands of the Crown, and successive sovereigns took care that their influence over the Commons should be maintained. With this object in view Edward VI. enfranchised some two-and-twenty rotten boroughs, Mary added fourteen more, and in Elizabeth's time sixty-two further members, all under the royal control, were sent to leaven the Commons.

The attendance in the Lower House was still poor, not[41] more than two hundred members ever taking part in the largest divisions, and it was only at the culmination of the conflicts between Parliament and the Stuart Kings that the Commons began to display a real desire for independent power.