The Project Gutenberg EBook of Nooks and Corners of the New England Coast, by Samuel Adams Drake This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Nooks and Corners of the New England Coast Author: Samuel Adams Drake Release Date: February 21, 2012 [EBook #38941] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NOOKS, CORNERS--NEW ENGLAND COAST *** Produced by Annie R. McGuire. This book was produced from scanned images of public domain material from the Google Print archive.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1875, by

HARPER & BROTHERS,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

Inscribed by Permission,

AND WITH SENTIMENTS OF HIGH RESPECT,

TO

HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW.

Norumbega River and City.—Early Discoverers, and Maps of New England.—Mode of taking Possession of new Countries.—Cruel Usage of Intruders by the English.—Penobscot Bay.—Character of first Emigrants to New England.—Is Friday unlucky?

About Islands.—Champlain's Discovery.—Mount Desert Range.—Somesville, and the Neighborhood.—Colony of Madame De Guercheville.—Descent of Sir S. Argall.—Treasure-trove.—Shell-heaps.—South-west Harbor.—The natural Sea-wall.—Islands off Somes's Sound

Excursion to Bar Harbor.—Green Mountain.—Eagle Lake.—Island Nomenclature.—Porcupine Islands.—Short Jaunts by the Shore.—Schooner Head.—Spouting Caves.—Sea Aquaria.—Audubon and Agassiz.—David Wasgatt Clark.—F. E. Church and the Artists.—Great Head.—Baye Françoise.—Mount Desert Rock.—Value of natural Sea-marks.—Newport Mountain, and the Way to Otter Creek.—The Islesmen.—North-east Harbor.—The Ovens.—The Gregoires.—Henrietta d'Orleans.—Yankee Curiosity

Pentagoët.—A Fog in Penobscot Bay.—Rockland.—The Muscongus Grant.—Colonial Society.—Generals Knox and Lincoln.—Camden Hills.—Belfast and the River Penobscot.—Brigadier's Island.—Disappearance of the Salmon.—Approach to Castine.—Fort George.—Penobscot Expedition.—Sir John Moore.—Capture of General Wadsworth.—His remarkable Escape.—Rochambeau's Proposal.—La Peyrouse

Old Fort Pentagoët.—Stephen Grindle's Windfall.—Cob-money.—The Pilgrims at Penobscot.—Isaac de Razilly.—D'Aulnay Charnisay.—La Tour.—Descent of Sedgwick and Leverett.—Capture of Pentagoët, and Imprisonment of Chambly.—Colbert.—Baron Castin.—The younger Castin kidnaped.—Capuchins and Jesuits.—Intrigues of De Maintenon and Père Lachaise.—Burial-ground of Castine.—About the Lobster.—Where is Down East?

New Harbor.—Wayside Manners.—British Repulse at New Harbor.—Porgee Factory.—Process of converting the Fish into Oil.—Habits of the Mackerel.—Weymouth's Visit to Pemaquid.—Champlain again.—Popham Colony.—Cotton Mather on new Settlements.—English vs. French Endurance.—L'Ordre de Bon Temps.—Samoset.—Fort Frederick.—Résumé of the English Settlement and Forts.—John Nelson.—Capture of Fort William Henry.—D'Iberville, the knowing One.—Colonel Dunbar at Pemaquid.—Shell-heaps of Damariscotta.—Disappearance of the native Oyster in New England

Scenes on a Penobscot Steamer.—The Islanders.—Weymouth's Anchorage.—Monhegan described.—Combat between the Enterprise and Boxer.—Lieutenant Burrows

Wells.—John Wheelwright.—George Burroughs.—On the Beach.—Shiftings of the Sands.—What they produce.—Ingenuity of the Crow.—The Beach as a High-road.—Popular Superstitions.—Ogunquit.—Bald Head Cliff.—Wreck of the Isidore.—Kennebunkport.—Cape Neddock.—The Nubble.—Captains Gosnold and Pring.—Moon-light on the Beach

Mount Agamenticus.—Basque Fishermen.—Sassafras.—The Long Sands.—Sea-weed and Shell-fish.—Foot-prints.—Old York Annals.—Sir Ferdinando Gorges.—York Meeting-house.—Handkerchief Moody.—Parson Moody.—David Sewall.—Old Jail.—Garrison Houses, Scotland Parish

York Bridge.—Poor Sally Cutts.—Fort M'Clary.—Sir William Pepperell.—Louisburg and Fontenoy.—Gerrish's Island.—Francis Champernowne.—Islands belonging to Kittery.—John Langdon.—Jacob Sheaffe.—Washington at Kittery

De Monts sees them.—Smith's and Levett's Account.—Cod-fishery in the sixteenth Century.—Sail down the Piscataqua.—The Isles.—Derivation of the Name.—Jeffrey's Ledge.—Star Island.—Little Meeting-house.—Character of the Islesmen.—Island Grave-yards.—Betty Moody's Hole.—Natural Gorges.—Under the Cliffs.—Death of Miss Underhill.—Story of her Life.—Boon Island.—Wreck of the Nottingham.—Fish and Fishermen.

Excursion to Smutty Nose.—Piracy in New England Waters.—Blackbeard.—Thomas Morton's Banishment.—Religious Liberty vs. License.—Custom of the May-pole.—Samuel Haley.—Spanish Wreck on Smutty Nose.—Graves of the Unknown.—Terrible Tragedy on the Island.—Appledore.—Its ancient Settlement.—Smith's Cairn.—Duck Island.—Londoner's.—Thomas B. Laighton.—Mrs. Thaxter.—Light-houses in 1793.—White Island.—Story of a Wreck.

The Way to the Island.—The Pool.—Ancient Ships.—Old House.—Town Charter and Records.—Influence of the Navy-yard.—Fort Constitution.—Little Harbor.—Captain John Mason.—The Wentworth House.—The Portraits.—The Governors Wentworth and their Wives.—Baron Steuben.

The Witch-ground.—Antiquity of Witchcraft.—First Case in New England.—Curiosities of Witchcraft.—Rebecca Nurse.—Beginning of Terrorism at Salem Village.—Humors of the Apparitions.—General Putnam's Birthplace.—What may be seen in Danvers.

Salem in 1692.—Birthplace of Hawthorne.—Old Witch House.—William Stoughton, Governor.—Witch Hill.—A Leaf from History.

The Rock of Marblehead.—The Harbor and Neck.—Chat with the Light-keeper.—Decline of the Fisheries.—Fishery in the olden Time.—Early Annals of Marblehead.—Walks about the Town.—Crooked Lanes and antique Houses.—The Water-side.—The Fishermen.—How the Town looked in the Past.—Plain-spoken Clergymen and lawless Parishioners.—Anecdotes.—Jeremiah Lee and his Mansion.—The Town-house.—Chief-justice Story.—St. Michael's Church.—Elbridge Gerry.—The old Ironsides of the Sea.—General John Glover.—Flood Ireson's, Oakum Bay.—Fort Sewall.—Escape of the Constitution Frigate.—Duel of the Chesapeake and Shannon.—Old Burial-ground.—The Grave-digger.—Perils of the Fishery.

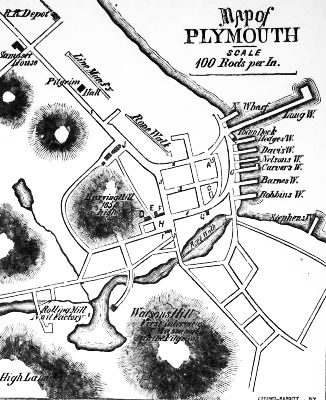

At the American Mecca.—Court Street.—Pilgrim Hall and Pilgrim Memorials.—Sargent's Picture of the "Landing."—Relics of the Mayflower.—First Duel in New England.—Old Colony Seal.—The "Compact."—First Execution in Plymouth.—Old "Body of Laws."—Pilgrim Chronicles.—View from Burial Hill.—The Harbor.—Names of Plymouth.—Plymouth, England.—Lord Nelson's Generosity.—Plymouth the temporary Choice of the Pilgrims.—The Indian Plague.—Indian Superstition.—Who was first at Plymouth?—De Monts and Champlain.—Champlain's Voyages in New England.—French Pilgrims make the first Landing.—Why the Natives were hostile to the Pilgrims of 1620.—Confusion among old Writers about Plymouth.—Among the Tombstones of Burial Hill.—The Pilgrims' Church-fortress.—What a Dutchman saw here in 1627.—Military Procession to Meeting.—Ancient Church Customs.—Puritans, Separatists, and Brownists.—Flight and Political Ostracism of the Pilgrims.—Their form of Worship.—First Church of Salem.—Plymouth founded on a Principle.

Let us walk in Leyden Street.—The way Plymouth was built.—Governor Bradford's Corner.—Fragments of Family History.—How Marriage became a civil Act.—The Common-house.—John Oldham's Punishment.—The Allyne House.—James Otis and his Sister Mercy.—James Warren.—Cole's Hill, and its obliterated Graves.—Plymouth Rock.—True Date of the "Landing."—Christmas in Plymouth, and Bradford's Joke.—Pilgrim Toleration.—Samoset surprises Plymouth.—The Entry of Massasoit.—First American Congress.—To Clark's Island.—Watson's House.—Election Rock.—The Party of Discovery.—Duxbury.—Captains Hill and Miles Standish.—John Alden.—"Why don't you speak for yourself?"—Historical Iconoclasts.—Celebrities of Duxbury.—Winslow and Acadia.—Colonel Church.—The Dartmouth Indians.

Cape Cod a Terra incognita.—Appearance of its Surface.—Historical Fragments.—The Pilgrims' first Landing.—New England Washing-day.—De Poutrincourt's Fight with Natives.—Provincetown described.—Cape Names.—Portuguese Colony.—Cod and Mackerel Fishery.—Cod-fish Aristocracy.—Matt Prior and Lent.—Beginning of Whaling.—Mad Montague.—The Desert.—Cranberry Culture.—The moving Sand-hills.—Disappearance of ancient Forests.—The Beach.—Race Point.—Huts of Refuge.—Ice Blockade of 1874-'75.—Wreck of the Giovanni.—Physical Aspects of the Cape Shores.—Old Wreck at Orleans.

The old Voyagers again.—Derivation of the Name of Nantucket.—Sail from Wood's Hole to the Island.—Vineyard Sound.—Walks in Nantucket Streets.—Whales, Ships, and Whaling.—Nantucket in the Revolution.—Cruising for Whales.—The Camels.—Nantucket Sailors.—Loss of Ship Essex.—Town-crier.—Island History.—Quaker Sailors.—Thomas Mayhew.—Spermaceti.—Macy, Folger, Admiral Sir Isaac Coffin.

Taking Blackfish.—Blue-fishing at the Opening.—Walk to Coatue.—The Scallop-shell.—Structure of the Island.—Indian Legends.—Shepherd Life.—Absolutism of Indian Sagamores.—Wasting of the Shores of the Island.—Siasconset.—Nantucket Carts.—Fishing-stages.—The Great South Shoal.—Sankoty Light.—Surfside.

General View of Newport.—Sail up the Harbor.—Commercial Decadence.—Street Rambles.—William Coddington.—Anne Hutchinson.—The Wantons.—Newport Artillery.—State-house Notes.—Tristram Burgess.—Jewish Cemetery and Synagogue.—Judah Touro.—Redwood Library.—The Old Stone Mill.

The Cliff Walk.—Newport Cottages and Cottage Life.—Charlotte Cushman.—Fort Day and Fort Adams.—Bernard, the Engineer.—Dumplings Fort.—Canonicut.—Hessians.—Newport Drives.—The Beaches.—Purgatory.—Dean Berkeley.

Behavior of the Troops.—Monarchy aiding Democracy.—D'Estaing.—Jourdan.—French Camps.—Rochambeau, De Ternay, De Noailles.—Efforts of England to break the Alliance.—Frederick's Remark.—Malmesbury and Potemkin.—Lord North and Yorktown.—George III.—Biron, Duc de Lauzun.—Chastellux, De Castries, Vioménil, Lameth, Dumas, La Peyrouse, Berthier, and Deux-Ponts.—The Regiment Auvergne.—Latour D'Auvergne.—French Diplomacy.

Rhode Island Cemetery.—Curious Inscriptions.—William Ellery.—Oliver Hazard Perry.—The Quakers.—George Fox.—Quaker Persecution.—Other Grave-yards.—Lee and the Rhode Island Tories.—Coddington and Gorton.—John Coggeshall.—Trinity Church-yard.—Dr. Samuel Hopkins.—Gilbert Stuart.

Walk up the Island.—"Tonomy" Hill.—The Malbones.—Capture of General Prescott.—Talbot's Exploit.—Ancient Stages.—Windmills.—About Fish.—Lawton's Valley.—Battle of 1778.—Island History.—Mount Hope.—Philip's Death.—Dighton Rock.—Indian Antiquities.

Entrance to the Thames.—Fisher's Island.—Block Island.—New London.—Light-ships and Light-houses.—Hempstead House.—Bishop Seabury.—Old Burial-ground.—New London Harbor.—The little Ship-destroyer.—Groton and Monument.—Arnold.—British Attack on Groton.—Fort Griswold.—The Pequots.—John Mason.—Silas Deane.—Beaumarchais.—John Ledyard.—Decatur and Hardy.—Norwich City.—The Yantic picturesque.—Uncas, the Mohegan Chieftain.—Norwich Town.—Fine old Trees.—The Huntingtons.

Old Saybrook.—Disappearance of the Yankee.—Old Girls.—Isaac Hull.—The Harts.—Connecticut River.—Old Fortress.—Dutch Courage.—The Pilgrims' Experiences.—Cromwell, Hampden, and Pym.—Lady Fenwick.—George Fenwick.—Lion Gardiner.—Old Burial-ground.—Yale College.—The Shore, and the End.

"This is the forest primeval. The murmuring pines and the hemlocks,

Bearded with moss, and with garments green, indistinct in the twilight,

Stand like Druids of Old, with voices sad and prophetic,

Stand like harpers hoar, with beards that rest on their bosoms.

Loud from its rocky caverns the deep-voiced neighboring ocean

Speaks, and in accents disconsolate answers the wail of the forest."

Longfellow.

In many respects the sea-coast of Maine is the most remarkable of New

England. It is serrated with craggy projections, studded with harbors,

seamed with inlets. Broad bays conduct to rivers of great volume that

annually bear her forests down to the sea. Her shores are barricaded

with islands, and her waters teem with the abundance of the seas. Seen

on the map, it is a splintered, jagged, forbidding sea-board; beheld

with the eye in a kindly season, its tawny headlands, green

archipelagos, and inviting harbors,[Pg 17]

[Pg 18] infolding sites recalling the

earlier efforts at European colonization, combine in a wondrous degree

to win the admiration of the man of science, of letters, or of leisure.

Maine embraces within her limits the semi-fabulous Norumbega and Mavoshen of ancient writers. Some portion of her territory has been known at various times by the names of Acadia, New France, and New England. The arms of France and of England have alternately been erected on her soil, and the flags of at least four powerful states have claimed her subjection. The most numerous and warlike of the primitive New England nations were seated here. Traces of French occupation are remaining in the names of St. Croix, Mount Desert, Isle au Haut, and Castine, names which neither treaties nor national prejudice have been quite able to eradicate.

The name of Norumbega, or Norembegue, the earliest applied to New England, is attributed to the Portuguese and Spaniards. Jean Alfonse, the pilot of Roberval, the same person who is accredited with having been first to navigate the waters of Massachusetts Bay, gives them the credit of its discovery. It is true that Marc Lescarbot, the Parisian advocate whose relations are the foundations of so many others, was at the colony of Port Royal in the year 1606, with Pontgravé Champlain, and De Poutrincourt. This writer discredits all of Alfonse's statement in relation to the great river and coast of Norumbega, except that part of it in which he says the river had at its entrance many islands, banks, and rocks. In this fragment from the "Voyages Aventureux" of Alfonse, the embouchure of the river of Norumbega is placed in thirty degrees ("trente degrez") and the pilot states that from thence the coast turns to the west and west-north-west for more than two hundred and fifty leagues.[1] The most casual reader will know how to value such a relation without reference to the sarcasm of Lescarbot, when he says, "And well may he call his voyages adventurous, not for himself, who was never in the hundredth part of the places which he describes (at least it is easy to conjecture so), but for those who might wish to follow the routes which he directs the mariner to follow." After this, his claim to be considered the first European navigator in Massachusetts Bay must be received with many grains of allowance.

Champlain, who remained in the country through the winter of 1605, on purpose to complete his map, has this to say of the river and city of Norumbega; he is writing of the Penobscot:

"I believe this river is that which several historians call Norumbegue, and which the greater part have written, is large and spacious, with many islands; and its entrance in forty-three and forty-three and a half; and others in forty-four, more or less, of latitude. As for the declination, I have neither[Pg 19] read nor heard any one speak of it. They describe also a great and very populous city of natives, dexterous and skillful, having cotton cloth. I am satisfied that the major part of those who make mention of it have never seen it, and speak from the hearsay evidence of those who know no more than themselves. I can well believe that there are some who have seen the embouchure, for the reason that there are, in fact, many islands there, and that it lies in the latitude of forty-four degrees at its entrance, as they say; but that any have entered it is not credible; for they must have described it in quite another manner to have removed this doubt from many people." With this protest Champlain admits the country of Norumbega to a place on his map of 1612.

In the "Histoire Universelle des Indes Occidentales" printed at Douay in 1607, the author, after describing Virginia, speaks of Norumbega, its great river and beautiful city. The mouth of the river is fixed in the forty-fourth and the pretended city in the forty-fifth degree, which approximates closely enough to the actual latitude of the Penobscot. This authority adds, that it is not known whence the name originated, for the Indians called it Agguncia.[2] It also refers to the island well situated for fishery at the mouth of the great river. On the map of Ortelius (1603) the two countries of Norumbega and Nova Francia occupy what is now Nova Scotia and New England respectively. The only features laid down in Nova Francia by name are "R. Grande Orsinora," "C. de Iaguas islas," and "Montagnes St. Jean." These localities answer reasonably well to as many conjectures as there are mountains, streams, and capes in New England; there is no projection of the coast corresponding with Cape Cod. Champlain names the River Penobscot, Pemetegoit. By this appellation, with some trivial change in orthography, it continued known to the French until its final repossession by the English.[3]

Turning to the "painful collections of Master Hakluyt," the old prebendary of Bristol, we find Mavoshen described as "a country lying to the north and by east of Virginia, between the degrees of 43 and 45, fortie leagues broad and fifty in length, lying in breadth east and west, and in length north and south. It is bordered on the east with a countrey, the people whereof they call Tarrantines, on the west with Epistoman, on the north with a very great wood, called Senaglecounc, and on the south with the mayne ocean sea and many islands." In all these relations there is something of fact, but much more that is too unsubstantial for the historian's acceptance. The voyages of the Norsemen, of De Rut, and Thevet are still a[Pg 20] disputed and a barren field. I do not propose here to indulge in speculations respecting them.

Francis I. demanded, it is said, to be shown that clause in the will of Adam which disinherited him in the New World for the benefit of the Spaniards. Under his favor, the Florentine Verrazani put to sea from Dieppe, in Le Dauphine, in the year 1524.[4] By virtue of his discoveries the French nation claimed all the territory now included in New England. The astute Francis followed up the clew by dispatching, in 1534, Jacques Cartier in La Grande Hermine. Despite the busy times in Europe, near the close of his reign, Henry IV. continued to favor projects confirming the footing obtained by his predecessors. Until 1614, when the name of New England first appeared on Smith's map, the French had the honor of adding about all that was known to the geography of its sea-board.

There can now be no harm in saying that Captain John Smith was not the first to give a Christian name to New England. The Florentine Verrazani called it, in 1524, New France, when he traversed the coasts from the thirty-fourth parallel to Newfoundland, or Prima Vista. Sebastian Cabot may have seen it before him; but this is only conjecture, though our great-grandfathers were willing to spill their blood rather than have it called New France. According to the "Modern Universal History," Cabot confessedly took formal possession of Newfoundland and Norumbega, whence he carried off three natives. In the "Theatre Universel d'Ortelius" there is a map of America, engraved in 1572, and very minute, in which all the countries north[Pg 21] and south are entitled New France. "The English," says a French authority, "had as yet nothing in that country, and there is nothing set down on this map for them."

In Mercator's atlas of 1623 is a general map of America, which calls all the territory north and south of Canada New France. New England does not find a place on this map. Canada is down as a particular province. Virginia is also there.

Captain John Smith's map of New England of 1614 contains many singular features. In his "Description of New England," printed in 1616, the Indian names are given of all their coast settlements. Prince Charles, however, altered these to English names after the book was printed. The retention of some of them by the actual settlers might be accidental, but they appear much as if scattered at random over the paper. "Plimouth" is where it was located six years after the date of the map. York is called Boston, and Agamenticus "Snadoun Hill." Penobscot is called "Pembrock's Bay."

The name of Cape Breton is said to occur on very early maps, antecedent even to Cartier's voyage. A map of Henry II. is the oldest mentioned. "Nurembega" is on a map in "Le Receuil de Ramusius"[5] tome iii., where there is an account of a Frenchman of Dieppe, and a map made before the discovery of "Jean Guartier." It is asserted that the Basque and Breton fishermen were on the coast of America before the Portuguese and Spaniards. Baron La Hontan says, "The seamen of French Biscay are known to be the most able and dexterous mariners that are in the world." It is pretty certain that Cape Breton had this name before the voyages of Cartier or Champlain. The Frenchman of Dieppe is supposed to be Thomas Aubert, whose discovery is assigned to the year 1508.

The atlas of Guillaume and John Blauw has a map of America in tome i. There is a second, entitled Nova Belgica and Nova Anglica. New England extends no farther than the Kennebec, where begins the territory of Nova Franciæ Pars, in which Norumbega is located. The rivers Pentagouet and Chouacouet (Saco) appear properly placed. The map bears certain marks in[Pg 22] its nomenclature, and the configuration of the coast, of being compiled from those of Champlain and Smith.[6]

Researches made in England, France, and Holland, at the instance of Massachusetts and New York,[7] have resulted in the recovery of many manuscript fragments more or less interesting, bearing upon the question of priority of discovery. Of these the following is not the least curious. If credence may be placed in the author of the "Memoires pour servir à l'Histoire de Dieppe," "Recherches sur les Voyages et decouvertes des Navigateurs Normands," and "Navigateurs Français," the continent of America was discovered by Captain Cousin in the year 1488. Sailing from Dieppe, he was carried westward by a gale, and drawn by currents to an unknown coast, where he saw the mouth of a large river.

Cousin's first officer was "un étranger nommé Pinçon ou Pinzon," who instigated the men to mutiny, and was so turbulent that, on the return of the caravel, Cousin charged him before the magistrates of Dieppe with mutiny, insubordination, and violence. He was banished from the city, and embarked four years afterward, say the Dieppois, with Christopher Columbus, to whom he had given information of the New World.[8]

In the "Bibliothéque Royale" of Paris there is, or rather was, existing a manuscript (dated in 1545) entitled "Cosmographie de Jean Alfonce le Xaintongeois." It is undoubtedly from this manuscript that Jean de Marnef and De St. Gelais compiled the "Voyages Aventureux d'Alfonce Xaintongeois," printed in 1559, which includes an expedition along the coast from Newfoundland southwardly to "une baye jusques par les 42 degrés, entre la Norembegue et la Fleuride," in 1543.

Of Jean Alfonse it is known that he was one of Roberval's pilots, in his voyage of 1542 to Canada, and that he returned home with Cartier. Roberval expected to find a north-west passage, and Jean Alfonse, who searched the coast for it, believed the land he saw to the southward to be part of the continent of Asia. His cruise within the latitude of Massachusetts Bay is also mentioned by Hakluyt. The claim of Alfonse to be the discoverer of Massachusetts Bay has been set forth with due prominence.[9] Alfonse and Champlain were both from the same old province in the west of France.

It goes without dispute that the older French historians knew little or[Pg 23] nothing of Hakluyt and Purchas. So little did the affairs of the New World engage their attention, that in the "History of France," by Father Daniel, printed at Amsterdam in 1720, by the Company of Jesuits, in six ponderous tomes, the discoveries and settlements in New France (Canada) occupy no more than a dozen lines. Cartier, Roberval, De Monts, and Champlain are mentioned, and that is all.

When a vessel of the old navigators was approaching the coast, the precaution was taken of sending sailors to the mast-head. These lookouts were relieved every two hours until night-fall, at which time, if the land was not yet in sight, they furled their sails so as to make little or no way during the night. It was a matter of emulation among the ship's company who should first discover the land, as the passengers usually presented the lucky one with some pistoles. One writer mentions that on board French vessels, after sighting Cape Race, the ceremony known among us as "crossing the line" was performed by the old salts on the green hands, without regard to season.

The method of taking possession of a new country is thus described in the old chronicles: Jacques Cartier erected a cross thirty feet high, on which was suspended a shield with the arms of France and the words "Vive le Roy." Sir Humphrey Gilbert, in 1583, raised a pillar at Newfoundland, with a plate of lead, having the queen's arms "graven thereon." A turf and a twig were presented to him, which he received with a hazel wand. The expression "by turf and twig," a symbol of actual possession of the soil and its products, is still to be met with in older New England records.

Douglass, the American historian, speaking of Henry IV., says, "He planted[Pg 24] a colony in Canada which subsists to this day. May it not long subsist; it is a nuisance to our North American settlements: Delenda est Carthago."

The insignificant attempt of Gosnold, in 1603, and the disastrous one of Popham, in 1607, contributed little to the knowledge of New England. But the absence of any actual possession of the soil did not prevent the exercise of unworthy violence toward intruders on the territory claimed by the English crown. In 1613 Sir Samuel Argall broke up the French settlement begun at Mount Desert in that year, opening fire on the unsuspecting colonists before he gave himself the trouble of a formal summons. Those of other nations fared little better, as the following recital will show:

Purchas relates that "Sir Bernard Drake, a Devonshire knight, came to Newfoundland with a commission; and having divers good ships under his command, he took many Portugal ships, and brought them into England as prizes.

"Sir Bernard, as was said, having taken a Portugal ship, and brought her into one of our western ports, the seamen that were therein were sent to the prison adjoining the Castle of Exeter. At the next assizes held at the castle there, about the 27th of Queen Elizabeth, when the prisoners of the county were brought to be arraigned before Sergeant Flowerby, one of the judges appointed for this western circuit at that time, suddenly there arose such a noisome smell from the bar that a great number of people there present were therewith infected; whereof in a very short time after died the said judge, Sir John Chichester, Sir Arthur Bassett, and Sir Bernard Drake, knights, and justices of the peace there sitting on the bench; and eleven of the jury impaneled, the twelfth only escaping; with divers other persons."

Captain John Smith says: "The most northern part I was at was the Bay of Penobscot, which is east and west, north and south, more than ten leagues; but such were my occasions I was constrained to be satisfied of them I found in the bay, that the river ran far up into the land, and was well inhabited with many people; but they were from their habitations, either fishing among the isles, or hunting the lakes and woods for deer and beavers.

"The bay is full of great islands of one, two, six, eight, or ten miles in length, which divide it into many faire and excellent good harbours. On the east of it are the Tarrantines, their mortal enemies, where inhabit the[Pg 25] French, as they report, that live with these people as one nation or family."

If the English had no special reason for self-gratulation in the quality of the emigrants first introduced into New England, the French have as little ground to value themselves. In order to people Acadia, De Monts begged permission of Henri Quatre to take the vagabonds that might be collected in the cities, or wandering at large through the country. The king acceded to the request.[10]

Again, in a memoir on the state of the French plantations, the following passage occurs: "The post of Pentagouet, being at the head of all Acadia on the side of Boston, appears to have been principally strengthened by the sending over of men and courtesans that his majesty would have emigrate there for the purpose of marrying, so that this portion of the colony may receive the accessions necessary to sustain it against its neighbors."[11]

These statements are supported by the testimony of the Baron La Hontan, who relates that, after the reorganization of the troops in Canada, "several ships were sent hither from France with a cargo of women of ordinary reputation, under the direction of some old stale nuns, who ranged them in[Pg 26] three classes. The vestal virgins were heaped up (if I may so speak), one above another, in three different apartments, where the bridegrooms singled out their brides just as a butcher does ewes from among a flock of sheep. The sparks that wanted to be married made their addresses to the above-mentioned governesses, to whom they were obliged to give an account of their goods and estates before they were allowed to make their choice in the seraglio." After the selection was made, the marriage was concluded on the spot, in presence of a priest and a notary, the governor-general usually presenting the happy couple with some domestic animals with which to begin life anew.

When the number of historical precedents is taken into account, the superstition long current among mariners with regard to setting sail on Friday seems unaccountable. Columbus sailed from Spain on Friday, discovered land on Friday, and returned to Palos on Friday. Cabot discovered the American continent on Friday. Gosnold sailed from England on Friday, made land on Friday, and came to anchor on Friday at Exmouth. These coincidences might, it would seem, dispel, with American mariners at least, something of the dread with which a voyage begun on that day has long been regarded.

"There, gloomily against the sky,

The Dark Isles rear their summits high;

And Desert Rock, abrupt and bare,

Lifts its gray turrets in the air."

Whittier.

Islands possess, of themselves, a magnetism not vouchsafed to any spot of the main-land. In cutting loose from the continent a feeling of freedom is at once experienced that comes spontaneously, and abides no longer than you remain an islander. You are conscious, in again setting foot on the main shore, of a change, which no analysis, however subtle, will settle altogether to your liking. Upon islands the majesty and power of the ocean come home to you, as in multiplying itself it pervades every fibre of your consciousness, gaining in vastness as you grow in knowledge of it. On islands it is always present—always roaring at your feet, or moaning at your back.

Islands have had no little share in the world's doings. Corsica, Elba, and St. Helena are linked together by an unbroken historical chain. Homer and the isles of Greece, Capri and Tiberius loom in the twilight of antiquity. Thinking on Garibaldi or Victor Hugo, the mind instinctively lodges on Caprera or Guernsey. An island was the death of Philip II., and the ruin of Napoleon. In the New World, Santo Domingo, Cuba, and Newfoundland were first visited by Europeans.

The islands of the New England coast have become beacons of her history. Mount Desert, Monhegan, and the Isles of Shoals, Clark's Island, Nantucket, The Vineyard, and Rhode Island have havens where the historian or antiquary must put in before landing on broader ground. I might name a score of[Pg 28] others of lesser note; these are planets in our watery system. On this line many peaceful summer campaigns have been brought to a happy conclusion. Not a few have described the more genial aspects of Mount Desert. It has in fact given employment to many busy pens and famous pencils. I am not aware that its wintry guise has been portrayed on paper or on canvas. The very name is instinctively associated with an idea of desolateness:

"The gray and thunder-smitten pile

Which marks afar the Desert Isle."

Champlain was no doubt impressed by the sight of its craggy summits, stripped of trees, basking their scarred and splintered steeps in a September sun. "I have called it," he says, "the Isle of Monts Déserts."

In a little "pattache" of only seventeen or eighteen tons burden, he had set out on the 2d of September, 1604, from St. Croix, to explore the coast of Norumbega. Two natives accompanied him as guides. The same day, as they passed close to an island four or five leagues long, their bark struck a hardly submerged rock, which tore a hole near the[Pg 29] keel. They either sailed around the island, or explored it by land, as the strait between it and the main-land is described as being not more than a hundred paces in breadth. "The land," continues the French voyager, "is very high, intersected by passes, appearing from the sea like seven or eight mountains ranged near each other. The summits of the greater part of these are bare of trees, because they are nothing but rocks." It was during this voyage, and with equal pertinence, Champlain named Isle au Haut.[12] According to Père Biard, the savages called the island of Mount Desert "Pemetiq" "meaning," says M. l'Abbé Maurault, "that which is at the head." A crowned head it appears, seen on land or sea.

It is curious to observe how the embouchure of the Penobscot is on either shore guarded by two such solitary ranges of mountains as the Camden and Mount Desert groups. They embrace about the same number of individual peaks, and approximate nearly enough in altitude. From Camden we may skirt the shores for a hundred and fifty miles to the west and south before meeting with another eminence; and then it is an isolated hill standing almost upon the line of division between Maine and New Hampshire that is encountered. On the shore of the main-land, west of Mount Desert, is Blue Hill, another lone mountain. Katahdin is still another astray, of grander proportions, it is true, but belonging to this family of lost mountains. Although they appear a continuous chain when massed by distance, the Mount[Pg 30] Desert range is, in reality, broken into little family groups, as exhibited on the map.

Another peculiarity of the Mount Desert chain is that the eastern summits are the highest, terminating generally in precipitous and inaccessible cliffs. I asked a village ancient his idea of the origin of these mountains, and received it in two words, "Hove up." The cluster numbers thirteen eminences, to which the title "Old Thirteen" may be more fitly applied than to any political community of modern history. This assemblage of hills with lakes in their laps at once recalled the Adirondack region, with some needful deductions for the height and nakedness of the former when compared with the greater altitudes and grand old forests of the wilderness of northern New York.

Should any adventurous spirit, after reading these pages, wish to see the Desert Isle in all its rugged grandeur, he may do so at the cost of some trifling inconveniences that do not fall to the lot of the summer tourist. In this case, Bangor or Bucksport will be the point of departure for a journey of from thirty to forty miles by stage. I came to the island by steamboat from Boston, which landed me at Bucksport; whence I made my way via Ellsworth to Somesville.

After glancing at the map of the island, I chose Somesville as a central point for my excursions, because it lies at the head of the sound, that divides the island almost in two, is the point toward which all roads converge, and is about equally distant from the harbors or places of particular resort. In summer I should have adopted the same plan until I had fully explored the shores of the Sound, the mountains that are contiguous, and the western half of the island. In twenty-four hours the visitor may know by heart the names of the mountains, lakes, coves, and settlements, with the roads leading to them; he may thereafter establish himself as convenience or fancy shall dictate. At Somesville there is a comfortable hostel, but the larger summer hotels are at Bar Harbor and at South-west Harbor.

The accentuation should not fall on the last, but on the first syllable of Desert, although the name is almost universally mispronounced in Maine, and notably so on the island itself. Usually it is Mount Desart, toned into Desert by the casual population, who thus give it a curious significance.

Mount Desert is one of the wardens of Penobscot Bay, interposing its bulk between the waters of Frenchman's Bay on the east and Blue Hill Bay on the west. A bridge unites it with the main-land in the town of Trenton, where the opposite shores approach within rifle-shot of each other. This point is locally known as the Narrows. When I crossed, the tide was pressing against the wooden piers, in a way to quicken the pace, masses of newly-formed ice that had floated out of Frenchman's Bay with the morning's ebb.

You get a glimpse of Mount Desert in sailing up Penobscot Bay, where its mountains appear foreshortened into two cloudy shapes that you would fail to know again. But the highest hills between Bucksport and Ellsworth[Pg 31] display the whole range; and from the latter place until the island is reached their snow-laced sides loomed grandly in the gray mists of a December day. In this condition of the atmosphere their outlines seemed more sharply cut than when thrown against a background of clear blue sky. I counted eight peaks, and then, on coming nearer, others, that at first had blended with those higher and more distant ones, detached themselves. Green Mountain will be remembered as the highest of the chain, Beech and Dog mountains from their peculiarity of outline. A wider break between two hills indicates where the sea has driven the wedge called Somes's Sound into the side of the isle. Western Mountain terminates the range on the right; Newport Mountain, with Bar Harbor at its foot, is at the other extremity of the group. In approaching from sea this order would appear reversed.

The Somesville road is a nearly direct line drawn from the head of the Sound to the Narrows. Soon after passing the bridge, that to Bar Harbor diverged to the left. Crossing a strip of level land, we began the ascent of Town Hill through a dark growth of cedar, fir, and other evergreen trees. A little hamlet, where there is a post-office, crowns the summit of Town Hill. Not long after, the Sound opened into view one of those rare vistas that leave a picture for after remembrance. At first it seemed a lake shut in by the feet of two interlocking mountains, but the vessels that lay fast-moored in the ice were plainly sea-going craft. Somesville lay beneath us, its little steeple pricking the frosty air. Cold, gray, and cheerless as their outward dress appeared, the mountains had more of impressiveness, now that they were covered from base to summit with snow. They seemed really mountains and not hills, receiving an Alpine tone with their wintry vesture.

After all, a winter landscape in New England is less gloomy than in the same zone of the Mississippi Valley, where, in the total absence of evergreen-trees, nothing but long reaches of naked forest rewards the eye, which roves in vain for some vantage-ground of relief. Jutting points, well wooded with dark firs, or clumps of those trees standing by the roadside, were agreeable features in this connection.

A brisk trot over the frozen road brought us to the end of the half-dozen miles that stretch between Somesville and the Narrows. The snow craunched beneath the horses' feet as we glided through the village street; in a moment more the driver drew up with a flourish beside the door of an inn which bears for its ensign a name advantageously known in these latitudes. A rousing fire of birchen logs blazed on the open hearth. Above the mantel were cheap prints of the presidents, from Washington to Buchanan. I was made welcome, and thought of Shenstone when he says,

"Whoe'er has travel'd life's dull round,

Whate'er his fortunes may have been,

Must sigh to think how oft he's found

Life's warmest welcome at an inn."

An island fourteen miles long and a dozen broad, embracing a hundred square miles, and traversed from end to end by mountains, is to be approached with respect. It excludes the idea of superficial observation. As the mountains bar the way to the southern shores, you must often make a long détour to reach a given point, or else commit yourself to the guidance of a deer-path, or the dry bed of some mountain torrent. In summer or in autumn, with a little knowledge of woodcraft, a well-adjusted pocket-compass, and a stout staff, it is practicable to enter the hills, and make your way as the red huntsmen were of old accustomed to do; but in winter a guide would be indispensable, and you should have well-trained muscles to undertake it.

The mountains have been traversed again and again by fire, destroying not the wood alone, but also the thin turf, the accumulations of years. The woods are full of the evidences of these fires in the charred remains of large trees that, after the passage of the flames, have been felled by tempests. At a distance of five miles the present growth resembles stubble; on a nearer approach it takes the appearance of underbrush; and upon reaching the hills you find a young forest repairing the ravages made by fire, wind, and the woodman's axe. "Fifty years ago," said Mr. Somes, "those mountains were covered with a dark growth." Cedars, firs, hemlocks, and other evergreens, with a thick sprinkling of white-birch, and now and then a clump of beeches, make the principal base for the forest of the future on Mount Desert—provided[Pg 33] always it is permitted to arrive at maturity. Hitherto the poverty or greed of the inhabitants has sacrificed every tree that was worth the labor of felling. In the neighborhood of Salisbury's Cove there are still to be seen in inaccessible places, trees destined never to feel the axe's keen edge.

Mine host of the village tavern, Daniel Somes, or "Old Uncle Daniel," as he is known far and near, is the grandson of the first settler of the name who emigrated from Gloucester, Massachusetts, and "squatted" here—"a vile phrase"—about 1760. Abraham Somes built on the little point of land in front of the tavern-door, from which a clump of shrubs may be seen growing near the spot. Other settlers came from Cape Cod, and were located at Hull's and other coves about the island. I asked my landlord if there were any family traditions relative to the short-lived settlement of the French, or traces of an occupation that might well have set his ancestors talking. He shook his gray head in emphatic negative. Had I asked him for "Tam O'Shanter" or the "Brigs of Ayr," he would have given it to me stanza for stanza.

There are few excursions to be made within a certain radius of Somesville that offer so much of variety and interest as that on the western side of the Sound, pursuing, with such wanderings as fancy may suggest, the well-beaten road to South-west Harbor. It is seven miles of hill and dale, lake and stream, with a succession of charming views constantly unfolding themselves before you. And here I may remark that the roads on the island are generally good, and easily followed.

The map may have so far introduced the island to the reader that he will[Pg 34] be able to trace the route along the side of Robinson's Mountain, which is between the road and the Sound, with two summits of nearly equal height, rising six hundred and forty and six hundred and eighty feet above it. At the right, in descending this road, is Echo Lake, a superb piece of water, having Beech Mountain at its foot. You stumble on it, as it were, unawares, and enjoy the surprise all the more for it. Broad-shouldered and deep-chested mountains wall in the reservoirs that have been filled by the snows melting from their sides. There are speckled trout to be taken in Echo Lake, as well as in the pond lying in Somesville. Of course the echo is to be tried, even if the mount gives back a saucy answer.

Next below us is Dog Mountain. It has been shut out from view until you have uncovered it in passing by the lake. Dog Mountain's eastern and highest crest is six hundred and eighty feet in the air. How much of resemblance it bears to a crouching mastiff depends in a great measure upon the imagination of the beholder:

Ham. "Do you see yonder cloud that's almost in shape of a camel?"

Pol. "By the mass, and 'tis like a camel indeed."

Ham. "Methinks it is like a weasel."

Pol. "It is backed like a weasel."

Ham. "Or like a whale?"

Pol. "Very like a whale."

Between Dog and Brown's Mountain on its eastern shore the Sound has forced its way for six or seven miles up into the centre of the island. At the southern foot of Dog Mountain is Fernald's Cove and Point, the supposed scene of the attempted settlement by the colony of Madame the Marchioness De Guercheville. Mr. De Costa has christened Brown's Mountain with the name of Mansell, from Sir Robert Mansell, vice-admiral in the times of James I. and Charles I. The whole island was once called after the knight, but there is a touch of retributive justice in recollecting that the English, in expelling the French, have in turn been expelled from its nomenclature.

Turning now to what Prescott calls "historicals" for enlightenment on the subject of the colonization of Mount Desert, it appears that upon the return of De Monts to France he gave his town of Port Royal to Jean de Poutrincourt, whose voyage in 1606 along the coast of New England will be noticed in future chapters. The projects of De Monts having been overthrown by intrigue, and through jealousy of the exclusive rights conferred by his patent, Madame De Guercheville, a "very, charitable and pious lady" of the court,[13] entered into negotiation with Poutrincourt for the founding of Jesuit missions among the savages. Finding that Poutrincourt claimed more than he could conveniently establish a right to, Madame treated directly with Du Guast, who[Pg 35] ceded to her all the privileges derived by him from Henry IV. The king, in 1607, confirmed all except the grant of Port Royal, which was reserved to Poutrincourt. The memorable year of 1610 ended the career of Henry, in the Rue de la Ferronerie. In 1611 the fathers, Père Biard and Enemond Masse, of the College d'Eu, came over to Port Royal with Biencourt, the younger Poutrincourt. During the next year an expedition under the auspices of Madame De Guercheville was prepared to follow, and, after taking on board the two Jesuits already at Port Royal, was to proceed to make a definitive settlement somewhere in the Penobscot.

The colonists numbered in all about thirty persons, including two other Jesuit fathers, named Jacques Quentin and Gilbert Du Thet.[14] The expedition was under the command of La Saussaye. In numbers it was about equal to the colony of Gosnold.

La Saussaye arrived at Port Royal, and after taking on board the fathers, Biard and Masse, continued his route. Arriving off Menan, the vessel was enveloped by an impenetrable fog, which beset them for two days and nights. Their situation was one of imminent danger, from which, if the relation of the Père Biard is to be believed, they were delivered by prayer. On the morning of the third day the fog lifted, disclosing the island of Mount Desert to their joyful eyes. The pilot landed them in a harbor on the east side of the island, where they gave thanks to God and celebrated the mass. They named the place and harbor St. Sauveur.

Singularly enough, it now fell out, as seven years later it happened to the Leyden Pilgrims, that the pilot refused to carry them to their actual destination at Kadesquit,[15] in Pentagoët River. He alleged that the voyage was completed. After much wrangling the affair was adjusted by the appearance of friendly Indians, who conducted the fathers to their own place of habitation. Upon viewing the spot, the colonists determined they could not do better than to settle upon it. They accordingly set about making a lodgment.[16]

The place where the colony was established is obscured as much by the relation of Biard as by time itself. The language of the narration is calculated to mislead, as the place is spoken of as "being shut in by the large island of Mount Desert." The Jesuit had undoubtedly full opportunity of becoming familiar with the locality, and his account was written after the dissolution of the plantation by Argall. There is little doubt they were inhabiting some part of the isle, as Champlain in general terms asserts. Meanwhile the grassy slope of Fernald's Point gains many pilgrims. The brave ecclesiastic, Du Thet, could not have a nobler monument than the stately cliffs graven by[Pg 36] lightning and the storm with the handwriting of the Omnipotent. The puny reverberations of Argall's broadsides were as nothing compared with the artillery that has played upon these heights out of cloud battlements.

During the summer of 1613, Samuel Argall, learning of the presence of the French, came upon them unawares, and in true buccaneer style. A very brief and unequal conflict ensued. Du Thet stood manfully by his gun, and fell, mortally wounded. Captain Flory and three others also received wounds. Two were drowned. The French then surrendered.

Argall's ship was called the Treasurer. Henri de Montmorency, Admiral of France, demanded justice of King James for the outrage, but I doubt that he ever received it. He alleged that, besides killing several of the colonists and transporting others as prisoners to Virginia, Argall had put the remainder in a little skiff and abandoned them to the mercy of the waves. Thus ended the fourth attempt to colonize New England.

Argall, it is asserted, had the baseness to purloin the commission of La Saussaye, as it favored his project of plundering the French more at his ease, the two crowns of England and France being then at peace. He was afterward knighted by King James, and became a member of the Council of Plymouth, and Deputy-governor of Virginia. During a second expedition to Acadia, he destroyed all traces of the colony of Madame De Guercheville. It is pretty evident he was a bold, bad man, as the more his character is scanned the less there appears in it to admire.

Brother Du Thet, standing with smoking match beside his gun, was worthy the same pencil that has illustrated the defense of Saragossa. I marvel much the event has not been celebrated in verse.

An enjoyable way of becoming acquainted with Somes's Sound is to take a wherry at Somesville and drift slowly down with the ebb, returning with the next flood. In some respects it is better than to be under sail, as a landing is always easily made, and defiance may be bidden to head winds.

One of the precipices of Dog Mountain, known as Eagle Cliff, has always attracted the attention of the artists, as well as of all lovers of the beautiful and sublime. There has been much search for treasure in the glens hereabouts, directed by spiritualistic conclaves. One too credulous islander, in his fruitless delving after the pirate Kidd's buried hoard, has squandered the gold of his own life, and is worn to a shadow.

When some one asked Moll Pitcher, the celebrated fortune-teller of Lynn, to disclose the place where this same Kidd had secreted his wealth, promising to give her half of what was recovered, the old witch exclaimed, "Fool! if I knew, could I not have all myself?" Kidd's wealth must have been beyond computation. There is scarcely a headland or an island from Montauk to Grand Menan which according to local tradition does not contain some portion of his spoil.

Much interest is attached to the shell heaps found on Fernald's Point and[Pg 37] at Sand Point opposite. There are also such banks at Hull's Cove and elsewhere. Indian implements are occasionally met with in these deposits. It is reasonably certain that some of them are of remote antiquity. Williamson states that a heavy growth of trees was found by the first settlers upon some of the shell banks in this vicinity.[17] Associated with these relics of aboriginal occupation is the print in the rock near Cromwell's Cove, called the "Indian's Foot." It is in appearance the impression of a tolerably shaped foot, fourteen inches long and two deep. The common people are not yet freed from the superstitions of two centuries ago, which ascribed all such accidental marks to the Evil One.

In my progress by the road to South-west Harbor, I was intercepted near Dog Mountain by a sea-turn that soon became a steady drizzle. This afforded me an opportunity of seeing some fine dissolving views: the sea-mists advancing, and enveloping the mountain-tops, cheated the imagination with the idea that the mountains were themselves receding. A storm-cloud, black and threatening, drifted over Sargent's Mountain, settling bodily down upon it, deploying and extending itself until the entire bulk disappeared behind an impenetrable curtain. It was like the stealthy approach and quick cast of a mantle over the head of an unsuspecting victim.

Very few were abroad in the storm, but I saw a nut-cracker and chickadee making the best of it. I remarked that under branching spruces or fir-trees the grass was still green, and the leaves of the checker-berry bright and glossy as in September. On this road admirable points of observation constantly occur from which to view the shifting contours of Beech and Western mountains, with the broad and level plateau extending along their northern baseline[Pg 38] far to the westward. Retracing with the eye this line, you see a little hamlet snugly ensconced on the hither slope of Beech Mountain, while the plateau is rounded off into the bluffs rising above Echo Lake.

South-west Harbor is usually the stranger's first introduction to Mount Desert. The approach to it is consequently invested with peculiar interest to all who know how to value first impressions. Its neighborhood is less wild and picturesque than the eastern shores of the island, but Long Lake and the western range of mountains are conveniently accessible from it; while, by crossing or ascending the Sound, avenues are opened in every direction to the surpassing charms of this favored corner of New England.

At South-west Harbor the visitor is usually desirous of inspecting the sea-wall, or cheval-de-frise of shattered rock, that skirts the shore less than three miles distant from the steamboat landing. And he may here witness an impressive example of what the ocean can do. An irregular ridge of a mile in length is piled with shapeless rocks, against which the sea beats with tireless impetuosity.

Fog is the bane of Mount Desert. Its frequency during the months of July and August is an important factor in the sum of outdoor enjoyment. Happily, it is seldom of long continuance, as genial sunshine or light breezes soon disperse it.

There is, however, a weird sort of fascination in standing on the shore in a fog. You are completely deceived as to the nearness either of objects or of sounds, though the roll of the surf is more depended upon by experienced ears than the fog-bell. In sailing near the land every one has noticed the recoil of sounds from the shore, as voices, or the beat of a steamer's paddles. Coming through the Mussel Ridge Channel one unusually thick morning, the fog suddenly "scaled up," discovering White Head in uncomfortable proximity. The light-house keeper stood in his door, tolling the heavy fog-bell that[Pg 39] we had believed half a mile away. Our pilot gave him thanks with three blasts of the steam-whistle.

Off the entrance to the Sound are several islands—Great Cranberry, of five hundred acres; Little Cranberry, of two hundred acres; and, farther inshore, Lancaster's Island, of one hundred acres. The eastern channel into the Sound is between the two last named. Duck Island, of about fifty acres, is east of Great Cranberry; and Baker's, on which is the light-house, is the outermost of the cluster.

The cranberry is indigenous to the whole extent of the Maine sea-board. It grows to perfection on the borders of wet meadows, but I have known it to thrive on the upland. The culture has been found very remunerative in localities less favored by nature, as at Cape Cod and on the New Jersey coast. Some attempts at cranberry culture have recently been made with good success at Lemoine, on the main-land, opposite Mount Desert. Blue-berries are abundant on Mount Desert. I saw one young girl who had picked enough in a week to bring her seven dollars. Formerly they were sent off the island, but they are now in good demand at the hotels and boarding-houses. In poorer families the head of it picks up a little money by shore-fishing. He plants a little patch with potatoes, dressing the land with sea-weed, which costs him only the labor of gathering it. His fire-wood is as cheaply procured from the neighboring forest or shore, and in the autumn his wife and children gather berries, which are exchanged for necessaries at the stores.

At the extreme southerly end of Mount Desert is Bass Harbor, with three islands outlying. It is landlocked, and a well-known haven of refuge.[Pg 40]

"You should have seen that long hill-range,

With gaps of brightness riven—

How through each pass and hollow streamed

The purpling light of heaven—"

Whittier.

Having broken the ice a little with the reader, I shall suppose him present on the most glorious Christmas morning a New England sun ever shone upon. "A green Christmas makes a fat church-yard," says an Old-country proverb; this was a white Noël, cloudless and bright. I saw that the peruke of my neighbor across the Sound, Sargent's Mountain, had been freshly powdered during the night; that the rigging of the ice-bound craft[Pg 41] harbored between us was incased in solid ice, reflecting the sunbeams like burnished steel. The inscription on mine host's sign-board was blotted out by the driving sleet; the brown and leafless trees stood transfigured into objects of wondrous beauty. I heard the jingle of bells in the stable-yard and the stamping of feet below stairs, and then

"I heard nae mair, for Chanticleer

Shook off the pouthery snaw,

And hail'd the morning with a cheer,

A cottage-rousing craw."

The roads from Bar Harbor and from North-east Harbor unite within a short distance of Somesville, and enter the village together. Within these highways is embraced a large proportion of those picturesque features for which the island is famed. In this area are the highest mountains, the boldest headlands, the deepest indentations of the shores. It is not for nothing, therefore, that Bar Harbor has become a favorite rendezvous of the throngs

"That seek the crowd they seem to fly."

On Christmas-day the road to Bar Harbor was an avenue of a winter palace more sumptuous than that by the Neva. Every spray of the dark evergreen trees was heavily laden with a light snow that plentifully besprinkled us in passing beneath the often overreaching branches. The stillness was unbroken. Blasted trees—gaunt, withered, and hung with moss like rags on the shrunken limbs of a mendicant—were now incrusted with ice-crystals, that glittered like lustres on gigantic candelabra. On the top of some rounded hill there sometimes was standing the bare stem of a blasted pine, where it shone like the spike on a grenadier's helmet. It was a scene of enchantment.

I saw frequent tracks where the deer had come down the mountain and crossed the road, sometimes singly, sometimes in pairs, and in search, no doubt, of water. The foot-prints of foxes, rabbits, and grouse were also common. During the day I met an islander who told me he had shot a fat buck only a day or two before, and that many deer were still haunting the mountains. Formerly, but so long ago that only tradition preserves the fact, there were black bear and moose; and traces of beaver are yet to be seen in their dams and houses. Red foxes and mink, and occasionally the black fox, greatly valued for its fur, are taken by the hunters. In order to make the roads interesting to nocturnal travelers, rumor was talking of a panther and a wolf that had been seen within a short time.

In the day when these coasts were stocked with beaver, its skin was the common currency of the country, as well of the Indians as of the whites. It was greatly prized in Europe, and constituted the wealth of the savages of northern New England, who were wholly unacquainted with wampum until[Pg 42] it was introduced among them by the Plymouth trading-posts on the Penobscot and Kennebec.

The wigwam of a rich chief would be lined with beaver-skins, and, if he were very rich, his guests were seated on packs of it. Then, as now, a suitor was not the less acceptable if he came to his mistress with plenty of beaver. It was the Indians' practice to kill only two-thirds of the beaver each season, leaving a third for increase. The English hunters killed all they found, rapidly exterminating an animal which the Indian believed to be possessed of preternatural sagacity.

Our road, after crossing a northern spur of Sargent's Mountain, which lifts itself more than a thousand feet above the sea, led on over a succession of hills. Beyond Sargent's, Green Mountain stood unveiled, with what seemed the tiniest of cottages perched on its summit. Ere long Eagle Lake lay outstretched at the right, but it was in the trance of winter. The painter, Church, whose favorite ground lay about due south, christened the lake, doubtless with a palmful of water from its own baptismal font. The roadway is thrown across its outlet where the timbers of an old mill, that some time ago had gorged itself with the native forest, lay rotting and overthrown.

Green Mountain overpeers all the others. On its summit you are fifteen hundred and thirty-five feet higher than the sea. On this account it was selected as a landmark for the survey of the neighboring coasts. It is not difficult of ascent, as the mountain road built by the surveyors is considered practicable for carriages nearly or quite to the top. I had anticipated ascending it, but the new-fallen snow rendered walking difficult, and I was forced to content myself with viewing it from all sides of approach.

An acquaintance with the sierras of either half of the continent exercises a restraining influence in presence of an upheaval comparatively slight, yet it is only in a few favored instances that one may stand on the summits of very high mountains and look down upon the sea. New England, indeed, boasts greater elevations at some distance from her sea-coast, among which the Mount Desert peaks would appear dwarfed into respectable hills. On a clear day, and under conditions peculiarly favorable, a distant glimpse of Katahdin and of Mount Washington may be had from the crest of Green Mountain. In summer the little house is open for the refreshment of weary but adventurous pilgrims.

Here I would observe that the island nomenclature is painfully at variance with whatever is suggestive of felicitous rapport with its natural characteristics. The name of Mount Desert, it is true, is singularly appropriate; but then it was given by a Frenchman with an eye for truth in picturesqueness. In the year 1796, when the north half of the island was formed into a township, it was called, with sublimated irony, Eden. Green Mountain is not more green than its neighbors. At the Ovens I saw plenty of yeast, but not enough to leaven the name. Schooner Head is not more apposite.

Just before coming into Bar Harbor there is an excellent opportunity of observing the cluster of islands to which it owes existence. These are the Porcupine group, and beyond, across a broad bay, the Gouldsborough hills appeared in a Christmas garb of silvery whiteness. The Porcupine Islands, four in number, lie within easy reach of the shore, Bar Island, the nearest, being connected with the main-land at low ebb. On Bald Porcupine General Fremont has pitched his head-quarters. It was the sea that was fretful when I looked at the islands, though they bristled with erected pines and cedars.

The village at Bar Harbor is the sudden outgrowth of the necessities of a population that comes with the roses, and vanishes with the first frosts of autumn. It has neither form nor comeliness, though it is admirably situated for excursions to points on the eastern and southern shores of the island as far as Great Head and Otter Creek. A new hotel was building, notwithstanding the last season had not proved as remunerative as usual. I saw that pure water was brought to the harbor by a wooden aqueduct that crossed the valley on trestles, after the manner practiced in the California mining regions, and there called a flume. There is a beach, with good bathing on both sides of the landing, though the low temperature of the water in summer is hardly calculated for invalids.

From Bar Harbor, a road conducts by the shore, southerly, as far as Great Head, some five miles distant. After following this route for a long mile,[Pg 44] as it seemed, it divides, the road to the right leading on five miles to Otter Creek, and thence to North-east Harbor, seven miles beyond. Excursions to Great Head, and to Newport Mountain and Otter Creek, should occupy separate days, as the shores are extremely interesting, and the scenery unsurpassed in the whole range of the island.

In pursuing his explorations at or near low-water mark, it will be best for[Pg 45] the tourist to begin a ramble an hour before the tide has fully ebbed. The tides on this coast ordinarily rise and fall about twelve feet, and in winter, as I saw, frequently eighteen feet. Hence the advance and retreat of the waves is not only rapid, but leaves a broader margin uncovered than in Massachusetts Bay, where there is commonly not more than eight feet of rise and fall. In many places along the arc of the shore stretching between Bar Harbor and Great Head, the ascent to higher ground is, to say the least, difficult, and, in some instances, progress is forbidden by a beetling cliff or impassable chasm. As time is seldom carefully noted when one is fairly engaged in such investigations, it is always prudent first to know your ground, and next to keep a wary eye upon the stealthy approach of the sea.

There is a pleasant ramble by the shore to Cromwell's Cove; but here onward movement is arrested by a cliff that turns you homeward by a cross-path through the fields to the road, after having whetted the appetite for what is yet in reserve.

Schooner Head is reached by this road in about four miles from Bar Harbor, and three from the junction of the Otter Creek road. I walked it easily in an hour. The way is walled in on the landward side by the abrupt precipices of Newport Mountain, in the sheer face of which stunted firs are niched here and there. Very much they soften the hard, unyielding lines and cold[Pg 46] gray of the crags; the eye lingers kindly on their green chaplets cast about the frowning brows of wintry mountains. This morning all were Christmas-trees, and the ancients of the isle hung out their banners to greet the day.

Emerging from the woods at a farm-house at the head of a cove, a foot-path leads to the promontory at its hither side. It is thrust a little out from the land, sheltering the cove while itself receiving the full onset of the sea. An intrusion of white rock in the seaward face is supposed by those of an imaginative turn to bear some resemblance to a schooner; and, in order to complete the similitude, two flag-staffs had been erected on the top of the cliff. At best, I fancy it will be found a phantom ship to lure the mariner to destruction.

I did not find Schooner Head so remarkable for its height as in the evidences everywhere of the crushing blows it has received while battling with storms. "Hard pounding this, gentlemen; but we shall see who can pound longest," said the Iron Duke at Waterloo. Here are the rents and ruins of ceaseless assault and repulse. The ocean is slowly but steadily advancing on both sides of the continent; perchance it is, after all, susceptible of calculation how long the land shall endure.

I clambered among the huge blocks of granite that nothing less than steam could now have stirred, although they had once been displaced by a few drops of water acting together. A terrible rent in the east side of the cliff is locally known as the Spouting Horn. Down at its base the sea has worn through the rock, leaving a low arch. At the flood, with sufficient sea on, and an off-shore wind, a wave rolls in through the cavity, mounts the escarpment, and leaps high above the opening with a roar like the booming of heavy ordnance. These natural curiosities are not unfrequent along the[Pg 47] coast. There is one of considerable power at Cape Arundel, Maine, that I have heard when two miles from the spot. Unfortunately for the tourist, these grand displays are usually in storms, when few care to be abroad; undoubtedly, the outward man may be protected and the inward exalted at such times. Some of the more adventurous go through the Horn: I went around it.

I saw here a few ruminant sheep gazing off upon the sea. What should a sheep see in the ocean?

On the farther side of the cove is a sea-cavern that has the reputation of being the finest on the island. Within its gloomy recesses are rock pools of rare interest to the naturalist. In proper season they will be found inhabited by the sea-anemone and other and more debatable forms of animal life. Some of these aquaria I have seen are of marvelous beauty, recalling the lines,

"Full many a gem of purest ray serene

The dark unfathomed caves of ocean bear."

Lined with mother-of-pearl and scarlet mussels, resting on beds of soft sponge or purple moss-tufts, these fairy grottoes are the favorite retreat of King Crab and his myrmidons, of the star-fish and sea-urchin. Twice in every twenty-four hours the basins are refilled with pure sea-water, than which nothing can be more transparent. Strange that these rugged crags, where the grasp of man would be loosened by the first wave, should be instinct with life! It required some force to detach a mussel from its bed, and you must have recourse to your knife to remove the barnacles with[Pg 48] which the smoother rocks are incrusted. John Adams, when he first saw the sea-anemone, compared it, in figure and feeling, to a young girl's breast.

Mount Desert has been familiar to two of the greatest of American naturalists. When Audubon was preparing his magnificent "Birds of America," he visited the island, and I have no doubt the report of his rifle was often heard echoing among the mountains or along the shores. Agassiz was also here, interrogating the rocks, rapping their stony knuckles with his hammer, or pressing their gaunt ribs with playful familiarity. Audubon died in 1851. Agassiz is more freshly remembered by the present generation, to whom he made the pathway of Natural Science bright by his genius, and pleasant, by his genuine, whole-hearted bonhomie.

In 1858 the French Government devoted itself, with extreme solicitude, to the reorganization of the administration of the Museum of Natural History of the Jardin des Plantes at Paris. It appears that, in spite of a first refusal, several times repeated, Agassiz at length consented to accept the direction of the museum. The Emperor, who had formed a personal acquaintance with the celebrated naturalist during his sojourn in Switzerland, pursued with customary pertinacity his favorite idea of alluring M. Agassiz to Paris. He was offered a salary of twenty-five thousand francs; and it was understood he was promised, besides, elevation to the dignity of senator, of which the appointments were worth twenty-five thousand francs more.

I have thought it fitting to give Agassiz's own report of his first introduction to an American public:

"When I came to Boston," said he, "the first course which I gave had five thousand auditors, and I was obliged to divide them into two sections of twenty-five hundred each, and to repeat each lesson. This course was given in the large hall of the Tremont Temple."

"Do you think," he was asked, "that in such a crowd it was the fashion or the desire for instruction which dominated?"

"No doubt," he replied, "it was a serious desire for instruction. I have plenty of proofs of it coming from persons belonging to the lower classes. For instance, it is usual here to accord to persons who go out to service full liberty after a certain hour in the evening, solely to go to the course of lectures; that is made a part of the agreement. A lady who had a very strong desire to hear me, told me that it was impossible for her to do so. Her cook was the first informed of my announcement, took the initiative, and obtained her promise of liberty for the hour of the evening when I taught, and left her mistress to take care of the house alone. On her return she explained very clearly what I had said."

The slow sale of Agassiz's works in Europe decided him to pass fifteen months in the United States; and the revolution of 1848 changed this intention into a purpose of permanent residence. Agassiz was tall, corpulent, bent, rather by continual study than with age. His forehead was broad, high, and a little retreating; his countenance conspicuously Swiss, by the largeness of his features, the gravity and benevolence of his expression. His hair was gray, and little abundant. He spoke German and English with facility, but had to some extent unlearned his French. Although his conversation was without volubility, when he grew animated in talking upon great questions his expression became noble and majestic. "There was in him a remarkable force of thought and will. He appeared like a man who makes haste slowly; but notwithstanding the adage, no one can withhold an involuntary astonishment at the great works he has been able to achieve." Agassiz belonged to the noblesse of science and of literature. When such men die they can not be said to leave legitimate successors.

Mount Desert has itself produced a man of marked usefulness in David Wasgatt Clark, D.D., a Wesleyan divine, who was elected bishop in 1864. He accomplished extensive literary labors, was intrusted with high and responsible positions, and although a puny boy, the jest of his companions of a more robust mould, completed nearly three-score years of a laborious and eventful life.

From Schooner Head I pursued my way by the road to Great Head. And while en route I should not forget the Lynam Homestead, to which Cole, Church, Gifford, Hart, Parsons, Warren, Bierstadt, and others renowned in American art have from time to time resorted to enrich their studios from the abounding wealth of the neighborhood.

One of the first artists to come to the island was Fisher. Church, whose name is associated with its rediscovery, did not always come for work. On one occasion, as leader of a merry party, he was lost on Beech Mountain, and passed the night there. With rare prevision he had provided an axe, with plenty of robes and wraps. At the foot of the mountain the carriage was sent back to the village. Church was too good a woodman not to use his axe to make a shanty of boughs, while the robes, when spread upon fragrant heaps of spruce, made excellent couches for the laughing girls that were under his protection. Meanwhile consternation reigned at Somesville. Messengers were sent hither and thither in haste; but no tidings arrived of the absent ones until the next morning, when they entered the village as if nothing unusual had happened.

Great Head is easily found. The road we have been pursuing comes to an abrupt ending at a house within a short half-mile of it. Follow the shore backward toward Schooner Head, and you will stand in presence of the boldest headland in all New England. I saw that no foot-print but my own had lately passed that way. There was something in thus having it all to one's self.

To appreciate Great Head one must stand underneath it; but the descent, always difficult, was rendered perilous by the newly-formed ice. By dint of perseverance I at last stood upon the ledge beneath, that extends out like a platform for some distance toward deep water. It was the right stage of the tide. I looked up at the face of the cliff. It was bearded with icicles, like the Genius of Winter. Along the upper edge appeared the interlacing roots of old trees grasping the scanty soil like monster talons. Stunted birches, bent by storms, skirted its brow, and at sea add to its height. From top to bottom the face of the cliff is a mass of hard granite, overhanging its foundations in impending ruin, shivered and splintered as if torn by some tremendous explosion. I could only think of the last sketch of Delaroche.

The sea rolls in great waves that overwhelm every thing within their reach. More than once I started back at the approach of one of them. Just outside the first line of breakers rode a flock of wild fowl, and occasionally the mournful cry of a loon, or shriller scream of a sea-gull, mingled with the roar of the surf. Farther out, at the distance of a mile, a wicked-looking rock and ledge was flinging off the seas, flecking its tawny flanks with foam, like a war-horse impatiently champing at his bit.

Looking off from Great Head to the eastward, the main-land is perceived

trending away until it loses itself in the ocean. At the extremity of

this land is Schoodic Point and Mountain, with Mosquito Harbor indenting

it. The water between is not the true "Baye Françoise" of Champlain,

Lescarbot, and others. The appellation belongs of right to the Bay of

Fundy, perpetuating as it does the misadventure of Nicolas Aubri, one of

the company of De Monts, who was lost in the woods there. As this is not

the only historic anachronism[Pg 51]

[Pg 52]

[Pg 53] by many that may be met with on our

coasts, I do not propose to quarrel with it, the less that a Frenchman

was the first white here. The name has been current for about a century,

though on old French maps it is found to lie farther east.