The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Wishing Well, by Mildred A. Wirt This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Wishing Well Author: Mildred A. Wirt Release Date: December 18, 2010 [EBook #34689] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WISHING WELL *** Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Brenda Lewis and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

By

MILDRED A. WIRT

Author of

MILDRED A. WIRT MYSTERY STORIES

TRAILER STORIES FOR GIRLS

Illustrated

CUPPLES AND LEON COMPANY

Publishers

NEW YORK

PENNY PARKER

MYSTERY STORIES

Large 12 mo. Cloth Illustrated

TALE OF THE WITCH DOLL

THE VANISHING HOUSEBOAT

DANGER AT THE DRAWBRIDGE

BEHIND THE GREEN DOOR

CLUE OF THE SILKEN LADDER

THE SECRET PACT

THE CLOCK STRIKES THIRTEEN

THE WISHING WELL

SABOTEURS ON THE RIVER

GHOST BEYOND THE GATE

HOOFBEATS ON THE TURNPIKE

VOICE FROM THE CAVE

GUILT OF THE BRASS THIEVES

SIGNAL IN THE DARK

WHISPERING WALLS

SWAMP ISLAND

THE CRY AT MIDNIGHT

COPYRIGHT, 1942, BY CUPPLES AND LEON CO.

The Wishing Well

PRINTED IN U. S. A.

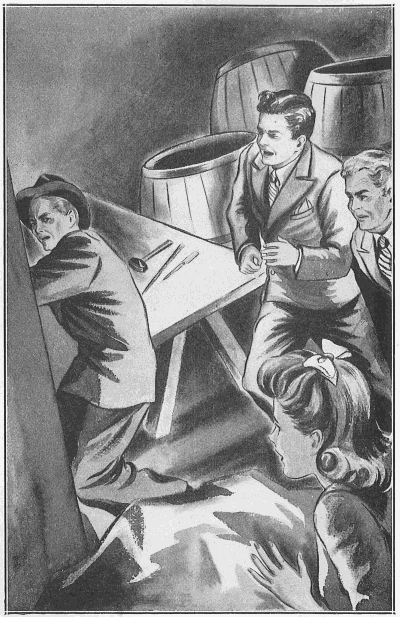

HE WHEELED AND RAN OUT THE OPEN DOOR.

“The Wishing Well” (See Page 199)

At her desk in the assembly room of Riverview High School, Penny Parker sat poised for instant flight. Her books had been stacked away, and she awaited only the closing bell to liberate her from a day of study.

“Now don’t forget!” she whispered to her chum, Louise Sidell, who occupied the desk directly behind. “We start for the old Marborough place right away!”

The dismissal bell tapped. Penny bolted down the aisle and was one of the first to reach the door. However, hearing her name called, she was forced to pause.

“Penelope, will you wait a moment please?” requested the teacher in charge of assembly.

“Yes, Miss Nelson,” Penny dutifully responded, but she shot her chum a glance of black despair.

“What have you done now?” Louise demanded in an accusing whisper.

“Not a thing,” muttered Penny. “About ten minutes ago I clipped Fred Green with a paper ball, but I don’t think she saw me.”

“Get out of it as fast as you can,” Louise urged. “Unless we start for the Marborough place within half an hour we’ll have to postpone the trip.”

While the other pupils filed slowly from the room, Penny slumped back into her seat. She was a tall, slim girl with mischievous blue eyes which hinted of an active mind. Golden hair was accented by a brown sweater caught at the throat with a conspicuous ornament, a weird looking animal made of leather.

“Penelope, I don’t suppose you know why I asked you to remain,” observed the teacher, slowly coming down the aisle.

“Why, no, Miss Nelson.” Penny was far too wise to make damaging admissions.

“I want to talk to you about Rhoda Wiegand.”

“About Rhoda?” Penny echoed, genuinely surprised. The girl was a new student at Riverview, somewhat older than the members of her class, and lived in a trailer camp at the outskirts of the city.

Miss Nelson seated herself at a desk opposite Penny, thus indicating that she meant the talk to be friendly and informal.

“Penelope,” she resumed, “you are president of the Palette Club. Why has Rhoda never been taken in as a member? She is one of our most talented art students.”

“Some of the girls don’t seem to like Rhoda very well,” Penny answered, squirming uncomfortably. “We did talk about taking her into the club, but nothing came of it.”

“As president of the organization, couldn’t you arrange it?”

“I suppose so,” Penny admitted, frowning thoughtfully.

“Why do the girls dislike Rhoda?”

“There doesn’t seem to be any special reason for it.”

“Her poverty, perhaps?”

“I don’t think it’s that,” Penny defended the club members. “Rhoda is so quiet that the girls have never become acquainted with her.”

“Then I suggest that they make an immediate effort,” Miss Nelson ended the interview. “The Palette Club has no right to an existence unless it welcomes members with real art talent.”

A group of girls awaited Penny when she reached the locker room. They eagerly plied her with questions as to why she had been detained by the teacher.

“I’ll tell you later,” Penny promised.

At the other side of the room Rhoda Wiegand was removing a coat from her locker. A sober-faced girl of seventeen, she wore a faded blue dress which seemed to draw all color from her thin face. Knowing that she was not well liked, she seldom spoke or forced herself upon the other students.

“Rhoda,” began Penny, paying no heed to the amazed glances of her friends, “the Palette Club is having a meeting this afternoon at the old Marborough place. Why not come with us?”

The older girl turned quickly, a smile of surprise and pleasure brightening her face.

“Oh, I should love to go, only I don’t think—” Hesitating, she gazed at the other girls who were eyeing her in a none too friendly way.

Penny gave Louise Sidell a little pinch. Her chum, understanding what was expected, said with as much warmth as she could: “Yes, do come, Rhoda. We plan to sketch the old wishing well.”

“I have enough drawing material for both of us,” Penny added persuasively.

“If you really want me, of course I’ll come!” Rhoda accepted, her voice rather tremulous. “I’ve heard about the Marborough homestead, and always longed to see it.”

A group of subdued girls gathered their belongings from the lockers, preparing to leave the school grounds. No one understood why Penny had invited Rhoda to attend the outing, and the act had not been a popular one.

Boarding a bus, the twelve members of the Palette Club soon reached the end of the line, and from there walked a quarter of a mile into the country. Penny and Louise chose Rhoda as their companion, trying to make her feel at ease. Conversation became rather difficult and they were relieved when, at length, they approached their destination.

“There’s the old house,” Penny said, indicating a steep pitched roof-top which could be seen rising above a jungle of tall oaks. “It’s been unoccupied for at least ten years now.”

The Marborough homestead, a handsome dwelling of pre-Civil war day, long had been Riverview’s most outstanding architectural curiosity. Only in a vague way was Penny familiar with its history. The property had been named Rose Acres and its mistress, Mrs. James Marborough, had moved from the city many years before, allowing the house to stand unpainted and untended. Once so beautifully kept, the grounds had become a tangle of weeds and untrimmed bushes. Even so, the old plantation home with its six graceful pillars, retained dignity and beauty.

Entering the yard through a space where a gate once had stood, the girls gazed about with interest. Framed in a clump of giant azaleas was the statue of an Indian girl with stone feathers in her hair. Beyond, they caught a glimpse of the river which curved around the south side of the grounds in a wide bend.

“Where is the old wishing well?” Rhoda inquired. “I’ve heard so much about it.”

“We’re coming to it now,” Penny replied, leading the way down an avenue of oak trees.

Not far from the house stood the old-fashioned covered well. Its base was of cut stone and on a bronze plate had been engraved the words: “If you do a good deed, you can make a wish and it will come true.”

“Some people around Riverview really believe that this old well has the power to make wishes come true,” Louise Sidell remarked, peering at her reflection mirrored in the water far below. “In the past years when Mrs. Marborough lived here, it had quite a reputation.”

“The water is still good if you don’t mind a few germs,” Penny added with a laugh. “I see that someone has replaced the bucket. There was none here the last time I came.”

By means of the long sweep, she lowered the receptacle and brought it up filled with water.

“Make a wish, Penny,” one of her friends urged. “Maybe it will come true.”

“Everyone knows what she’ll ask for!” teased Louise. “Her desires are always the same—a bigger weekly allowance!”

Penny smiled as she drew a dipper of water from the wooden bucket.

“How about the good deed?” she inquired lightly. “I’ve done nothing worthy of a demand upon this old well.”

“You helped your father round up a group of Night Riders,” Louise reminded her. “Remember the big story you wrote for the Riverview Star which was titled: The Clock Strikes Thirteen?”

“I did prevent Clyde Blake from tricking a number of people in this community,” Penny acknowledged. “Perhaps that entitles me to a wish.”

Drinking deeply from the dipper, she poured the last drops into the well, watching as they made concentric circles in the still water below.

“Old well, do your stuff and grant my wish,” she entreated. “Please get busy right away.”

“But what is your wish, Penny?” demanded one of the girls. “You have to tell.”

“All right, I wish that this old Marborough property could be restored to its former beauty.”

“You believe in making hard ones,” Louise laughed. “I doubt that this place ever will be fixed up again—at least not until after the property changes hands.”

“It’s Rhoda’s turn now,” Penny said, offering the dipper to her.

The older girl stepped to the edge of the well, her face very serious.

“Do you think wishes really do come true?” she asked thoughtfully.

“Oh, it’s only for the fun of it,” Louise responded. “But they do say that in the old days, this well had remarkable powers. At least many persons came here to make wishes which they claimed came true. I couldn’t believe in it myself.”

Rhoda stood for a moment gazing down into the well. Drinking from the dipper, she allowed a few drops to spatter into the deep cavern below.

“I wish—” she said in a low, tense voice—“I wish that some day Pop and Mrs. Breen will be repaid for looking after my brother and me. I wish that they may have more money for food and clothes and a few really nice things.”

An awkward, embarrassing silence descended upon the group of girls. Everyone knew that Rhoda and her younger brother, Ted, lived at a trailer camp with a family unrelated to them, but not even Penny had troubled to learn additional details. From Rhoda’s wish it was apparent to all that the Breens were in dire poverty.

“It’s your turn now, Louise,” Penny said quickly.

Louise accepted the dipper. Without drinking, she tossed all the water into the well, saying gaily:

“I wish Penny would grow long ears and a tail! It would serve her right for solving so many mystery cases!”

The other girls made equally frivolous wishes. Thereafter, they abandoned fun for serious work, getting out their sketching materials. Penny and Louise began to draw the old well, but Rhoda, intrigued by the classical beauty of the house, decided to try to transfer it to paper.

“You do nice work,” Penny praised, gazing over the older girl’s shoulder. “The rest of us can’t begin to match it.”

“You may have the sketch when I finish,” Rhoda offered.

As she spoke, the girls were startled to hear a commotion in the bushes behind the house. Chickens began to cackle, and to their ears came the sound of pounding feet.

Suddenly, from the direction of the river, a young man darted into view, pursued by an elderly man who was less agile. To the girls, it was immediately apparent why the youth was being chased, for he carried a fat hen beneath his arm, and ran with hat pulled low over his face.

“A chicken thief!” Penny exclaimed, springing to her feet. “Come on, girls, let’s head him off!”

Seeing the group of girls by the wishing well, the youth swerved, and fled in the opposite direction. Darting into the woods, he ran so swiftly that Penny realized pursuit would be futile.

“Who was he?” she questioned the others. “Did any of you recognize him?”

“I’m sure I’ve seen him somewhere,” Louise Sidell declared. “Were you able to see his face, Rhoda?”

The older girl did not answer, for at that moment the man who had pursued the boy ran into the yard. Breathing hard, he paused near the well.

“Did you see a boy come through here?” he asked abruptly. “The rascal stole one of my good layin’ hens.”

“We saw him,” Penny answered, “but I’m sure you’ll never overtake him now. He ran into the woods.”

“Reckon you’re right,” the man muttered, seating himself on the stone rim of the wishing well. “I’m tuckered.” Taking out a red-bandana handkerchief, he wiped perspiration from his forehead.

Penny thought that she recognized the man as a stonecutter who lived in a shack at the river’s edge. He was a short, muscular individual, strong despite his age, with hands roughened by hard labor. His face had been browned by wind and sun; gray eyes squinted as if ever viewing the world with suspicion and hate.

“Aren’t you Truman Crocker?” Penny inquired curiously.

“That’s my tag,” the stonecutter answered, drawing himself a drink of water from the well. “What are you young ’uns doing here?”

“Oh, our club came to sketch,” Penny returned. “You live close by, don’t you?”

“Down yonder,” the man replied, draining the dipper in a thirsty gulp. “I been haulin’ stone all day. It’s a hard way to make a living, let me tell you. Then I come home to find that young rascal making off with my chickens!”

“Do you know who he was?” asked Louise.

“No, but this ain’t the first time he’s paid me a visit. Last week he stole one of my best Rhode Island Reds. I’m plumb disgusted.”

Rhoda abruptly arose from the grass, gathering together her sketching materials. As if to put an end to the conversation, she remarked:

“It will soon be dark, girls. I think I should start home.”

“We’ll all be leaving in a few minutes,” Penny replied. “Let’s look around a bit more though, before we go.”

“You won’t see nothin’ worth lookin’ at around here,” the stonecutter said contemptuously. “This old house ain’t much any more. There’s good lumber in it though, and the foundation has some first class stone.”

“You speak as if you had designs on it,” Penny laughed. “It would be a shame to tear down a beautiful old house such as this.”

“What’s it good for?” the man shrugged. “There ain’t no one lived here in ten or twelve years. Not since the old lady went off.”

“Did you know Mrs. Marborough?”

“Oh, we said howdy to each other when we’d meet, but that was the size of it. The old lady didn’t like me none and I thought the same of her. She never wanted my chickens runnin’ over her yard. Ain’t it a pity she can’t see ’em now?”

With a throaty sound, half chuckle, half sneer, the man arose and walked with the girls around the house.

“If you want to look inside, there’s a shutter off on the east livin’ room window,” he informed. “Everything’s just like the old lady left it.”

“You don’t mean the furniture is still in the house!” Rhoda exclaimed incredulously.

“There ain’t nothing been changed. I never could figure why someone didn’t come in an’ haul off her stuff, but it’s stood all these years.”

Their curiosity aroused, the girls hastened to the window that Truman Crocker had mentioned. Flattening her face against the dirty pane, Penny peered inside.

“He’s right!” she announced. “The furniture is still covered by sheets! Why, that’s funny.”

“What is?” inquired Louise impatiently.

“There’s a lady’s hat lying on the table!”

“It must be quite out of style by this time,” Louise laughed.

“A new hat,” Penny said with emphasis. “And a purse lying beside it!”

At the other side of the house, an outside door squeaked. Turning around, the group of girls stared almost as if they were gazing at a ghost. An old lady in a long blue silk dress with lace collar and cuffs, stepped out onto the veranda. She gazed beyond the girls toward Truman Crocker who leaned against a tree. Seeing the woman, he straightened to alert attention.

“If it ain’t Priscilla Marborough!” he exclaimed. “You’ve come back!”

“I certainly have returned,” the old lady retorted with no friendliness in her voice. “High time someone looked after this place! While I’ve been away, you seemingly have used my garden as a chicken run!”

“How did I know you was ever coming back?” Crocker demanded. “Anyhow, the place has gone to wrack and ruin. A few chickens more nor less shouldn’t make no difference.”

“Perhaps not to you, Truman Crocker,” Mrs. Marborough returned with biting emphasis. “You know I am home now, so I warn you—keep your live stock out of my garden!”

Penny and her friends shared the old stonecutter’s chagrin, for they too were trespassers. Waiting until the woman had finished lecturing Crocker, they offered an apology for the intrusion.

“We’re very sorry,” Penny said, speaking for the others. “Of course we never dreamed that the house was occupied or we wouldn’t have peeped through the window. We came because we wanted to sketch the old wishing well and your lovely home.”

Mrs. Marborough came down the steps toward the girls.

“I quite understand,” she said in a far milder tone than she had used in speaking to the stonecutter. “You may look around as much as you wish. But first, tell me your names.”

One by one they gave them, answering other questions which the old lady asked. She kept them so busy that they had no opportunity to interpose any of their own. But at length Penny managed to inquire:

“Mrs. Marborough, are you planning to open up your home again? Everyone would be so happy if only you should decide to live here!”

“Happy?” the old lady repeated, her eyes twinkling. “Well, maybe some people would be, and others wouldn’t.”

“Rose Acres could be made into one of the nicest places in Riverview,” declared Louise.

“That would take considerable money,” replied Mrs. Marborough. “I’ve not made any plans yet.” Abruptly she turned to face Truman Crocker who was staring at her. “Must you stand there gawking?” she asked with asperity. “Get along to your own land, and mind, don’t come here again. I’ll not have trespassers.”

“You ain’t changed a bit, Mrs. Marborough, not a particle,” the stonecutter muttered as he slowly moved off.

Truman Crocker’s dismissal had been so curt that Penny and her friends likewise started to leave the grounds.

“You needn’t go unless you want to,” Mrs. Marborough said, her tone softening again. “I never could endure that no-good loafer, Truman Crocker! All the stepping stones are gone from my garden, and I have an idea what became of them!”

The group of girls hesitated, scarcely knowing what to do or say. As the silence became noticeable, Penny tried to make conversation by remarking that she and her friends had been especially interested in the old wishing well.

“Is it true that wishes made there have come true?” Rhoda Wiegand interposed eagerly.

“Yes and no,” the old lady smiled. “Hundreds of wishes have been made at the well over the years. A surprising number of the worthwhile ones have been granted, so folks say. Tell me, did you say your name is Rhoda?”

“Why, yes,” the girl responded, surprised that the old lady had remembered. “Rhoda Wiegand.”

“Wiegand—odd, I don’t recall the name. Have your parents lived many years in Riverview?”

“My mother and father are dead, Mrs. Marborough. My brother and I haven’t any living relatives. Mr. and Mrs. Breen took us in so we wouldn’t have to go to an orphans’ home. They have three children of their own, and I’m afraid we’re quite a burden.”

“Where do the Breens live, my child?”

“We have a trailer at the Dorset Tourist Camp.”

“I’ve always thought I should enjoy living that way,” Mrs. Marborough declared. “Big houses are entirely too much work. If I decide to clean up this place, it will take me weeks.”

“Can’t we all help you?” suggested Louise impulsively. More than anything else she longed to see the interior of the quaint old house.

“Thank you, my dear, but I shall require no assistance,” Mrs. Marborough replied somewhat stiffly. Obviously dismissing the girls, she added: “Do come again whenever you like.”

During the bus ride to Riverview, the members of the Palette exchanged comments, speculating upon why the old lady had returned to the city after such a lengthy absence. One by one they alighted at various street corners until only Rhoda, Penny, and Louise remained.

“Rhoda, you’ll have a long ride to the opposite side of the city,” Penny remarked as she and Louise prepared to leave the bus. “Why not get off here and let me drive you home in my car? It won’t take long to get it from the garage.”

“Oh, that would be too much trouble,” Rhoda protested.

“I want to do it,” Penny insisted. Taking the girl by the elbow, she steered her to the bus exit. To Louise she added: “Why not come along with us?”

“Perhaps I will, if you’ll drive your good car—not Leaping Lena.”

Penny was the proud possessor of two automobiles, one a handsome maroon sedan, the other a dilapidated, ancient “flivver” which had an unpleasant habit of running only when fancy dictated. How she had obtained two cars was a story in itself—in fact, several of them. The maroon model, however, had been the gift of Penny’s devoted father, Anthony Parker, publisher of Riverview’s leading daily newspaper, The Star. He had presented the car to her in gratitude because she had achieved an exclusive story for his paper, gaining astounding evidence by probing behind a certain mysterious Green Door.

Delighted with the gift, Penny promptly sold Leaping Lena only to become so lonesome for her old friend that she had bought it back from a second-hand dealer. In towing the car home she was involved in an accident, and there followed a chain of amazing events which ultimately brought the solution of a mystery case known as Clue of the Silken Ladder. Leaping Lena and trouble always went together, according to Louise, but Penny felt that every one of her adventures had been worth while.

“I don’t mind taking the maroon car,” she replied to her chum. “In fact, Lena hasn’t been running so well lately. I think she has pneumonia of the carburetor.”

“Or maybe it’s just old age sneaking up on her!” Louise added with a teasing laugh.

Reaching the Parker home, Penny ran inside to tell Mrs. Weems, the housekeeper, that she was taking Rhoda to the trailer camp. Returning a moment later, she backed the maroon car from the garage with dazzling skill and further exhibited her prowess as a driver.

“Penny always handles an automobile as if she were enroute to a three-alarm fire!” Louise assured Rhoda. “A reporter at the Star taught her how to drive.”

Presently, the car arrived at the Dorset Tourist Camp, rolling through an archway entrance into a tree-shaded area.

“Our trailer is parked over at the north side,” Rhoda said, pointing to a vehicle with faded brown paint.

Penny stopped the car beneath a large maple tree. Immediately three small children who had been playing close by, rushed up to greet Rhoda. Their hands and faces were very dirty, frocks unpressed and torn, and their hair appeared never to have made contact with comb or brush.

“Are these the Breen youngsters?” inquired Louise.

“Yes,” Rhoda answered, offering no apology for the way the children looked. “This is Betty, who is seven. Bobby is five, and Jean is our baby.”

Penny and Louise had no intention of remaining at the camp, but before they could drive away, Mrs. Breen stepped from the trailer. She came at once to the car, and Rhoda introduced her.

“I’ve always told Rhoda to bring her friends out here, but she never would do it,” the woman declared heartily. “Come inside and see our trailer.”

“We really should be going,” Penny demurred. “I told our housekeeper I’d be right back.”

“It will only take a minute,” Mrs. Breen urged. “I want you to meet my husband—and there’s Ted.”

The woman had caught a glimpse of a tall young man as he moved hastily around the back side of the trailer.

“Oh, Ted!” she called shrilly. “Come here and meet Rhoda’s friends!”

“Don’t bother about it, Mrs. Breen,” Rhoda said in embarrassment. “Please.”

“Nonsense!” the woman replied, and called again. “Ted! Come here, I say!”

With obvious reluctance, the young man approached the automobile. He was tall and slim with many of Rhoda’s facial features. Penny felt certain that she had seen him before, yet for a minute she could not think where.

“How are you?” the young man responded briefly as he was presented to the two girls.

“Ted found a little work to do today,” Mrs. Breen resumed proudly. “Just a few minutes ago he brought home a nice plump chicken. We’re having it for dinner!”

Ted gazed over the woman’s head, straight at his sister. Seeing the look which passed between them, Penny suddenly knew where she had seen the young man. Mrs. Breen’s remark had given her the required clue. Unquestionably, Ted Wiegand was the one who had stolen the chicken from the old stonecutter!

The discovery that Rhoda’s brother had stolen food was disconcerting to Penny. Saying good-bye to Mrs. Breen, she prepared to drive away from the trailer camp.

“Oh, you can’t go so soon,” the woman protested. “You must stay for dinner. We’re having chicken and there’s plenty for everybody!”

“Really we can’t remain,” Penny declined. “Louise and I both are expected at home.”

“You’re just afraid you’ll put me to a little trouble,” Mrs. Breen laughed, swinging open the car door and tugging at Penny’s hand. “You have to stay.”

Taking a cue from their mother, the three young children surrounded the girls, fairly forcing them toward the trailer. Ted immediately started in the opposite direction.

“You come back here, Ted Wiegand!” Mrs. Breen called in a loud voice.

“I don’t want any dinner, Mom.”

“I know better,” Mrs. Breen contradicted cheerfully. “You’re just bashful because we’re having two pretty girls visit us. You stay and eat your victuals like you always do, or I’ll box your ears.”

“Okay,” Ted agreed, glancing at Rhoda again. “It’s no use arguing with you, Mom.”

Neither Penny nor Louise wished to remain for dinner, yet they knew of no way to avoid it without offending Mrs. Breen. Briskly the woman herded them inside the trailer.

“It’s nice, isn’t it?” she asked proudly. “We have a little refrigerator and a good stove and a sink. We’re a bit crowded, but that only makes it more jolly.”

A man in shirt sleeves lay on one of the day beds, reading a newspaper.

“Meet my husband,” Mrs. Breen said as an afterthought. “Get up, Pop!” she ordered. “Don’t you have any manners?”

The man amiably swung his feet to the floor, grinning at Penny and Louise.

“I ain’t been very well lately,” he said, as if feeling that the situation required an explanation. “The Doc tells me to take it easy.”

“That was twenty years ago,” Mrs. Breen contributed, an edge to her voice. “Pop’s been resting ever since. But we get along.”

Rhoda and Ted, who had followed the others into the trailer, were acutely embarrassed by the remark. Penny hastily changed the subject to a less personal one by pretending to show an interest in a book which lay on the table.

“Oh, that belongs to Rhoda,” Mrs. Breen responded carelessly. “She brought it from the library. Ted and Rhoda always have their noses in a book. They’re my adopted children, you know.”

“Mr. and Mrs. Breen have been very kind to us,” Rhoda said quietly.

“Stuff and nonsense!” Mrs. Breen retorted. “You’ve more than earned your keep. Well, if you’ll excuse me now, I’ll dish up dinner.”

Penny and Louise wondered how so many persons could be fed in such a small space, especially as the dinette table accommodated only six. Mrs. Breen solved the problem by giving each of the three small children a plate of food and sending them outdoors.

“Now we can eat in peace,” she remarked, squeezing her ample body beneath the edge of the low, anchored table. “It’s a little crowded, but we can all get in here.”

“I’ll take my plate outside,” Ted offered.

“No, you stay right here,” Mrs. Breen reproved. “I never did see such a bashful boy! Isn’t he the limit?”

Having arranged everything to her satisfaction, she began to dish up generous helpings of chicken and potato. The food had an appetizing odor and looked well cooked, but save for a pot of tea, there was nothing else.

“We’re having quite a banquet tonight,” Pop Breen remarked appreciatively. “I’ll take a drumstick, Ma, if there ain’t no one else wantin’ it.”

“You’ll take what you get,” his wife retorted, slapping the drumstick onto Penny’s plate.

Louise and Penny made a pretense of eating, finding the food much better than they had expected. Neither Ted nor Rhoda seemed hungry, and Mrs. Breen immediately called attention to their lack of appetite.

“Why, Ted! What’s the matter you’re not eating? Are you sick?”

The boy shook his head and got to his feet.

“I’m not hungry, Mom,” he mumbled. “Excuse me, please. I have a date with a fellow at Riverview, and I have to hurry.”

Before Mrs. Breen could detain him, he left the trailer.

“I can’t understand that boy any more,” she observed with a sad shake of her head. “He hasn’t been himself lately.”

The younger members of the Breen family quite made up for Ted and Rhoda’s lack of appetite. Time and again they came to the table to have their plates refilled, until all that remained of the chicken was a few bones.

Penny and Louise felt quite certain that Rhoda realized what her brother had done and was deeply humiliated by his thievery. To spare the girl further embarrassment, they declared that they must leave. However, as they were presenting their excuses, there was a loud rap on the door of the trailer. Peering from the curtained window, Mrs. Breen immediately lost her jovial manner.

“He’s here again,” she whispered. “What are we going to tell him, Pop?”

“Just give him the old stall,” her husband suggested, undisturbed.

Reluctantly, Mrs. Breen went to open the door. Without waiting for an invitation, a well-dressed man of middle age entered the trailer. Penny immediately recognized him as Jay Franklin, who owned the Dorset Tourist Camp. “Good afternoon, Mrs. Breen,” he began, his manner falsely cheerful. “I suppose you know why I am here again?”

“About the rent?”

“Precisely.” Mr. Franklin consulted a small booklet. “You are behind one full month in your payments, as of course you must be aware. The amount totals eight dollars.”

“Pop, pay the gentleman,” Mrs. Breen commanded.

“Well, now, I ain’t got that much on me,” her husband rejoined, responding to his cue. “If you’ll drop around in a day or two, Mr. Franklin—”

“You’ve been stalling for weeks! Either pay or your electric power will be cut off!”

“Oh, Mr. Franklin,” pleaded Mrs. Breen, “you can’t do that to us. Why, with our refrigerator on the blink, the milk will sour. And I got three little children.”

The man regarded her with cold dislike.

“I am not interested in your personal problems, Mrs. Breen,” he said, delivering his ultimatum. “Either settle your bill in full by tomorrow morning, or move on!”

“What’ll we do?” Mrs. Breen murmured, gazing despairingly at her husband. “Where will we get the money?”

Penny stepped forward into Jay Franklin’s range of vision. Observing her for the first time, he politely doffed his hat, a courtesy he had not bestowed upon the Breens.

“Mr. Franklin, have you a cheque book?” she inquired.

“Yes, I have,” he responded with alacrity.

“Then I’ll write a cheque for the eight dollars if that will be satisfactory,” Penny offered. “The Breens are friends of mine.”

“That will settle the bill in full, Miss Parker.”

Whipping a fountain pen from his pocket, he offered it to her.

“Penny, we can’t allow you to assume our debts,” Rhoda protested. “Please don’t—”

“Now Rhoda, it’s only a loan to tide us over for a few days,” Mrs. Breen interposed. “Ted will get a job and then we’ll be able to pay it back.”

Penny wrote out the cheque, and cutting short the profuse thanks of the Breens, declared that she and Louise must return home at once.

“Driving into Riverview?” Mr. Franklin inquired. “My car is in the garage, and I’ll appreciate a lift to town.”

“We’ll be glad to take you, Mr. Franklin,” Penny responded, but without enthusiasm.

Enroute to Riverview he endeavored to make himself an agreeable conversationalist.

“So the Breens are friends of yours?” he remarked casually.

“Well, not exactly,” Penny corrected. “I met Rhoda at school and visited her for the first time today. I couldn’t help feeling sorry for the family.”

“They’re a no-good lot. The old man never works, and the boy either can’t or won’t get a job.”

“Do you have many such families, Mr. Franklin?”

“Oh, now and then. But I weed them out as fast as I can. One can’t be soft and manage a tourist camp, you know.”

Penny smiled, thinking that no person ever would accuse Mr. Franklin of being “soft.” He had the reputation of ruthless devotion to his own interests. Changing the subject, she remarked that Mrs. Marborough had returned to the city to take up residence at Rose Acres.

“Is that so?” Mr. Franklin inquired, showing interest in the information. “Will she recondition the house?”

Penny replied that she had no knowledge of the widow’s future plans.

“No doubt Mrs. Marborough has returned to sell the property,” Mr. Franklin said musingly. “I should like to buy that place if it goes for a fair price. I could make money by remodeling it into a tourist home.”

“It would be a pity to turn such a lovely place into a roadside hotel,” Louise remarked disapprovingly. “Penny and I hope that someday it will be restored as it was in the old days.”

“There would be no profit in it as a residence,” Mr. Franklin returned. “The house is located on a main road though, and as a tourist hotel, should pay.”

Conversation languished, and a few minutes later, Penny dropped the man at his own home. Although she refrained from speaking of it to Louise, she neither liked nor trusted Jay Franklin. While it had been his right to eject the Breens from the tourist camp for non-payment of rent, she felt that he could have afforded to be more generous. She did not regret the impulse which had caused her to settle the debt even though it meant that she must deprive herself of a few luxuries.

After leaving Louise at the Sidell house, Penny drove on home. Entering the living room, she greeted her father who had arrived from the newspaper office only a moment before. A late edition of the Star lay on the table, and she glanced carelessly at it, inquiring: “What’s new, Dad?”

“Nothing worthy of mention,” Mr. Parker returned.

Sinking down on the davenport, Penny scanned the front page. Immediately her attention was drawn to a brief item which appeared in an inconspicuous bottom corner.

“Here’s something!” she exclaimed. “Why, how strange!”

“What is, Penny?”

“It says in this story that a big rock has been found on the farm of Carl Gleason! The stone bears writing thought to be of Elizabethan origin!”

“Let me see that paper,” Mr. Parker said, striding across the room. “I didn’t know any such story was used.”

With obvious displeasure, the editor read the brief item which Penny indicated. Only twenty lines in length, it stated that a stone bearing both Elizabethan and Indian carving had been found on the nearby farm.

“I don’t know how this item got past City Editor DeWitt,” Mr. Parker declared. “It has all the earmarks of a hoax! You didn’t by chance write it, Penny?”

“I certainly did not.”

“It reads a little like a Jerry Livingston story,” Mr. Parker said, glancing at the item a second time.

Going to a telephone he called first the Star office and then the home of the reporter, Jerry Livingston. After talking with the young man several minutes, he finally hung up the receiver.

“What did he say?” Penny asked curiously.

“Jerry wrote the story, and says it came from a reliable source. He’s coming over here to talk to me about it.”

Within ten minutes the reporter arrived at the Parker home. Penny loitered in the living room to hear the conversation. Jerry long had been a particular friend of hers and she hoped that her father would not reprimand him for any mistake he might have made.

“Have a chair,” Mr. Parker greeted the young man cordially. “Now tell me where you got hold of that story.”

“Straight from the farmer, Carl Gleason,” Jerry responded. “The stone was dug up on his farm early this morning.”

“Did you see it yourself?”

“Not yet. It was hauled to the Museum of Natural Science. Thought I’d drop around there on my way home and look it over.”

“I wish you would,” requested the editor. “While the stone may be an authentic one, I have a deep suspicion someone is trying to pull a fast trick.”

“I’m sorry if I’ve made a boner, Chief.”

“Oh, I’m not blaming you,” Mr. Parker assured him. “If the story is a fake, it was up to DeWitt to question it at the desk. Better look at the rock though, before you write any more about it.”

As Jerry arose to leave, Penny jumped up from her own chair.

“I’d like to see that stone too!” she declared. “Jerry, do you mind if I go along with you?”

“Glad to have you,” he said heartily.

Before Penny could get her hat and coat, Mrs. Maud Weems, the Parker housekeeper, appeared in the doorway to announce dinner. She was a stout, pleasant woman of middle-age and had looked after Penny since Mrs. Parker’s death many years before.

“Penny, where are you going now?” she asked, her voice disclosing mild disapproval.

“Only over to the museum.”

“You’ve not had your dinner.”

“Oh, yes, I have,” Penny laughed. “I dined on chicken at the Dorset Tourist Camp. I’ll be home in an hour or so.”

Jerking coat and hat from the hall closet, she fled from the house before Mrs. Weems could offer further objections. Jerry made a more ceremonious departure, joining Penny on the front porch.

At the curb stood the reporter’s mud-splattered coupe. The interior was only slightly less dirty, and before getting in, Penny industriously brushed off the seat.

“Tell me all about this interesting stone which was found at the Gleason farm,” she commanded, as the car started down the street.

“Nothing to tell except what was in the paper,” Jerry shrugged. “The rock has some writing on it, supposedly similar to early Elizabethan script. And there are a few Indian characters.”

“How could such a stone turn up at Riverview?”

“Carl Gleason found it while he was plowing a field. Apparently, it had been in the ground for many years.”

“I should think so if it bears Elizabethan writing!” Penny laughed. “Why, that would date it practically in Shakespeare’s time!”

“It’s written in the style used by the earliest settlers of this country,” Jerry said defensively. “You know, before we had radios and automobiles and things, this land of ours was occupied by Indians.”

“Do tell!” Penny teased.

“The natives camped all along the river, and there may have been an early English settlement here. So it’s perfectly possible that such a stone could be found.”

“Anyway, I am curious to see it,” Penny replied.

The car drew up before a large stone building with Doric columns. Climbing a long series of steps to the front door, Penny and Jerry entered the museum through a turnstile.

“I want to see the curator, Mr. Kaleman,” the reporter remarked, turning toward a private office near the entrance. “I’ll be with you in a minute.”

While waiting, Penny wandered slowly about, inspecting the various display cases. She was admiring the huge skeleton of a dinosaur when Jerry returned, followed by an elderly man who wore spectacles. The reporter introduced the curator, who began to talk enthusiastically of the ancient stone which had been delivered to the museum that afternoon.

“I shall be very glad to show it to you,” he said, leading the way down a long corridor. “For the present, pending investigation, we have it stored in the basement.”

“What’s the verdict?” Jerry inquired. “Do museum authorities consider the writing authentic?”

“I should not wish to be quoted,” Mr. Kaleman prefaced his little speech. “However, an initial inspection has led us to believe that the stone bears ancient writings. You understand that it will take exhaustive study before the museum would venture to state this as a fact.”

“The stone couldn’t have been faked?” Penny asked thoughtfully.

“Always that is a possibility,” Mr. Kaleman acknowledged as he unlocked the door of a basement room. “However, the stone has weathered evenly, it appears to have been buried many years, and there are other signs which point to the authenticity of the writing.”

The curator switched on an electric light which disclosed a room cluttered with miscellaneous objects. There were empty mummy cases, boxes of excelsior, and various stuffed animals. At the rear of the room was a large rust colored stone which might have weighed a quarter of a ton.

“Here it is,” Mr. Kaleman declared, giving the rock an affectionate pat. “Notice the uniform coloring throughout. And note the lettering chiseled on the surface. You will see that the grooves do not differ appreciably from the remainder of the stone as would be the case if the lettering were of recent date. It is my belief—don’t quote me, of course—that this writing may open a new and fascinating page of history.”

Penny bent to inspect the crude writing. “‘Here laeth Ananias’” she read slowly aloud. “Why, that might be a joke! Wasn’t Ananias a dreadful prevaricator?”

“Ananias was a common name in the early days,” Mr. Kaleman said, displeased by the remark. “Now on the underside of this stone which you cannot see, there appears part of a quaint message which begins: ‘Soon after you goe for Englande we came hither.’”

“What does it mean?” questioned Jerry.

“This is only my theory, you understand. I believe the message may have been written by an early settler and left for someone who had gone to England but expected to return. The writing breaks off, suggesting that it may have been continued on another stone.”

“In that case, similar rocks may be found near here,” Jerry said thoughtfully.

“It is an interesting possibility. On the underside, this stone also contains a number of Indian characters, no doubt added at a later date. So far we have not been able to decipher them.”

“Just why does the stone have historical value?” Penny interposed.

“Because there never was any proof that English colonists settled in this part of the state,” Mr. Kaleman explained. “If we could prove such were the case, our contribution to history would be a vital one.”

Penny and Jerry asked many other questions, and finally left the museum. Both had been impressed not only with the huge stone but by the curator’s sincere manner.

“Mr. Kaleman certainly believes the writing is genuine,” Penny declared thoughtfully. “All the same, anyone knows a carved rock can be made to look very ancient. And that name Ananias makes me wonder.”

“The Chief may be right about it being a fake,” Jerry returned. “But if it is, who planted the stone on Gleason’s farm? And who would go to so much unnecessary work just to play a joke?”

Frowning, the reporter started to cross the street just as an automobile bearing Texas license plates went past, close to the curb. As Jerry leaped backwards to safety, the automobile halted. Two men occupied the front seat, and the driver, a well-dressed man of fifty, leaned from the window.

“Excuse me, sir,” he said, addressing Jerry, “we’re trying to locate a boy named Ted Wiegand. He and his sister may be living with a family by the name of Breen. Could you tell me how to find them?”

“Sorry, but I can’t,” Jerry answered. “I never heard either of the names.”

“Why, I know both Ted and Rhoda Wiegand,” Penny interposed quickly. “They’re living at the Dorset Tourist Camp.”

“How do we get there?” the driver of the Texas car inquired.

Jerry provided the requested information. Thanking him, the stranger and his companion drove on down the street.

“I wonder who they can be?” Penny speculated, staring after the car. “And why did they come all the way from Texas to see Rhoda and Ted?”

“Friends of yours?” Jerry asked carelessly.

“I like Rhoda very much. Ted seems to be a rather questionable character. I wonder—”

“You wonder what?” the reporter prompted, helping Penny into the parked automobile.

“It just came to me, Jerry!” she answered gravely. “Those men may be officers from Texas sent here to arrest Ted for something he’s done! I never meant to set them on his trail, but I may be responsible for his arrest!”

Jerry smiled broadly as he edged the car from its parking space by the curb.

“You certainly have a vivid imagination, Penny,” he accused. “Those two men didn’t look like plain-clothes men to me. Anyway, if Ted Wiegand had committed an illegal act, wouldn’t it be your duty to turn him over to the authorities?”

“I suppose so,” Penny admitted unwillingly. “Ted stole one of Truman Crocker’s chickens today. It was a dreadful thing to do, but in a way you couldn’t blame him too much. I’m sure the Breens needed food.”

“Stealing is stealing. I don’t know the lad, but if a fellow is crooked in small things, he’s usually dishonest otherwise as well. Speaking of Truman Crocker, he was the man who hauled the big rock to the museum.”

“Was he?” Penny inquired, not particularly interested in the information. “I understand he does a great deal of rock hauling around Riverview. A queer fellow.”

Becoming absorbed in her own thoughts, Penny had little to say until the car drew up in front of the Parker home.

“Won’t you come in?” she invited Jerry as she alighted.

“Can’t tonight,” he declined regretfully. “I have a date at a bowling alley.”

Mr. Parker had been called downtown to attend a meeting, Penny discovered upon entering the house. Unable to tell him of her trip to the museum, she tried to interest Mrs. Weems in the story. However, the housekeeper, who was eager to start for a moving-picture theatre, soon cut her short.

“Excuse me, Penny, but I really must be leaving or I’ll be late,” she apologized, putting on her hat.

“I thought you were interested in mystery, Mrs. Weems.”

“Mystery, yes,” smiled the housekeeper. “To tell you the truth, though, I can’t become very excited over an old stone, no matter what’s written on it.”

After Mrs. Weems had gone, Penny was left alone in the big house. She sat down to read a book but soon laid it aside. To pass the time, she thought she would make a batch of fudge. But, no sooner had she mixed the sugar and chocolate together than it seemed like a useless occupation, so she set aside the pan for Mrs. Weems to finish upon her return from the movie.

“I know what I’ll do!” she thought suddenly. “I wonder why I didn’t think of it sooner?”

Hastening to the telephone she called her chum, Louise, asking her to come over at once.

“What’s up?” the other inquired curiously.

“We’re going to carry out a philanthropic enterprise, Lou! I’ll tell you about it when you get here!”

“One of these days you’ll choke on some of those big words,” Louise grumbled. “All right, I’ll come.”

Fifteen minutes later she arrived at the Parker home to find Penny, garbed in an apron, working industriously in the kitchen.

“Say, what is this?” Louise demanded suspiciously. “If you tricked me into helping you with the dishes, I’m going straight home!”

“Oh, relax,” Penny laughed. “The dishes were done hours ago. We’re going to help out the Old Wishing Well.”

“I wish you would explain what you mean.”

“It’s this way, Lou. The Breens are as poor as church mice, and they need food. At the Marborough place this afternoon Rhoda made a wish—that her family would have more to eat. Well, it’s up to us to make that wish come true.”

“You’re preparing a basket of food to take out to the camp?”

“That’s the general idea. We can leave it on the doorstep of the trailer and slip away without revealing our identity.”

“Why, your idea is a splendid one!” Louise suddenly approved. “Of course Mrs. Weems said it would be all right to fix the basket of food?”

“Oh, she won’t mind. I know she would want me to do it if she were here.”

Swinging open the porcelain door of the ice box, Penny peered into the illuminated shelves. The refrigerator was unusually well stocked, for Mrs. Weems had baked that day in anticipation of week-end appetites. Without hesitation, Penny handed out a meat loaf, a plum pudding, bunches of radishes, scrubbed carrots, celery, and a dozen fresh eggs.

“Dash down to the basement and get some canned goods from the supply shelf,” she instructed Louise briskly. “We ought to have jelly too, and a sample of Mrs. Weems’ strawberry preserves.”

“You do the dashing, if you don’t mind,” her chum demurred. “I prefer not to become too deeply involved in this affair.”

“Oh, Mrs. Weems won’t care—not a bit,” Penny returned as she started for the basement. “She’s the most charitable person in the world.”

In a minute she was back, her arms laden with heavy canned goods. Finding a market basket in the garage, the girls packed the food, wrapping perishables carefully in waxed paper.

“There! We can’t crowd another thing into the basket,” Penny declared at last.

“The ice-box is as bare as Mother Hubbard’s cupboard,” Louise rejoined. “What will the Parker family eat tomorrow?”

“Oh, Mrs. Weems can buy more. She’ll be a good sport about it, I know.”

With no misgivings, Penny carried the heavy basket to the garage and loaded it into the car. Discovering that the gasoline gauge registered low, she skillfully siphoned an extra two gallons from her father’s car, and then announced that she was ready to go.

“Don’t you ever patronize a filling station?” Louise inquired as her chum headed the automobile down the street.

“Oh, now and then,” Penny grinned. “After that cheque I wrote for the Breens’ rent, I’m feeling rather poor. Dad is much better able to buy gasoline than I, and he won’t begrudge me a couple of gallons.”

“You certainly have your family well trained,” Louise sighed. “I wish I knew how you get by with it.”

The car toured through Riverview and presently arrived at the entrance of the Dorset Tourist Camp. An attendant stopped the girls, but allowed them to drive on when he learned that they did not wish to make reservations for a cabin. Penny drew up not far from where the Breen trailer was parked.

“A light is still burning there,” Louise observed. “We’ll have to be careful if we don’t want to be seen.”

As Penny lifted the heavy basket from the rear compartment of the automobile, she noticed another car standing not far away. It looked somewhat familiar and in studying it more intently she noted the license plate.

“Why, it’s that same Texas car!” she exclaimed. “Those men must still be here.”

“What car? What men?”

“Oh, this evening two strangers inquired the way to this tourist camp,” Penny explained briefly. “They said they were looking for Ted Wiegand.”

“Friends of his?”

“I don’t know who they were or what they wanted. It struck me as odd though, that they would come from such a long distance.”

“Whoever they are, they must be at the trailer now,” Louise said after a moment. “Should we leave the basket on the doorstep or wait until they’ve gone?”

“We can’t very well wait, Lou. They might decide to stay half the night.”

Carrying the basket between them, the girls moved noiselessly toward the trailer. Blinds had not been drawn and they could see Mr. and Mrs. Breen, Rhoda, and the two men seated at the table carrying on an animated discussion.

“I wish I knew why those Texas fellows came here,” Penny remarked thoughtfully. “If we wanted to find out—”

“I’ll not listen at any window!” Louise cut her short.

“I was merely thinking we could. Of course, I never would do such an ill-bred thing.”

“I’m sure you won’t,” Louise replied with emphasis. “For a very good reason too! I shall take you away before temptation sways you.”

Depositing the basket of food on the trailer doorstep, she forcibly pulled Penny to the waiting car.

At school the next morning, both Penny and Louise eagerly awaited some indication from Rhoda Wiegand that the basket of food had been discovered by the Breen family. The girl had failed to appear at five minutes to nine, and they began to wonder if she intended to absent herself from classes.

“Oh, by the way, what did Mrs. Weems say about last night’s little episode?” Louise asked her chum curiously.

“Entirely too much,” Penny sighed. “She sent me three thousand words on the budget problems of a housekeeper! If you don’t mind, let’s allow the subject to rest in peace.”

It was time for the final school bell, and the two girls started toward the assembly room. Just then Rhoda, breathless from hurrying, came into the hallway. Her eyes sparkled and obviously, she was rather excited.

“Girls, something strange happened last night!” she greeted Penny and Louise. “You’ll never guess!”

“We couldn’t possibly,” Louise said soberly.

“Two baskets of food were left at the door of our trailer! It’s silly to say it, I know, but it seems as if my wish at the old well must have had something to do with it.”

“Did you say two baskets of food were left?” Louise questioned, gazing sideways at Penny.

“Yes, one came early in the evening. Then this morning when Mrs. Breen opened the door, she found still another. You don’t suppose any of the members of the Palette Club did it, do you? We shouldn’t like to accept charity—”

“I’ll ask the girls if you want me to,” Penny offered hastily. “If any of them did, nothing was said about it to me.”

“Maybe the old well granted your wish, Rhoda,” Louise added. “You know, folks say it has a reputation for doing good deeds.”

The ringing of the school bell brought the conversation to an abrupt end. However, as Louise and Penny went to their seats, the latter whispered:

“Who do you suppose left that second basket on the Breen doorstep?”

“Probably one of the other club members had the same idea you did,” Louise responded. “Anyway, the Breens will be well fed for a few days at least.”

At recess Penny made a point of questioning every member of the Palette Club. Not one of the girls would admit having carried the basket to the trailer park, but all were agreed that Rhoda should be invited to join the art organization. Without exception, they liked the girl after becoming acquainted with her.

“The mystery deepens,” Penny commented to Louise as they wandered, arm in arm, about the school yard. “If no one in the Palette Club prepared the basket, then who did do it?”

“I guess we’ll have to attribute it to the old wishing well after all,” Louise chuckled. “Let me see your ears, my pet.”

“What for? Don’t you think I ever wash them?”

“I merely want to see if they’ve grown since we were at the Marborough place. Why, goodness me, I believe they are larger!”

Before Penny could think of a suitable retort, Rhoda joined the girls. Curious to learn more of the two Texas men who had arrived in Riverview, they gave the newcomer every opportunity to speak of it. As she remained uncommunicative, Penny brought up the subject by mentioning that two strangers had asked her how they might locate the trailer family.

“Yes, they found us all right,” Rhoda replied briefly. “Mr. Coaten came to see Ted.”

“An old friend, I suppose,” Louise remarked.

“Not exactly. I can’t figure out just why he did come here.”

Rhoda frowned and lapsed into silence. Penny and Louise did not question her further, and a few minutes later recess ended.

The affairs of the Breen family concerned Penny only slightly. Although she kept wondering why Mr. Coaten and his companion were in Riverview, she gave far more thought to the stone which had been dug up on the Gleason farm. Directly after school she proposed to Louise that they drive into the country and interview the farmer.

“I don’t mind the trip,” her chum said, “but why are you so interested in an old rock?”

“Oh, Dad thinks the whole story may be a hoax. I’d like to learn the truth, if I can.”

Mindful that in the past Penny had brought the Riverview Star many an important “scoop,” Louise was very willing to accompany her on the trip. Four-thirty found the two girls at the Gleason farm in conversation with the old farmer.

“I’ve been pestered to death ever since that rock was found here,” he told them somewhat crossly. “There’s nothing new to tell. I was plowing in the south field back of the barn, when I turned it up. I didn’t pay much attention until Jay Franklin come along and said the writing on it might interest the museum folks. He gave me a couple of dollars, and paid to have old man Crocker haul it to town.”

“I didn’t know Jay Franklin had an interest in the stone,” Penny remarked. “You say he gave you two dollars for it?”

“That’s right,” the farmer nodded. “I was glad to have the rock hauled off the place.”

Satisfied that they could learn no more, Penny and Louise inspected the hole from which the stone had been removed, and then drove toward Riverview.

“Mr. Gleason seemed honest enough,” Penny commented thoughtfully. “If the rock was deliberately planted on his farm I don’t believe he had anything to do with it.”

“He isn’t sufficiently clever to plan and carry out an idea like that,” Louise added. “Maybe the writing on the rock is genuine.”

“The curator of the museum thinks it may be. All the same, I’ll stack Dad’s opinion against them all.”

The car approached the old Marborough place, and Penny deliberately slowed down. To the surprise of the girls, they observed two automobiles parked in front of the property.

“It looks as if Mrs. Marborough has guests today,” Penny commented. “Shall we stop and say hello?”

“Well, I don’t know,” Louise replied doubtfully as the car drew up at the edge of the road. “We’re not really acquainted with her, and with others there—”

“They’re leaving now,” Penny said, jerking her head to draw attention to a group of ladies coming down the walk toward the street.

The visitors all were known to the two girls as women prominent in Riverview club circles. Mrs. Buckmyer, a stout, pompous lady who led the procession, was speaking to the others in an agitated voice.

“In all my life I never was treated with less courtesy! Mrs. Marborough at least might have invited us into her house!”

“I always understood that she was a queer person,” contributed another, “but one naturally would expect better manners from a Marborough.”

“I shouldn’t object to her manners if only she would allow the Pilgrimage Committee the use of her house,” added a third member of the group. “What a pity that she refuses to consider opening it during the Festival Week.”

Still chattering indignantly, the women entered their separate cars and drove away.

“What did you make of that?” Louise asked in perplexity.

“Apparently Mrs. Marborough gave them the brush off,” Penny chuckled. “I know Mrs. Buckmyer heads the Pilgrimage Committee.”

“What’s that?”

“Haven’t you heard about it, Louise? A group of club women decided to raise money by conducting a tour of old houses. In this community there are a number of places which date back over a hundred years.”

“And people will pay money to see them?”

“That’s the general idea. Festival Week has been set for the twenty-sixth of this month. During a five-day period the various homes are open, gardens will be on display, and costume parties may be held at them.”

“There’s only one colonial house that I’d care about getting inside,” Louise said. “I should like to see the interior of Rose Acres.”

“Maybe we can do it now. Mrs. Marborough invited us to visit her again.”

“Yes, but did she really mean it?”

“Why not find out?” Penny laughed, swinging open the car door.

Entering the grounds, the girls saw that very little had been done to the property since their last visit. A half-hearted attempt had been made to rake one side of the lawn and an overgrown lilac bush had been mercilessly mutilated. Shutters on the house remained closed and the entire place had a gloomy, deserted appearance.

Penny rapped on the door. Evidently Mrs. Marborough had noted the approach of the two girls for she responded to their knock immediately.

“Good afternoon,” Penny began, “we were driving by and thought we would drop in to see you again.”

“How nice of you,” Mrs. Marborough smiled. “Look over the garden as much as you please.”

“The garden—” Louise faltered, gazing quickly at Penny.

“Or make wishes at the well,” Mrs. Marborough went on hastily. “Go anywhere you like, and I’ll join you as soon as I get a wrap.”

The door closed gently in their faces.

“Who wants to see a tangle of weeds?” Louise demanded in a whisper. “Why didn’t Mrs. Marborough invite us into the house?”

“Why indeed?” echoed Penny, frowning thoughtfully. “There can be but one reason! She has a dark secret which she is trying to hide from the world!”

“Hiding a secret, my eye!” laughed Louise. “Penny Parker, sometimes I think that every person in Riverview suggests mystery and intrigue to you!”

“Then you explain why Mrs. Marborough doesn’t invite us into her house!” Penny challenged her chum. “And why did she turn the members of the Pilgrimage Committee away?”

“Oh, probably the place isn’t fixed up the way she wants it yet.”

“That’s no reason. No, she has a different one than that, Lou, and I’m curious to learn what it is.”

“You’re always curious,” Louise teased, taking Penny by the arm. “Come along. Let’s get a drink at the well.”

While the girls were lowering the bucket into the bricked cavern, Mrs. Marborough joined them, a woolen shawl thrown over her head and shoulders.

“I’ve not had time to get much work done yet,” she apologized. “I really must hire a man to clean up the grounds.”

“Then you have decided to make your home here?” Louise inquired eagerly.

“For the present, I may. Much depends upon how a certain project turns out.”

Penny and Louise waited hopefully, but Mrs. Marborough said no more. Changing the subject, she inquired about Rhoda Wiegand and the other members of the Palette Club.

“I like young people,” she declared brightly. “Do tell your friends to come to Rose Acres whenever they wish.”

“A rather strange thing occurred yesterday,” Penny said suddenly. “Rhoda made a wish here at the well, and it came true.”

“What was the wish?” the old lady inquired with curiosity.

“That the people with whom she lives might have more food. Two baskets were left at the trailer camp. Louise and I were responsible for one of them, but we can’t account for the other.”

“Very interesting,” Mrs. Marborough commented. “In years past, a great many wishes which were made here, apparently came true. So I can’t say that I am surprised.”

“To what do you attribute it?” Louise asked quickly.

“Chance perhaps,” Mrs. Marborough smiled. “One cannot explain such things.”

A chill, penetrating wind blew from the direction of the river. Shivering, Louise drew her jacket collar closer about her neck, remarking rather pointedly that the weather was turning colder. Even then, Mrs. Marborough did not suggest that the girls enter the house. A moment later, however, she excused herself and went inside, leaving them alone in the garden.

“It does seem odd that she acts so secretive,” Louise commented. “I’m inclined to agree with members of the Pilgrimage Committee that her manners aren’t the best.”

“Perhaps you’ll finally decide that I am right!” Penny said triumphantly. “Take my word for it, there’s something inside the house she doesn’t want anyone to see!”

Louise started slowly toward the road, only to pause as her chum proposed that they walk to the river and call upon Truman Crocker, the stonecutter.

“You intend to tell him who stole his chicken?” Louise asked in surprise.

Penny shook her head. “No, I’ll let him discover it for himself. I want to talk to him about that big rock he hauled to the museum.”

Louise could not imagine what useful information her chum might expect to gain, but she obediently trailed Penny through the rear yard of Rose Acres, down a sloping path which led to the river.

“I hope you know the way,” she remarked dubiously as the going became more difficult, and they were forced to move slowly.

“Oh, we can’t miss the cabin. Crocker’s place is the only one near here,” Penny responded.

The trail was a narrow one, so infrequently used that bushes and vines had overgrown it in many places. Finally emerging on an open hillside, the girls were able to gaze down upon the winding river. Recent rains had swollen it to the very edges of the banks, and from a distance Truman Crocker’s shack appeared to be situated dangerously close to the water.

“Wouldn’t you think he would soon be flooded out?” Louise commented, pausing to catch her breath. “I shouldn’t care to live so near the river.”

“Oh, the water never comes much higher,” Penny rejoined. “A few years ago the city built some sort of river control system which takes care of the spill should there be any. Anyway, Crocker’s place wouldn’t represent much of a loss if it did wash away.”

The girls regained their breath, and then started down the slope. Penny, who was leading the way, did not pay particular attention to the rutty path. Suddenly catching her shoe in a small hole, she tripped and fell sideways.

“Ooh, my arm!” she squealed. “I struck it on a big rock!”

Louise helped Penny to her feet, brushing dirt from the girl’s skirt.

“You’ve ripped your stocking,” she said sympathetically.

“I guess I’m lucky it wasn’t my head,” Penny returned gazing ruefully at the tear. “Let’s sit down and rest a minute.”

Seating herself on the large smooth rock, she gingerly examined a bruised place on her elbow. Louise stood beside her, plucking burs from her chum’s sweater.

“I’m all right now,” Penny said a moment later, getting up. “Why, Lou! Do you see what I’ve been sitting on?”

“A rock, my pet.”

“A stone that looks exactly like the one at the museum!” Penny cried excitedly.

“All rocks are pretty much alike, aren’t they?”

“Certainly not,” Penny corrected. “There are any number of varieties. This one is quartz unless I’m mistaken and it does resemble the one at the museum.”

“Maybe you can find some writing on it,” Louise teased. “The rock only weighs two or three hundred pounds. Shall I lift it for you so you can see the under side?”

“Don’t bother,” Penny retorted, eagerly examining the stone. “I’ve already found it.”

“Found what?”

“The writing! I knew this stone looked like the one at the museum!”

Louise was certain that her chum merely pretended to have made such an important discovery. However, as Penny continued to examine the rock in an intent, absorbed way, she decided to see for herself.

“Why, it’s true!” she exclaimed incredulously. “There is writing on the stone!”

Carved letters, so dimmed by age and weathering processes that they scarcely remained legible, had been cut unevenly in the hard surface.

“‘Went hence vnto heaven 1599,’” Louise deciphered slowly. “Why, 1599 would date this stone almost before there were known settlers in the country!”

“Almost—but not quite,” replied Penny. “Historians believe there were other settlements before that date. Obviously, this is a burial stone similar to the one found on the Gleason farm.”

“If it’s such an old rock why was it never discovered before?”

“The stone may be a fake, but that’s not for us to try to figure out. We’ve made an important discovery and the museum is sure to be interested!”

“Don’t forget that this is on Mrs. Marborough’s property,” Louise reminded her chum. “We’ll have to tell her about it.”

Retracing their way to Rose Acres, the girls knocked on the door. Mrs. Marborough soon appeared, looking none too pleased by their unexpected return.

“What is it?” she asked, blocking the doorway so that the girls could not see beyond her into the living room.

Breathlessly, Penny told of finding the dated stone on the hillside.

“Did you know such a rock was there?” she asked eagerly.

“I’ve never seen any stone with writing on it,” Mrs. Marborough replied. “Goodness knows there are plenty of boulders on my property though.”

“Another stone similar to it was found yesterday on the Gleason farm,” Louise revealed. “Do come and see it, Mrs. Marborough.”

Before the widow could reply, the three were startled by heavy footsteps on the veranda. Turning, the girls saw that Jay Franklin had approached without being observed. Politely, he doffed his hat.

“Excuse me, I couldn’t help overhearing your conversation,” he said, bowing again to Mrs. Marborough. “You were saying something about a rock which bears writing?”

“We found it on the hillside near here,” Penny explained. “It has a date—1599.”

“Then it must be a mate to the stone discovered by Mr. Gleason!”

“I’m sure it is.”

“Will you take me to the spot where you found it?” Mr. Franklin requested. “I am tremendously interested.”

“Of course,” Penny agreed, but her voice lacked enthusiasm.

She glanced toward Louise, noticing that her chum did not look particularly elated either. Neither could have explained the feeling, but Jay Franklin’s arrival detracted from the pleasure of their discovery. Although ashamed of their suspicions, they were afraid that the man might try to take credit for finding the stone.

As if to confirm the thought of the two girls, Jay Franklin remarked that should the newly discovered stone prove similar to the one found at the Gleason farm, he would immediately have it hauled to the Riverview museum.

“Isn’t that for Mrs. Marborough to decide?” Penny asked dryly. “The rock is on her land, you know.”

“To be sure, to be sure,” Mr. Franklin nodded, brushing aside the matter of ownership as if it were of slight consequence.

Mrs. Marborough had gone into the house for a coat. Reappearing, she followed Mr. Franklin and the two girls down the trail where the huge stone lay.

“Did you ever notice this rock?” Penny questioned the mistress of Rose Acres.

“Never,” she replied, “but then I doubt that I ever walked in this particular locality before.”

Jay Franklin stooped to examine the carving, excitedly declaring that it was similar to the marking of the Gleason stone.

“And here are other characters!” he exclaimed, fingering well-weathered grooves which had escaped Penny’s attention. “Indian picture writing!”

“How do you account for two types of carving on the same stone?” Louise inquired skeptically.

“The Indian characters may have been added at a later date,” Mr. Franklin answered. “For all we know, this rock may be one of the most valuable relics ever found in our state! From the historical standpoint, of course. The stone has no commercial value.”

“I imagine the museum will want it,” Penny said thoughtfully.

“Exactly what I was thinking.” Mr. Franklin turned toward Mrs. Marborough to ask: “You would not object to the museum having this stone?”

“Why, no,” she replied. “It has no value to me.”

“Then with your permission, I’ll arrange to have it hauled to Riverview without delay. I’ll buy the stone from you.”

“The museum is entirely welcome to it.”

“There is a possibility that the museum will refuse the stone. In that event you would have the expense of hauling it away again. By purchasing it outright, I can relieve you of all responsibility.”

Giving Mrs. Marborough no opportunity to protest, the real estate man forced a crisp two dollar bill into her unwilling hand.

“There,” he said jovially, “now I am the owner of the stone. I’ll just run down to Truman Crocker’s place and ask him to do the hauling for me.”

The wind was cold, and after Mr. Franklin had gone, Mrs. Marborough went quickly to the house, leaving the girls to await his return.

“I knew something like this would happen,” Penny declared in annoyance. “Now it’s Mr. Franklin’s stone, and the next thing we know, he’ll claim that he discovered it too!”

Louise nodded gloomily, replying that only bad luck had brought the real estate agent to Rose Acres that particular afternoon.

“I have a sneaking notion he came here to buy Mrs. Marborough’s house,” Penny said musingly. “He thinks it would make a good tourist place!”

For half an hour the girls waited patiently. Neither Jay Franklin nor Truman Crocker appeared, so at last they decided it was a waste of time to remain longer. Arriving at home, shortly before the dinner hour, Penny found her father there ahead of her. To her surprise she learned that he already knew of the stone which had been discovered at Rose Acres.

“Information certainly travels fast,” she commented. “I suppose Jay Franklin must have peddled the story the minute he reached town.”

“Yes, he called at the Star office to report he had found a stone similar to the one unearthed at the Gleason farm,” Mr. Parker nodded.

“He found it!” Penny cried indignantly. “Oh, I knew that old publicity seeker would steal all the credit! Louise and I discovered that rock, and I hope you say so in the Star.”

“Franklin let it drop that he will offer the stone to the museum for five hundred dollars.”

“Well, of all the cheap tricks!” Penny exclaimed, her indignation mounting. “He bought that rock for two dollars, pretending he meant to give it to the museum. Just wait until Mrs. Marborough hears about it!”

“Suppose you tell me the facts,” Mr. Parker invited.

Penny obligingly revealed how she had found the rock by stumbling against it in descending a steep path to the river. Upon learning of the transaction which Jay Franklin had concluded with Mrs. Marborough, Mr. Parker smiled ruefully.

“Franklin always did have a special talent for making money the easy way,” he declared. “I’ll be sorry to see him cheat the museum.”

“Dad, you don’t think Mr. Kaleman will be foolish enough to pay money for that rock?” Penny asked in dismay.

“I am afraid he may. He seems convinced that the Gleason stone is a genuine specimen.”

“You still believe the writing to be faked?”

“I do,” Mr. Parker responded. “I’ll stake my reputation upon it! I said as much to Jay Franklin today and he rather pointedly hinted that he would appreciate having me keep my theories entirely to myself.”

“I guess he doesn’t understand you very well,” Penny smiled. “Now you’ll be more determined than ever to expose the hoax—if hoax it is.”

Mr. Franklin’s action thoroughly annoyed her for she felt that he had deliberately deceived Mrs. Marborough. Wishing to tell Louise Sidell what he had done, she immediately telephoned her chum.

“I’ve learned something you’ll want to hear,” she disclosed. “No, I can’t tell you over the ’phone. Meet me directly after dinner. We might go for a sail on the river.”

The previous summer Mr. Parker had purchased a small sailboat which he kept at a summer camp on the river. Occasionally he enjoyed an outing, but work occupied so much of his time that his daughter and her friends derived far more enjoyment from the craft than he did.

Louise accepted the invitation with alacrity, and later that evening, driving to the river with Penny, listened indignantly to a colored account of how Jay Franklin would profit at the widow’s expense. She agreed with her chum that he had acted dishonestly in trying to sell the stone.

“Perhaps Mrs. Marborough can claim ownership even now,” she suggested thoughtfully.

“Not without a lawsuit,” Penny offered as her opinion. “She sold the rock to Mr. Franklin for two dollars. Remember his final words: ‘Now I am the owner of the stone.’ Oh, he intended to trick her even then!”

The car turned into a private dirt road and soon halted beside a cabin of logs. A cool breeze came from the river, but the girls were prepared for it, having worn warm slack suits.

“It’s a grand night to sail,” Penny declared, leading the way to the boathouse. “We should get as far as the Marborough place if the breeze holds.”

Launching the dinghy, Louise raised the sail while her chum took charge of the tiller. As the canvas filled, the boat heeled slightly and began to pick up speed.

“Now use discretion,” Louise warned as the dinghy tilted farther and farther sideways. “It’s all very well to sail on the bias, but I prefer not to get a ducking!”

During the trip up the river the girls were kept too busy to enjoy the beauty of the night. However, as the boat approached Truman Crocker’s shack, the breeze suddenly died, barely providing steerage way. Holding the tiller by the pressure of her knee, Penny slumped into a half-reclining position.

“Want me to steer for awhile?” Louise inquired.

“Not until we turn and start for home. We’ll have the current with us then, which will help, even if the breeze has died.”

Curiously, Penny gazed toward Truman Crocker’s cabin which was entirely dark. High on the hillside stood the old Marborough mansion and there, too, no lights showed.

“Everyone seems to have gone to bed,” she remarked. “It must be late.”

Louise held her watch so that she could read the figures in the bright moonlight and observed that it was only a quarter past ten.

“Anyway, we should be starting for home,” Penny said. “Coming about!”

Louise prepared to lower her head as the boom swung over, but to her surprise the maneuver was not carried through. Instead of turning, the dinghy kept steadily on its course.