The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Airlords of Han, by Philip Francis Nowlan This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Airlords of Han Author: Philip Francis Nowlan Illustrator: Frank R. Paul Release Date: May 11, 2008 [EBook #25438] [Most recently updated: August 27, 2008] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE AIRLORDS OF HAN *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Stephen Blundell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from Amazing Stories Fact and Science Fiction May 1962 and was first published in Amazing Stories March 1929. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed. Minor spelling and typographical errors have been corrected without note. A table of contents has been provided below:

Illustrated by FRANK R. PAUL

Copyright, 1927, by E. P. Co., Inc.

In a previous record of my adventures in the early part of the Second War of Independence I explained how I, Anthony Rogers, was overcome by radioactive gases in an abandoned mine near Scranton in the year 1927, where I existed in a state of suspended animation for nearly five hundred years; and awakened to find that the America I knew had been crushed under the cruel tyranny of the Airlords of Han, fierce Mongolians, who, as scientists now contend, had in their blood a taint not of this earth, and who with science and resources far in advance of those of a United States, economically prostrate at the end of a long series of wars with a Bolshevik Europe, in the year 2270 A.D., had swept down from the skies in their great airships that rode "repeller rays" as a ball rides the stream of a fountain, and with their terrible "disintegrator rays" had destroyed more than four-fifths of the American race, and driven the other fifth to cover in the vast forests which grew up over the remains of the once mighty civilization of the United States.

I explained the part I played in the fall of the year 2419, when the rugged Americans, with science secretly developed to terrific efficiency in their forest fastness, turned fiercely and assumed the aggressive against a now effete Han population, which for generations had shut itself up in the fifteen great Mongolian cities of America, having abandoned cultivation of the soil and the operation of mines; for these Hans produced all they needed in the way of food, clothing, shelter and machinery through electrono-synthetic processes.

I explained how I was adopted into the Wyoming Gang, or clan, descendants of the original populations of Wilkes-Barre, Scranton and the Wyoming Valley in Pennsylvania; how quite by accident I stumbled upon a method of destroying Han aircraft by shooting explosive rockets, not directly at the heavily armored ships, but at the repeller ray columns, which automatically drew the rockets upward where they exploded in the generators of the aircraft; how the Wyomings threw the first thrill of terror into the Airlords by bringing an entire squadron crashing to earth; how a handful of us in a rocketship successfully raided the Han city of Nu-Yok; and how by the application of military principles I remembered from the First World War, I was able to lead the Wyomings to victory over the Sinsings, a Hudson River tribe which had formed a traitorous alliance with the hereditary enemies and oppressors of the White Race in America.

By the Spring of 2420 A.D., a short six months after these events, the positions of the Yellow and the White Races in America had been reversed. The hunted were now the hunters. The Hans desperately were increasing the defenses of their fifteen cities, around each of which the American Gangs had drawn a widely deployed line of long-gunners; while nervous air convoys, closely bunched behind their protective screen of disintegrator beams, kept up sporadic and costly systems of transportation between the cities.

During this period our own campaign against the Hans of Nu-Yok was fairly typical of the development of the war throughout the country. Our force was composed of contingents from most of the Gangs of Pennsylvania, Jersey and New England. We encircled the city on a wide radius, our line running roughly from Staten Island to the forested site of the ancient city of Elizabeth, to First and Second Mountains just west of the ruins of Newark, Bloomfield and Montclair, thence Northeasterly across the Hudson, and down to the Sound. On Long Island our line was pushed forward to the first slopes of the hills.

We had no more than four long-gunners to the square mile in our first line, but each of these was equal to a battery of heavy artillery such as I had known in the First World War. And when their fire was first concentrated on the Han city, they blew its outer walls and roof levels into a chaotic mass of wreckage before the nervous Yellow engineers could turn on the ring of generators which surrounded the city with a vertical film of disintegrator rays. Our explosive rockets could not penetrate this film, for it disintegrated them instantly and harmlessly, as it did all other material substance with the sole exception of "inertron," that synthetic element developed by the Americans from the sub-electronic and ultronic orders.

The continuous operation of the disintegrators destroyed the air and maintained a constant vacuum wherever they played, into which the surrounding air continuously rushed, naturally creating atmospheric disturbances after a time, which resulted in a local storm. This, however, ceased after a number of hours, when the flow of air toward the city became steady.

The Hans suffered severely from atmospheric conditions inside their city at first, but later rearranged their disintegrator ring in a system of overlapping films that left diagonal openings, through which the air rushed to them, and through which their ships emerged to scout our positions.

We shot down seven of their cruisers before they realized the folly of floating individually over our invisible line. Their beams traced paths of destruction like scars across the countryside, but caught less than half a dozen of our gunners all told, for it takes a lot of time to sweep every square foot of a square mile with a beam whose cross section is not more than twenty or twenty-five feet in diameter. Our gunners, completely concealed beneath the foliage of the forest, with weapons which did not reveal their position, as did the flashes and detonation of the Twentieth Century artillery, hit their repeller rays with comparative ease.

The "drop ships," which the Hans next sent out, were harder to handle. Rising to immense heights behind the city's disintegrator wall, these tiny, projectile-like craft slipped through the rifts in the cylinder of destruction, and then turning off their repeller rays, dropped at terrific speed until their small vanes were sufficient to support them as they volplaned in great circles, shooting back into the city defenses at a lower level.

The great speed of these craft made it almost impossible to register a direct hit against them with rocket guns, and they had no repeller rays at which we might shoot while they were over our lines.

But by the same token they were able to do little damage to us. So great was the speed of a drop ship, that the only way in which it could use a disintegrator ray was from a fixed generator in the nose of the structure, as it dropped in a straight line toward its target. But since they could not sight the widely deployed individual gunners in our line, their scouting was just as ineffective as our attempts were to shoot them down.

For more than a month the situation remained a deadlock, with the Hans locked up in their cities, while we mobilized gunners and supplies.

Had our stock of inertron been sufficiently great at this period, we could have ended the war quickly, with aircraft impervious to the "dis" ray. But the production of inertron is a painfully slow process, involving the building up of this weightless element from ultronic vibrations through the sub-electronic, electronic and atomic states into molecular form. Our laboratories had barely begun production on a quantity basis, for we had just learned how to protect them from Han air raids, and it would be many months more before the supply they had just started to manufacture would be finished. In the meantime we had enough for a few aircraft, for jumping belts and a small amount of armor.

We Wyomings possessed one swooper completely sheathed with inertron and counterweighted with ultron. The Altoonas and the Lycomings also had one apiece. But a shielded swooper, while impervious to the "dis" ray, was helpless against squadrons of Han aircraft, for the Hans developed a technique of playing their beams underneath the swooper in such fashion as to suck it down flutteringly into the vacuum so created, until they brought it finally, and more or less violently, to earth.

Ultimately the Hans broke our blockade to a certain extent, when they resumed traffic between their cities in great convoys, protected by squadrons of cruisers in vertical formation, playing a continuous cross-fire of disintegrator beams ahead of them and down on the sides in a most effective screen, so that it was very difficult for us to get a rocket through to the repeller rays.

But we lined the scar paths beneath their air routes for miles at a stretch with concealed gunners, some of whom would sooner or later register hits, and it was seldom that a convoy made the trip between Nu-Yok and Bos-Tan, Bah-Flo, Si-ka-ga or Ah-la-nah without losing several of its ships.

Hans who reached the ground alive were never taken prisoner. Not even the splendid discipline of the Americans could curb the wild hate developed through centuries of dastardly oppression, and the Hans were mercilessly slaughtered, when they did not save us the trouble by committing suicide.

Several times the Hans drove "air wedges" over our lines in this vertical or "cloud bank" formation, ploughing a scar path a mile or more wide through our positions. But at worst, to us, this did not mean the loss of more than a dozen men and girls, and generally their raids cost them one or more ships. They cut paths of destruction across the map, but they could not cover the entire area, and when they had ploughed out over our lines, there was nothing left for them to do but to turn around and plough back to Nu-Yok. Our lines closed up again after each raid, and we continued to take heavy toll from convoys and raiding fleets. Finally they abandoned these tactics.

So at the time of which I speak, the Spring of 2420 A.D., the Americans and the Hans were temporarily at pretty much of a deadlock. But the Hans were as desperate as we were sanguine, for we had time on our side.

It was at this period that we first learned of the Airlords' determination, a very unpopular one with their conscripted populations, to carry the fight to us on the ground. The time had passed when command of the air meant victory. We had no visible cities nor massed bodies of men for them to destroy, nothing but vast stretches of silent forests and hills, where our forces lurked, invisible from the air.

One of our Wyoming girls, on contact guard near Pocono, blundered into a hunting camp of the Bad Bloods, one of the renegade American Gangs, which occupied the Blue Mountain section North of Delaware Water Gap. We had not invited their cooperation in this campaign, for they were under some suspicion of having trafficked with the Hans in past years, but they had offered no objection to our passage through their territory in our advance on Nu-Yok.

Fortunately our contact guard had been able to leap into the upper branches of a tree without being discovered by the Bad Bloods, for their discipline was lax and their guard careless. She overheard enough of the conversation of their Bosses around the camp fire beneath her to indicate the general nature of the Han plans.

After several hours she was able to leap away unobserved through the topmost branches of the trees, and after putting several miles between herself and their camp, she ultrophoned a full report to her Contact Boss back in the Wyoming Valley. My own Ultrophone Field Boss picked up the message and brought the graph record of it to me at once.

Her report was likewise picked up by the Bosses of the various Gang units in our line, and we had called a council to discuss our plans by word of mouth.

We were gathered in a sheltered glade on the eastern slope of First Mountain on a balmy night in May. Far to the east, across the forested slopes of the lowlands, the flat stretches of open meadow and the rocky ridge that once had been Jersey City, the iridescent glow of Nu-Yok's protecting film of annihilation shot upward, gradually fading into a starry sky.

In the faint glow of our ultronolamps, I made out the great figure and rugged features of Boss Casaman, commander of the Mifflin unit, and the gray uniform of Boss Warn, who led the Sandsnipers of the Barnegat Beaches, and who had swooped over from his headquarters on Sandy Hook. By his side stood Boss Handan of the Winslows, a Gang from Central Jersee. In the group also were the leaders of the Altoonas, the Camerons, the Lycomings, Susquannas, Harshbargs, Hagersduns, Chesters, Reddings, Delawares, Elmirans, Kiugas, Hudsons and Connedigas.

Most of them were clad in forest-green uniforms that showed black at night, but each had some distinctive badge or item of uniform or equipment that distinguished his Gang.

Both the Mifflin and Altoona Bosses, for instance, wore heavy-looking boots with jointed knees. They came from sections that were not only mountainous, but rocky, where "leaping" involves many a slip and bruised limb, unless some protection of this sort is worn. But these boots were not as heavy as they looked, being counter-balanced somewhat with inertron.

The headgear of the Winslows was quite different from the close-fitting helmet of the Wyomings, being large and bushy-looking, for in the Winslow territory there were many stretches of nearly bare land, with occasional scrubby pines, and a Winslow caught in the open, on the approach of a Han airship, would twist himself into a motionless imitation of a scrubby plant, that passed very successfully for the real thing, when viewed from several thousand feet in the air.

The Susquannas had a unit that was equipped with inertron shields, that were of the same shape as those of the ancient Romans, but much larger, and capable of concealing their bearers from head to foot when they crouched slightly. These shields, of course, were colored forest green, and were irregularly shaded; they were balanced with inertron, so that their effective weight was only a few ounces. They were curious too, in that they had handles for both hands, and two small reservoir rocket-guns built into them as integral parts.

In going into action, the Susquannas crouched slightly, holding the shields before them with both hands, looking through a narrow vision slit, and working both rocket guns. The shields, however, were a great handicap in leaping, and in advancing through heavy forest growth.

The field unit of the Delawares was also heavily armored. It was one of the most efficient bodies of shock troops in our entire line. They carried circular shields, about three feet in diameter, with a vision slit and a small rocket gun. These shields were held at arm's length in the left hand on going into action. In the right hand was carried an ax-gun, an affair not unlike the battle-ax of the Middle Ages. It was about three feet long. The shaft consisted of a rocket gun, with an ax-blade near the muzzle, and a spike at the other end. It was a terrible weapon. Jointed leg-guards protected the ax-gunner below the rim of his shield, and a hemispherical helmet, the front section of which was of transparent ultron reaching down to the chin, completed his equipment.

The Susquannas also had a long-gun unit in the field.

One company of my Wyomings I had equipped with a weapon which I designed myself. It was a long-gun which I had adapted for bayonet tactics such as American troops used in the First World War, in the Twentieth Century. It was about the length of the ancient rifle, and was fitted with a short knife bayonet. The stock, however, was replaced by a narrow ax-blade and a spike. It had two hand-guards also. It was fired from the waist position.

In hand-to-hand work one lunged with the bayonet in a vicious, swinging up-thrust, following through with an up-thrust of the ax-blade as one rushed in on one's opponent, and then a down-thrust of the butt-spike, developing into a down-slice of the bayonet, and a final upward jerk of the bayonet at the throat and chin with a shortened grip on the barrel, which had been allowed to slide through the hands at the completion of the down-slice.

I almost regretted that we would not find ourselves opposed to the Delaware ax-men in this campaign, so curious was I to compare the efficiency of the two bodies.

But both the Delawares and my own men were elated at the news that the Hans intended to fight it out on the ground at last, and the prospect that we might in consequence come to close quarters with them.

Many of the Gang Bosses were dubious about our Wyoming policy of providing our fighters with no inertron armor as protection against the disintegrator ray of the Hans. Some of them even questioned the value of all weapons intended for hand-to-hand fighting.

As Warn, of the Sandsnipers put it: "You should be in a better position than anyone, Rogers, with your memories of the Twentieth Century, to appreciate that between the superdeadliness of the rocket gun and of the disintegrator ray there will never be any opportunity for hand-to-hand work. Long before the opposing forces could come to grips, one or the other will be wiped out."

But I only smiled, for I remembered how much of this same talk there was five centuries ago, and that it was even predicted in 1914 that no war could last more than six months.

That there would be hand-to-hand work before we were through, and in plenty, I was convinced, and so every able-bodied youth I could muster was enrolled in my infantry battalion and spent most of his time in vigorous bayonet practice. And for the same reason I had discarded the idea of armor. I felt it would be clumsy, and questioned its value. True, it was an absolute bar against the disintegrator ray, but of what use would that be if a Han ray found a crevice between overlapping plates, or if the ray was used to annihilate the very earth beneath the wearer's feet?

The only protective equipment that I thought was worth a whoop was a very peculiar device with which a contingent of five hundred Altoonas was supplied. They called it the "umbra-shield." It was a bell-shaped affair of inertron, counterweighted with ultron, about eight feet high. The gunner, who walked inside it, carried it easily with two shoulder straps. There were handles inside too, by which the gunner might more easily balance it when running, or lift it to clear any obstructions on the ground.

In the apex of the affair, above his head, was a small turret, containing an automatic rocket gun. The periscopic gun sight and the controls were on a level with the operator's eyes. In going into action he could, after taking up his position, simply stoop until the rim of the umbra-shield rested on the ground, or else slip off the shoulder straps, and stand there, quite safe from the disintegrator ray, and work his gun.

But again, I could not see what was to prevent the Hans from slicing underneath it, instead of directly at it, with their rays.

As I saw it, any American who was unfortunate enough to get in the direct path of a "dis" ray, was almost certain to "go out," unless he was locked up tight in a complete shell of inertron, as for instance, in an inertron swooper. It seemed to me better to concentrate all our efforts on tactics of attack, trusting to our ability to get the Hans before they got us.

I had one other main unit besides my bayonet battalion, a long-gun contingent composed entirely of girls, as were my scout units and most of my auxiliary contingents. These youngsters had been devoting themselves to target practice for months, and had developed a fine technique of range-finding and the various other tactics of Twentieth Century massed artillery, to which was added the scientific perfection of the rocket guns and an average mental alertness that would have put the artilleryman of the First World War to shame.

From the information our contact guard had obtained, it appeared that the Hans had developed a type of "groundship" completely protected by a disintegrator ray "canopy" that was operated from a short mast, and spread down around it as a cone.

These ships were merely adaptations of their airships, and were designed to travel but a few feet above the ground. Their repeller rays were relatively weak; just strong enough to lift them about ten or twelve feet from the surface. Hence they would draw but lightly upon the power broadcast from the city, and great numbers of them could be used. A special ray at the stern propelled them, and an extra-lift ray in the bow enabled them to nose up over ground obstacles. Their most formidable feature was the cone-shaped "canopy" of short-range disintegrator rays designed to spread down around them from a circular generator at the tip of a twenty-foot mast amidship. This would annihilate any projectile shot at it, for they naturally could not reach the ship without passing through the cone of rays.

It was instantly obvious that the "ground ships" would prove to be the "tanks" of the Twenty-fifth century, and with due allowance for the fact that they were protected with a sheathing of annihilating rays instead of with steel, that they would have about the same handicaps and advantages as tanks, except that since they would float lightly on short repeller rays, they could hardly resort to the destructive crushing tactics of the tanks of the First World War.

As soon as our first supplies of inertron-sheathed rockets came through, their invulnerability would be at an end, as indeed would be that of the Han cities themselves. But these projectiles were not yet out of the factories.

In the meantime, however, the groundships would be hard to handle. Each of them we understood would be equipped with a thin long-range "dis" ray, mounted in a turret at the base of the mast.

We had no information as to the probable tactics of the Hans in the use of these ships. One sure method of destroying them would be to bury mines in their path, too deep for the penetration of their protecting canopy, which would not, our engineers estimated, cut deeper than about three feet a second. But we couldn't ring Nu-Yok with a continuous mine on a radius of from five to fifteen or twenty miles. Nor could we be certain beforehand of the direction of their attack.

In the end, after several hours' discussion, we agreed on a flexible defense. Rather than risk many lives, we would withdraw before them, test their effectiveness and familiarize ourselves with the tactics they adopted. If possible, we would send engineers in behind them from the flanks, to lay mines in the probable path of their return, providing their first attack proved to be a raid and not an advance to consolidate new positions.

Boss Handan, of the Winslows, a giant of a man, a two-fisted fighter and a leader of great sagacity, had been selected by the council as our Boss pro tem, and having given the scatter signal to the council, he retired to our general headquarters, which we had established on Second Mountain a few miles in the rear of the fighting front in a deep ravine.

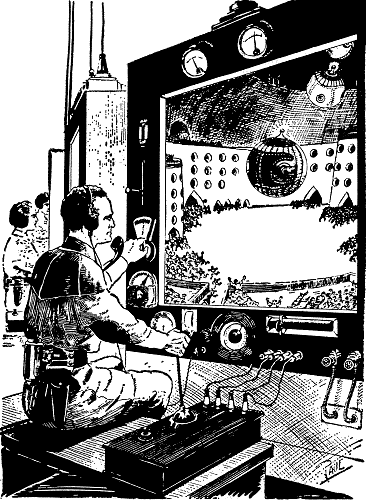

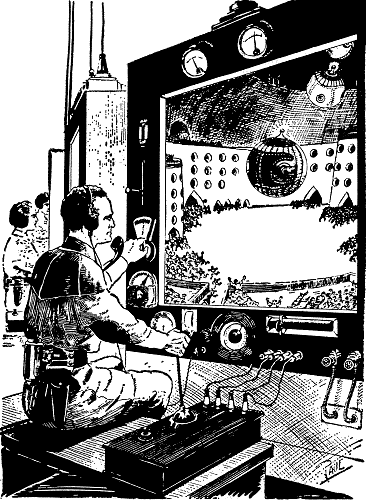

There, in quarters cut far below the surface, he would observe every detail of the battle on the wonderful system of viewplates our ultrono engineers had constructed through a series of relays from ultroscope observation posts and individual "cameramen."

Two hours before dawn our long distance scopemen reported a squadron of "ground ships" leaving the enemy's disintegrator wall, and heading rapidly somewhat to the south of us, toward the site of the ancient city of Newark. The ultroscopes could detect no canopy operation. This in itself was not significant, for they were penetrating hills in their lines of vision, most of them, which of course blurred their pictures to a slight extent. But by now we had a well-equipped electronoscope division, with instruments nearly equal to those of the Hans themselves; and these could detect no evidence of dis rays in operation.

Handan appreciated our opportunity instantly, for no sooner had the import of the message on the Bosses' channel become clear than we heard his personal command snapped out over the long-gunners' general channel.

Nine hundred and seventy long-gunners on the south and west sides of the city, concealed in the dark fastnesses of the forests and hillsides, leaped to their guns, switched on their dial lights, and flipped the little lever combinations on their pieces that automatically registered them on the predetermined position of map section HM-243-839, setting their magazines for twenty shots, and pressing their fire buttons.

For what seemed an interminable instant nothing happened.

Then several miles to the southeast, an entire section of the country literally blew up, in a fiery eruption that shot a mile into the air. The concussion, when it reached me, was terrific. The light was blinding.

And our scopemen reported the instant annihilation of the squadron.

What happened, of course, was this; the Hans knew nothing of our ability to see at night through our ultroscopes. Regarding itself as invisible in the darkness, and believing our instruments would pick up its location when its dis rays went into operation, the squadron made the fatal error of not turning on its canopies.

To say that consternation overwhelmed the Han high command would be putting it mildly. Despite their use of code and other protective expedients, we picked up enough of their messages to know that the incident badly demoralized them.

Their next attempt was made in daylight. I was aloft in my swooper at the time, hanging motionless about a mile up. Below, the groundships looked like a number of oval lozenges gliding across a map, each surrounded by a circular halo of luminescence that was its dis ray canopy.

They had nosed up over the spiny ridge of what once had been Jersey City, and were moving across the meadowlands. There were twenty of them.

Coming to the darker green that marked the forest on the "map" below me, they adopted a wedge formation, and playing their pencil rays ahead of them, they began to beam a path for themselves through the forest. In my ears sounded the ultrophone instructions of my executives to the long-gunners in the forest, and one by one I heard the girls report their rapid retirement with their guns and other inertron-lightened equipment. I located several of them with my scopes, with which I could, of course, focus through the leafy screen above them, and noted with satisfaction the unhurried speed of their movements.

On ploughed the Han wedge, while my girls separated before it and retired to the sides. With a rapidity much greater than that of the ships themselves, the beams penetrated deeper and deeper into the forest, playing continuously in the same direction, literally melting their way through, as a stream of hot water might melt its way through a snow bank.

Then a curious thing happened. One of the ships near one wing of the wedge must have passed over unusually soft ground, or perhaps some irregularity in the control of its canopy generator caused it to dig deeper into the earth ahead of it, for it gave a sudden downward lurch, and on coming up out of it, swerved a bit to one side, its offense beam slicing full into the ship echeloned to the left ahead of it. That ship, all but a few plates on one side, instantly vanished from sight. But the squadron could not stop. As soon as a ship stood still, its canopy ray playing continuously in one spot, the ground around it was annihilated to a continuously increasing depth. A couple of them tried it, but within a space of seconds, they had dug such deep holes around themselves that they had difficulty in climbing out. Their commanders, however, had the foresight to switch off their offense rays, and so damaged no more of their comrades.

I switched in with my ultrophone on Boss Handan's channel, intending to report my observation, but found that one of our swooper scouts, who, like myself, was hanging above the Hans, was ahead of me. Moreover, he was reporting a suddenly developed idea that resulted in the untimely end of the Hans' groundship threat.

"Those ships can't climb out of deep holes, Boss," he was saying excitedly. "Lay a big barrage against them—no, not on them—in front of them—always in front of them. Pull it back as they come on. But churn h—l out of the ground in front of them! Get the rocketmen to make a penetrative time rocket. Shoot it into the ground in front of them, deep enough to be below their canopy ray, see, and detonate under them as they go over it!"

I heard Handan's roar of exultation as I switched off again to order a barrage from my Wyoming girls. Then I threw my rocket motor to full speed and shot off a mile to one side, and higher, for I knew that soon there would be a boiling eruption below.

No smoke interfered with my view of it, for our atomic explosive was smokeless in its action. A line of blinding, flashing fire appeared in front of the groundship wedge. The ships ploughed with calm determination toward it, but it withdrew before them, not steadily, but jerkily intermittent, so that the ground became a series of gigantic humps, ridges and shell holes. Into these the Han ships wallowed, plunging ponderously yet not daring to stop while their protective canopy rays played, not daring to shut off these active rays.

One overturned. Our observers reported it. The result was a hail of rocket shells directly on the squadron. These could not penetrate the canopies of the other ships, but the one which had turned turtle was blown to fragments.

The squadron attempted to change its course and dodge the barrier in front of it. But a new barrier of blazing detonations and churned earth appeared on its flanks. In a matter of minutes it was ringed around, thanks to the skill of our fire control.

One by one the wallowing ships plunged into holes from which they could not extricate themselves. One by one their canopy rays were shut off, or the ships somersaulted off the knolls on which they perched, as their canopies melted the ground away from around them. So one by one they were destroyed.

Thus the second ground sortie of the Hans was annihilated.

At this period the Hans of Nu-Yok had only one airship equipped with their new armored repeller ray, their latest defense against our tactics of shooting rockets into the repeller rays and letting the latter hurl them up against the ships. They had developed a new steel alloy of tremendous strength, which passed their rep ray with ease, but was virtually impervious to our most powerful explosives. Their supplies of this alloy were limited, for it could be produced only in the Lo-Tan shops, for it was only there that they could develop the degree of electronic power necessary for its manufacture.

This ship shot out toward our lines just as the last of the groundships turned turtle and was blown to pieces. As it approached, the rockets of our invisible and widely scattered gunners in the forest below began to explode beneath its rep ray plates. The explosions caused the great ship to plunge and roll mightily, but otherwise did it no serious harm that I could see, for it was very heavily armored.

Occasionally rockets fired directly at the ship would find their mark and tear gashes in its side and bottom plates, but these hits were few. The ship was high in the air, and a far more difficult target than were its rep ray columns. To hit the latter, our gunners had only to gauge their aim vertically. Range could be practically ignored, since the rep ray at any point above two-thirds the distance from the earth to the ship would automatically hurl the rocket upward against the rep ray plate.

As the ship sped toward us, rocking, plunging and recovering, it began to beam the forest below. It was equipped with a superbeam too, which cut a swathe nearly a hundred feet wide wherever it played.

With visions of many a life snuffed out below me, I surrendered to the impulse to stage a single-handed attack on this ship, feeling quite secure in my floating shell of inertron. I nosed up vertically, and rocketed for a position above the ship. Then as I climbed upward, as yet unobserved in my tiny craft that was scarcely larger than myself, I trained my telultroscope on the Han ship, focussing through to a view of its interior.

Much as I had imbibed of this generation's hatred for the Hans, I was forced to admire them for the completeness and efficiency of this marvelous craft of theirs.

Constantly twirling the controls of my scope to hold the focus, I examined its interior from nose to stern.

It may be of interest at this point to give the reader a layman's explanation of the electronic or ionic machinery of these ships, and of their general construction, for today the general public knows little of the particular application of the electronic laws which the Hans used, although the practical application of ultronics are well understood.

Back in the Twentieth Century I had, like literally millions of others, dabbled a bit in "radio" as we called it then; the science of the Hans was simply the superdevelopment of "electricity," "radio," and "broadcasting."

It must be understood that this explanation of mine is not technically accurate, but only what might be termed an illustrative approximation.

The Hans' power-stations used to broadcast three distinct "powers" simultaneously. Our engineers called them the "starter," the "pullee" and the "sub-disintegrator." The last named had nothing to do with the operation of the ships, but was exclusively the powerizer of the disintegrator generators.

The "starter" was not unlike the "radio" broadcasts of the Twentieth Century. It went out at a frequency of about 1,000 kilocycles, had an amperage of approximately zero, but a voltage of two billion. Properly amplified by the use of inductostatic batteries (a development of the principle underlying the earth induction compass applied to the control of static) this current energized the "A" ionomagnetic coils on the airships, large and sturdy affairs, which operated the Attractoreflex Receivers, which in turn "pulled in" the second broadcast power known as the "pullee," absorbing it from every direction, literally exhausting it from surrounding space. The "pullee" came in at about a half-billion volts, but in very heavy amperage, proportional to the capacity of the receiver, and on a long wave—at audio frequency in fact. About half of this power reception ultimately actuated the repeller ray generators. The other half was used to energize the "B" ionomagnetic coils, peculiarly wound affairs, whose magnetic fields constituted the only means of insulating and controlling the circuits of the three "powers."

The repeller ray generators, operating on this current, and in conjunction with "twin synchronizers" in the power broadcast plant, developed two rhythmically variable ether-ground circuits of opposite polarity. In the "X" circuit, the negative was grounded along an ultraviolet beam from the ship's repeller-ray generator. The positive connection was through the ether to the "X synchronizer" in the power plant, whose opposite pole was grounded. The "Y" circuit travelled the same course, but in the opposite direction.

The rhythmic variables of these two opposing circuits, as nearly as I can understand it, in heterodyning, created a powerful material "push" from the earth, up along the violet ray beam against the rep ray generator and against the two synchronizers at the power plant.

This push developed molecularly from the earth-mass-resultant to the generator; and at the same fractional distance from the rep ray generator to the power plant.

The force exerted upward against the ship was, of course, highly concentrated, being confined to the path of the ultraviolet beam. Air or any material substance, coming within the indicated section of the beam, was thrown violently upward. The ships actually rode on columns of air thus forcefully up-thrown. Their "home berths" and "stations" were constructed with air pits beneath. When they rose from ordinary ground in open country, there was a vast upheaval of earth beneath their generators at the instant of take-off; this ceased as they got well above ground level.

Equal pressure to the lifting power of the generator was exerted against the synchronizers at the power plant, but this force, not being concentrated directionally along an ultraviolet beam, involved a practical problem only at points relatively close to the synchronizers.

Of course the synchronizers were automatically controlled by the operation of the generators, and only the two were needed for any number of ships drawing power from the station, providing their protection was rugged enough to stand the strain.

Actually, they were isolated in vast spherical steel chambers with thick walls, so that nothing but air pressure would be hurled against them, and this, of course, would be self-neutralizing, coming as it did from all directions.

The "sub-disintegrator power" reached the ships as an ordinary broadcast reception at a negligible amperage, but from one to 500 "quints" (quintillions) voltage, controllable only by the fields of the "B" ionomagnetic coils. It had a wave-length of about ten meters. In the dis ray generator, this wave-length was broken up into an almost unbelievably high frequency, and became a directionally controlled wave of an infinitesimal fraction of an inch. This wave-length, actually identical with the diameter of an electron, that is to say, being accurately "tuned" to an electron, disrupted the orbital paths and balanced pulsations of the electrons within the atom, so desynchronizing them as to destroy polarity balance of the atom and causing it to cease to exist as an atom. It was in this way that the ray reduced matter to "nothingness."

This destruction of the atom, and a limited power for its reconstruction under certain conditions, marked the utmost progress of the Han science.

Our own engineers, working in shielded laboratories far underground, had established such control over the "de-atomized" electrons as to dissect them in their turn into sub-electrons. Moreover, they had carried through the study of this "order" to the point where they finally "dissected" the sub-electron into its component ultrons, for the fundamental laws underlying these successive orders are not radically dissimilar. And as they progressed, they developed constructive as well as destructive practice. Hence the great triumphs of ultron and inertron, our two wonderful synthetic elements, built up from super-balanced and sub-balanced ultronic whorls, through the sub-electronic order into the atomic and molecular.

Hence also, come our relatively simple and beautifully efficient ultrophones and ultroscopes, which in their phonic and visual operation penetrate obstacles of material, electronic and sub-electronic nature without let or hindrance, and with the consumption of but infinitesimal power.

Static disturbance, I should explain, is negligible in the sub-electronic order, and non-existent in the ultronic.

The pioneer expeditions of our engineers into the ultronic order, I am told, necessitated the use of most elaborate, complicated and delicate apparatus, as well as the expenditure of most costly power, but once established there, all necessary power is developed very simply from tiny batteries composed of thin plates of metultron and katultron. These two substances, developed synthetically in much the same manner as ordinary ultron, exhibit dual phenomena which for sake of illustration I may compare with certain of the phenomena of radioactivity. As radium is constantly giving off electronic emanations and changing its atomic structure thereby, so katultron is constantly giving off ultronic emanations, and so changing its sub-electronic form, while metultron, its complement, is constantly attracting and absorbing ultronic values, and so changing its sub-electronic nature in the opposite direction. Thin plates of these two substances, when placed properly in juxtaposition, with insulating plates of inertron between, constitute a battery which generates an ultronic current.

And it is a curious parallel that just as there were many mysteries connected with the nature of electricity in the Twentieth Century (mysteries which, I might mention, never have been solved, notwithstanding our penetration into the "sub-" orders) so there are certain mysteries about the ultronic current. It will flow, for instance, through an ultron wire, from the katultron to the metultron plate, as electricity will flow through a copper wire. It will short circuit between the two plates if the inertron insulation is imperfect. When the insulation is perfect, however, and no ultron metallic circuit is complete, the "current" (apparently the same that would flow through the metallic circuit) is projected into space in an absolutely straight line from the katultron plate, and received from space by the metultron plate on the same line. This line is the theoretical straight line passing through the mass-center of each plate. The shapes and angles of the plates have nothing to do with it, except that the perpendicular distance of the plate edges from the mass-center line determines thickness of the beam of parallel current-rays.

Thus a simple battery may be used either as a sender or receiver of current. Two batteries adjusted to the same center line become connected in series just as if they were connected by ultron wires.

In actual practice, however, two types of batteries are used; both the foco batteries and broadcast batteries.

Foco batteries are twin batteries, arranged to shoot a positive and a negative beam in the same direction. When these beams are made intermittent at light frequencies (though they are not light waves, nor of the same order as light waves) and are brought together, or focussed, at a given spot, the space in which they cross radiates alternating ultronic current in every direction. This radiated ultralight acts like true light so long as the crossing beams vibrate at light frequencies, except in three respects: first, it is not visible to the eye; second, its "color" is exclusively dependent on the frequency of the foco beams, which determine the frequency of the alternating radiation. Material surfaces, it would appear, reflect them all in equal value, and the color of the resultant picture depends on the color of the foco frequencies. By altering these, a reddish, yellowish or bluish picture may be seen. In actual practice an orthochromatic mixture of frequencies is used to give a black, gray and white picture. The third difference is this: rays pulsating in line toward any ultron object connected with the rear plates of the twin batteries through rectifiers cannot be reflected by material objects, for it appears they are subject to a kind of "pull" which draws them straight through material objects, which in a sense are "magnetized" and while in this state offer no resistance.

Ultron, when so connected with battery terminals, glows with true light under the impact of ultralight, and if in the form of a lens or set of lenses, may be made to deliver a picture in any telescopic degree desired.

The essential parts of an ultroscope, then, are twin batteries with focal control and frequency control; an ultron shield, battery connected and adjustable, to intercept the direct rays from the "glow-spot," with an ordinary light-shield between it and the lens; and the lens itself, battery connected and with more or less telescopic elaboration.

To look through a substance at an object, one has only to focus the glow-spot beyond the substance but on the near side of the object and slightly above it.

A complete apparatus may be "set" for "penetrative," "distance" and "normal vision."

In the first, which one would use to look through the forest screen from the air, or in examining the interior of a Han ship or any opaque structure, the glow-spot is brought low, at only a tiny angle above the vision line, and the shield, of course, must be very carefully adjusted.

"Distance" setting would be used, for instance, in surveying a valley beyond a hill or mountain; the glow-spot is thrown high to illuminate the entire scene.

In the "normal" setting the foco rays are brought together close overhead, and illuminate the scene just as a lamp of super brilliancy would in the same position.

For phonic communication a spherical sending battery is a ball of metultron, surrounded by an insulating shell of inertron, and this in turn by a spherical shell of katultron, from which the current radiates in every direction, tuning being accomplished by frequency of intermissions, with audio-frequency modulation. The receiving battery has a core pole of katultron and an outer shell of metultron. The receiving battery, of course, picks up all frequencies, the undesired ones being tuned out in detection.

Tuning, however, is only a convenience for privacy and elimination of interference in ultrophonic communication. It is not involved as a necessity, for untuned currents may be broadcast at voice-controlled frequencies, directly and without any carrier wave.

To use plate batteries or single center-line batteries for phonic communication would require absolutely accurate directional aligning of sender and receiver, a very great practical difficulty, except when sender and receiver are relatively close and mutually visible.

This, however, is the regular system used in the Inter-Gang network for official communication. The senders and receivers used in this system are set only with the greatest difficulty, and by the aid of the finest laboratory apparatus, but once set, they are permanently locked in position at the stations, and barring earthquakes or insecure foundations, need no subsequent adjustment. Accuracy of alignment permits beam paths no thicker than the old lead pencils I used to use in the Twentieth Century.

The non-interference of such communication lines, and the difficulty of cutting in on them from any point except immediately adjacent to the sender or receiver, is strikingly apparent when it is realized that every square inch of an imaginary plane bisecting the unlocated beam would have to be explored with a receiving battery in order to locate the beam itself.

A practical compromise between the spherical or universal broadcast senders and receivers on the one hand, and the single line batteries on the other, is the multi-facet battery. Another, and more practical device particularly for distance work, is the window-spherical. It is merely an ordinary spherical battery with a shielding shell with an opening of any desired size, from which a directionally controlled beam may be emitted in different forms, usually that simply of an expanding cone, with an angle of expansion sufficient to cover the desired territory at the desired point of reception.

But to return to my narrative, and my swooper, from which I was gazing at the interior of the Han ship.

This ship was not unlike the great dirigibles of the Twentieth Century in shape, except that it had no suspended control car nor gondolas, no propellers, and no rudders, aside from a permanently fixed double-fishtail stabilizer at the rear, and a number of "keels" so arranged as to make the most of the repeller ray airlift columns.

Its width was probably twice as great as its depth, and its length about twice its width. That is to say, it was about 100 feet from the main keel to the top-deck at their maximum distance from each other, about 200 feet wide amidship, and between 400 and 500 feet long. It had in addition to the top-deck, three interior decks. In its general curvature the ship was a compromise between a true streamline design and a flattened cylinder.

For a distance of probably 75 to 100 feet back of the nose there were no decks except that formed by the bottom of the hull. But from this point back the decks ran to within a few feet of the stern.

At various spots on the hull curvature in this great "hollow nose" were platforms from which the crews of the dis ray generators and the electronoscope and electronophone devices manipulated their apparatus.

Into this space from the forward end of the center deck, projected the control room. The walls, ceiling and floor of this compartment were simply the surfaces of viewplates. There were no windows or other openings.

The operation officers within the control room, so far as their vision was concerned, might have imagined themselves suspended in space, except for the transmitters, levers and other signalling devices around them.

Five officers, I understand, had their posts in the control room; the captain, and the chiefs of scopes, phones, dis rays and navigation. Each of these was in continuous interphone communication with his subordinates in other posts throughout the ship. Each viewplate had its phone connecting with its "eye machines" on the hull, the crews of which would switch from telescopic to normal view at command.

There were, of course, many other viewplates at executive posts throughout the ship.

The Hans followed a peculiar system in the command of their ships. Each ship had a double complement of officers. Active Officers and Base Officers. The former were in actual, active charge of the ship and its apparatus. The latter remained at the ship base, at desks equipped with viewplates and phones, in constant communication with their "correspondents," on the ship. They acted continuously as consultants, observers, recorders and advisors during the flight or action. Although not primarily accountable for the operation of the ship, they were senior to, and in a sense responsible for the training and efficiency of the Active Officers.

The ionomagnetic coils, which served as the casings, "plates" and insulators of the gigantic condensers, were all located amidship on a center line, reaching clear through from the top to the bottom of the hull, and reaching from the forward to the rear rep-ray generators; that is, from points about 110 feet from bow and stern. The crew's quarters were arranged on both sides of the coils. To the outside of these, where the several decks touched the hull, were located the various pieces of phone, scope and dis ray apparatus.

The ship into which I was gazing with my ultroscope (at a telescopic and penetrative setting), carried a crew of perhaps 150 men all told. And except for the strained looks on their evil yellow faces I might have been tempted to believe I was looking on some Twenty-fifth Century pleasure excursion, for there was no running around nor appearance of activity.

The Hans loved their ease, and despite the fact that this was a war ship, every machine and apparatus in it was equipped with a complement of seats and specially designed couches, in which officers and men reclined as they gazed at their viewplates, and manipulated the little sets of controls placed convenient to their hands.

The picture was a comic one to me, and I laughed, wondering how such soft creatures had held the sturdy and virile American race in complete subjection for centuries. But my laugh died as my mind grasped at the obvious explanation. These Hans were only soft physically. Mentally they were hard, efficient, ruthless, and conscienceless.

Impulsively I nosed my swooper down toward the ship and shot toward it at full rocket power. I had acted so swiftly that I had covered nearly half the distance toward the ship before my mind slowly drifted out of the daze of my emotion. This proved my undoing. Their scopeman saw me too quickly, for in heading directly at them I became easily visible, appearing as a steady, expanding point. Looking through their hull, I saw the crew of a dis ray generator come suddenly to attention. A second later their beam engulfed me.

For an instant my heart stood still. But the inertron shell of my swooper was impervious to the disintegrator ray. I was out of luck, however, so far as my control over my tiny ship was concerned. I had been hurtling in a direct line toward the ship when the beam found me. Now, when I tried to swerve out of the beam, the swooper responded but sluggishly to the shift I made in the rocket angle. I was, of course, traveling straight down a beam of vacuum. As my craft slowly nosed to the edge of the beam, the air rushing into this vacuum from all sides threw it back in again.

Had I shot my ship across one of these beams at right angles, my momentum would have carried me through with no difficulty. But I had no momentum now except in the line of the beam, and this being a vacuum now, my momentum, under full rocket power, was vastly increased. This realization gave me a second and more acute thrill. Would I be able to check my little craft in time, or would I, helpless as a bullet itself, crash through the shell of the Han ship to my own destruction?

I shut off my rocketmotor, but noticed no practical diminution of speed.

It was the fear of the Hans themselves that saved me. Through my ultroscope I saw sudden alarm on their faces, hesitation, a frantic officer in the control room jabbering into his phone. Then shakily the crew flipped their beam off to the side. The jar on my craft was terrific. Its nose caught the rushing tumble of air first, of course, and my tail sailing in a vacuum, swung around with a sickening wrench. My swooper might as well have been a barrel in the tumult of waters at the foot of Niagara. What was worse, the Hans kept me in that condition. Three of their beams were now playing in my direction, but not directly on me except for split seconds. Their technique was to play their beams around me more than on me, jerking them this way and that, so as to form vacuum pockets into which the air slapped and roared as the beams shifted, tossing me around like a chip.

Desperately I tried to bring my craft under control, to point its nose toward the Han ship and discharge an explosive rocket. Bitterly I cursed my self-confidence, and my impulsive action. An experienced pilot of the present age would have known better than to be caught shooting straight down a dis ray beam. He would have kept his ship shooting constantly at some angle to it, so that his momentum would carry him across it if he hit it. Too late I realized that there was more to the business of air fighting, than instinctive skill in guiding a swooper.

At last, when for a fraction of a second my nose pointed toward the Hans, I pressed the button of my rocket gun. I registered a hit, but not an accurate one. My projectile grazed an upper section of the ship's hull. At that it did terrific damage. The explosion battered in a section about fifty feet in diameter, partially destroying the top deck.

At the same instant I had shot my rocket, I had, in a desperate attempt to escape that turmoil of tumbling air, released a catch and dropped all that it was possible to drop of my ultron ballast. My swooper shot upward, like a bubble streaking for the surface of water.

I was free of the trap in which I had been caught, but unable to take advantage of the confusion which reigned on the Han ship.

I was as helpless to maneuver my ship now, in its up-rush, as when I had been tumbling in the air pockets. Moreover I was badly battered from plunging around in my shell like a pellet in a box, and partially unconscious.

I was miles in the air when I recovered myself. The swooper was steady enough now, but still rising, my instruments told me, and traveling in a general westward direction at full speed. Far below me was a sea of clouds, stretching from horizon to horizon, and through occasional breaks in its surface I could see still other seas of clouds at lower levels.

Certainly my situation was no less desperate. Unless I could find some method of compensating for my lost ballast, the inverse gravity of my inertron ship would hurl me continuously upward until I shot forth from the last air layer into space. I thought of jumping, and floating down on my inertron belt, but I was already too high for this. The air was too rarefied to permit breathing outside, though my little air compressors were automatically maintaining the proper density within the shell. If I could compress a sufficiently large quantity of air inside the craft, I would add to its weight. But there seemed little chance that I would myself be able to withstand sufficient compression.

I thought of releasing my inertron belt, but doubted whether this would be enough. Besides I might need the belt badly if I did find some method of bringing the little ship down, and it came too fast.

At last a plan came into my half-numbed brain that had some promise of success, though it was desperate enough. Cutting one of the hose pipes on my air compressor, and grasping it between my lips, I set to work to saw off the heads of the rivets that held the entire nose section of the swooper (inertron plates had to be grooved and riveted together, since the substance was impervious to heat and could not be welded). Desperately I sawed, hammered and chiseled, until at last with a wrench and a snap, the plate broke away.

The released nose of the ship shot upward. The rest began to drop with me. How fast I dropped I do not know, for my instruments went with the nose. Half fainting, I grimly clenched the rubber hose between my teeth, while the little compressor "carried on" nobly, despite the wrecked condition of the ship, giving me just enough air to keep my lungs from collapsing.

At last I shot through a cloud layer, and a long time afterward, it seemed, another. From the way in which they flashed up to meet me and to appear away above me, I must have been dropping like a stone.

At last I tried the rocket motor, very gently, to check my fall. The swooper was, of course, dropping tail first, and I had to be careful lest it turn over with a sharp blast from the motor, and dump me out.

Passing through the third layer of clouds I saw the earth beneath me. Then I jumped, pulling myself up through the jagged opening, and leaping upward while the remains of my ship shot away below me.

On approaching the ground I opened my chute-cape, to further check my fall, and landed lightly, with no further mishap. Whereupon I promptly threw myself down and slept, so exhausted was I with my experience.

It was not until the next morning that I awoke and gazed about me. I had come down in mountainous country. My intention was to get my bearing by tuning in headquarters with my ultrophone. But to my dismay I found the little battery disks had been torn from the earflaps of my helmet, though my chest-disk transmitter was still in place, and so far as I could see, in working order. I could report my experience, but could receive no reply.

I spent a half hour repeating my story and explanation on the headquarters channel, then once more surveyed my surroundings, trying to determine in which direction I had better leap. Then there came a stab of pain on the top of my head, and I dropped unconscious.

I regained consciousness to find myself, much to my surprise, a prisoner in the hands of a foot detachment of some thirty Hans. My surprise was a double one; first that they had not killed me instantly; second, that a detachment of them should be roaming this wild country afoot, obviously far from any of their cities, and with no ship hanging in the sky above them.

As I sat up, their officer grunted with satisfaction and growled a guttural command. I was seized and pulled roughly to my feet by four soldiers, and hustled along with the party into a wooded ravine, through which we climbed sharply upward. I surmised, correctly as it turned out, that some projectile had grazed my head, and I was in such shape that if it had not been for the fact that my inertron belt bore most of my weight, they would have had to carry me. But as it was I made out well, and at the end of an hour's climb was beginning to feel like myself again, though the Han soldiers around me were puffing and drooping as men will, no matter how healthy, when they are totally unaccustomed to physical effort.

At length the party halted for a rest. I observed them curiously. Except for a few brief exciting moments at the time of our air raid on the intelligence office in Nu-Yok, I had seen no living specimens of this yellow race at close quarters.

They looked little like the Mongolians of the Twentieth Century, except for their slant eyes and round heads. The characteristic of the high cheek bones appeared to have been bred out of them, as were those of the relatively short legs and the muddy yellow skin. To call them yellow was more figurative than literal. Their skins were whiter than those of our own weather-tanned forest men. Nevertheless, their pigmentation was peculiar, and what there was of it looked more like a pale orange tint than the ruddiness of the Caucasian. They were well formed, but rather undersized and soft-looking, small-muscled and smooth-skinned, like young girls. Their features were finely chiseled, eyes beady, and nose slightly aquiline.

They were uniformed, not in close-fitting green or other shades of protective coloring, such as the unobtrusive gray of the Jersey Beaches or the leadened russet of the autumn uniforms of our people. Instead they wore loose fitting jackets of some silky material, and loose knee pants. This particular command had been equipped with form-moulded boots of some soft material that reached above the knee under their pants. They wore circular hats with small crowns and wide rims. Their loose jackets were belted at the waist, and they carried for weapons each man a knife, a short double-edged sword and what I took to be a form of magazine rocket gun. It was a rather bulky affair, short-barrelled, and with a pistol grip. It was obviously intended to be fired either from the waist position or from some sort of support, like the old machine guns. It looked, in fact, like a rather small edition of the Twentieth Century arm.

And have I mentioned the color of their uniforms? Their circular hats and pants were a bright yellow; their coats a flaming scarlet. What targets they were!

I must have chuckled audibly at the thought, for their commander who was seated on a folding stool one of his men had placed for him, glanced in my direction, and, at his arrogant gesture of command, I was prodded to my feet, and with my hands still bound, as they had been from the moment I recovered consciousness, I was dragged before him.

Then I knew what it was about these Hans that kept me in a turmoil of irritation. It was their sardonic, mocking, cruel smiles; smiles which left their stamp on their faces, even in repose. Now the commander was smiling tauntingly at me. When he spoke, it was in my own language.

"So!" he sneered. "You beasts have learned to laugh. You have gotten out of control in the last year or so. But that shall be remedied. In the meantime, a simple little surgical operation would make your smile a permanent one, reaching from ear to ear. But there, my orders are to deliver you and your equipment, all we have of it, intact. The Heaven-Born has had a whim."

"And who," I asked, "is this Heaven-Born?"

"San-Lan," he replied, "misbegotten spawn of the late High Priestess Nlui-Mok, and now Most Glorious Air Lord of All the Hans." He rolled out these titles with a bow of exaggerated respect toward the west, and in a tone of mockery. Those of his men who were near enough to hear, snickered and giggled.

I was to learn that this amazing attitude of his was typical rather than exceptional. Strange as it may seem, no Han rendered any respect to another, nor expected it in return; that is, not genuine respect. Their discipline was rigid and cold-bloodedly heartless. The most elaborate courtesies were demanded and accorded among equals and from inferiors to superiors, but such was the intelligence and moral degradation of this remarkable race, that every one of them recognized these courtesies for what they were; they must of necessity have been hollow mockeries. They took pleasure in forcing one another to go through with them, each trying to outdo the other in cynical, sardonic thrusts, clothed in the most meticulously ceremonious courtesy. As a matter of fact, my captor, by this crude reference to the origin of his ruler, was merely proving himself a crude fellow, guilty of a vulgarity rather than of a treasonable or disrespectful remark. An officer of higher rank and better breeding, would have managed a clever innuendo, less direct, but equally plain.

I was about to ask him what part of the country we were in and where I was to be taken, when one of his men came running to him with a little portable electronophone, which he placed before him, with much bowing and scraping.

He conversed through this for a while, and then condescended to give me the information that a ship would soon be above us, and that I was to be transferred to it. In telling me this, he managed to convey, with crude attempts at mock-courtesy, that he and his men would feel relieved to be rid of me as a menace to health and sanitation, and would take exquisite joy in inflicting me upon the crew of the ship.

Some twenty minutes later the ship arrived. It settled down slowly into the ravine on its repeller rays until it was but a few feet above the tree tops. There it was stopped, and floated steadily, while a little cage was let down on a wire. Into this I was hustled and locked, whereupon the cage rose swiftly again to a hole in the bottom of the hull, into which it fitted snugly, and I stepped into the interior of a craft not unlike the one with which I had had my fateful encounter, the cage being unlocked.

The cabin in which I was confined was not an outside compartment, but was equipped with a number of viewplates.

The ship rose to a great height, and headed westward at such speed that the hum of the air past its smooth plates rose to a shrill, almost inaudible moan. After a lapse of some hours we came in sight of an impressive mountain range, which I correctly guessed to be the Rockies. Swerving slightly, we headed down toward one of the topmost pinnacles of the range, and there unfolded in one of the viewplates in my cabin a glorious view of Lo-Tan, the Magnificent, a fairy city of glistening glass spires and iridescent colors, piled up on sheer walls of brilliant blue, on the very tip of this peak.

Nor was there any sheen of shimmering disintegrator rays surrounding it, to interfere with the sparkling sight. So far-flung were the defenses of Lo-Tan, I found, that it was considered impossible for an American rocket gunner to get within effective range, and so numerous were the dis ray batteries on the mountain peaks and in the ravines, in this encircling line of defenses, drawn on a radius of no less than 100 miles, that even the largest craft, in the opinion of the Hans, could easily be brought to earth through air-pocketing tactics. And this, I was the more ready to believe after my own recent experience.

I spent two months as a prisoner in Lo-Tan. I can honestly say that during that entire time every attention was paid to my physical comfort. Luxuries were showered upon me. But I was almost continuously subjected to some form of mental torture or moral assault. Most elaborately staged attempts at seduction were made upon me with drugs, with women. Hypnotism was resorted to. Viewplates were faked to picture to me the complete rout of American forces all over the continent. With incredible patience, and laboring under great handicaps, in view of the vigor of the American offensive, the Han intelligence department dug up the fact that somewhere in the forces surrounding Nu-Yok, I had left behind me Wilma, my bride of less than a year. In some manner, I will never tell how, they discovered some likeness of her, and faked an electronoscopic picture of her in the hands of torturers in Nu-Yok, in which she was shown holding out her arms piteously toward me, as though begging me to save her by surrender.

Surrender of what? Strangely enough, they never indicated that to me directly, and to this day I do not know precisely what they expected or hoped to get out of me. I surmise that it was information regarding the American sciences.

There was, however, something about the picture of Wilma in the hands of the torturers that did not seem real to me, and my mind still resisted. I remember gazing with staring eyes at that picture, the sweat pouring down my face, searching eagerly for some visible evidence of fraud and being unable to find it. It was the identical likeness of Wilma. Perhaps had my love for her been less great, I would have succumbed. But all the while I knew subconsciously that this was not Wilma. Product of the utmost of nobility in this modern virile, rugged American race, she would have died under even worse torture than these vicious Han scientists knew how to inflict, before she would have pleaded with me this way to betray my race and her honor.

But these were things that not even the most skilled of the Han hypnotists and psychoanalysts could drag from me. Their intelligence division also failed to pick up the fact that I was myself the product of the Twentieth Century and not the Twenty-fifth. Had they done so, it might have made a difference. I have no doubt that some of their most subtle mental assaults missed fire because of my own Twentieth Century "denseness." Their hypnotists inflicted many horrifying nightmares on me, and made me do and say many things that I would not have done in my right senses. But even in the Twentieth Century we had learned that hypnotism cannot make a person violate his fundamental concepts of morality against his will, and steadfastly I steeled my will against them.

I have since thought that I was greatly aided by my newness to this age. I have never, as a matter of fact, become entirely attuned to it. And even today I confess to a longing wish that man might travel backward as well as forward in time. Now that my Wilma has been at rest these many years, I wish that I might go back to the year 1927, and take up my old life where I left it off, in the abandoned mine near Scranton.

And at the period of which I speak, I was less attuned than now to the modern world. Real as my life was, and my love for my wife, there was much about it all that was like a dream, and in the midst of my tortures by the Hans, this complex—this habit of many months—helped me to tell myself that this, too, was all a dream, that I must not succumb, for I would wake up in a moment.

And so they failed.

More than that, I think I won something nearer to genuine respect from those around me than any other Hans of that generation accorded to anybody.

Among these was San-Lan himself, the ruler. In the end it was he who ordered the cessation of these tortures, and quite frankly admitted to me his conviction that they had been futile and that I was in many senses a super-man. Instead of having me executed, he continued to shower luxuries and attentions on me, and frequently commanded my attendance upon him.

Another was his favorite concubine, Ngo-Lan, a creature of the most alluring beauty; young, graceful and most delicately seductive, whose skill in the arts and sciences put many of their doctors to shame. This creature, his most prized possession, San-Lan with the utmost moral callousness ordered to seduce me, urging her to apply without stint and to its fullest extent, her knowledge of evil arts. Had I not seen the naked horror of her soul, that she let creep into her eyes for just one unguarded instant, and had it not been for my conviction of Wilma's faith in me, I do not know what—but suffice it to say that I resisted this assault also.

Had San-Lan only known it, he might have had a better chance of breaking down my resistance through another bit of femininity in his household, the little nine-year-old Princess Lu-Yan, his daughter.

I think San-Lan held something of real affection for this sprightly little mite, who in spite of the sickening knowledge of rottenness she had already acquired at this early age, was the nearest thing to innocence I found in Lo-Tan. But he did not realize this, and could not; for even the most natural and fundamental affection of the human race, that of parents for their offspring, had been so degraded and suppressed in this vicious Han civilization as to be unrecognizable. Naturally San-Lan could not understand the nature of my pity for this poor child, nor the fact that it might have proved a weak spot in my armor. But had he done so, I truly believe he would have been ready to inflict degradation, torture and even death upon her, to make me surrender the information he wanted.

Yet this man, perverted product of a morally degraded race, had about him something of true dignity; something of sincerity, in a warped, twisted way. There were times when he seemed to sense vaguely, gropingly, wonderingly, that he might have a soul.

The Han philosophy for centuries had not admitted the existence of souls. Its conception embraced nothing but electrons, protons and molecules, and still was struggling desperately for some shred of evidence that thoughts, will power and consciousness of self were nothing but chemical reactions. However, it had gotten no further than the negative knowledge we had in the Twentieth Century, that a sick body dulls consciousness of the material world, and that knowledge, which all mankind has had from the beginning of time, that a dead body means a departed consciousness. They had succeeded in producing, by synthesis, what appeared to be living tissues, and even animals of moderately complex structure and rudimentary brains, but they could not give these creatures the full complement of life's characteristics, nor raise the brains to more than mechanical control of muscular tissues.

It was my own opinion that they never could succeed in doing so. This opinion impressed San-Lan greatly. I had expected him to snort his disgust, as the extreme school of evolutionists would have done in the Twentieth Century. But the idea was as new to him and the scientists of his court as Darwinism was to the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries. So it was received with much respect. Painfully and with enforced mental readjustments, they began a philosophical search for excuses and justifications for the idea.

All of this amused me greatly, for of course neither the newness nor the orthodoxy of a hypothesis will make it true if it is not true, nor untrue if it is true. Nor could the luck or will-power, with which I had resisted their hypnotists and psychoanalysts, make what might or might not be a universal fact one whit more or less of a fact than it really was. But the prestige I had gained among them, and the novelty of my expressed opinion carried much weight with them.

Yet, did not even brilliant scientists frequently exhibit the same lack of logic back in the Twentieth Century? Did not the historians, the philosophers of ancient Greece and Rome show themselves to be the same shrewd observers as those of succeeding centuries, the same masters of the logical and slaves of the illogical?

After all, I reflected, man makes little progress within himself. Through succeeding generations he piles up those resources which he possesses outside of himself, the tools of his hands, and the warehouses of knowledge for his brain, whether they be parchment manuscripts, printed book, or electronorecordographs. For the rest he is born today, as in ancient Greece, with a blank brain, and struggles through to his grave, with a more or less beclouded understanding, and with distinct limitations to what we used to call his "think tank."

This particular reflection of mine proved unpopular with them, for it stabbed their vanity, and neither my prestige nor the novelty of the idea was sufficient salve. These Hans for centuries had believed and taught their children that they were a super-race, a race of destiny. Destined to Whom, for What, was not so clear to them; but nevertheless destined to "elevate" humanity to some sort of super-plane. Yet through these same centuries they had been busily engaged in the extermination of "weaklings," whom, by their very persecutions, they had turned into "super men," now rising in mighty wrath to destroy them; and in reducing themselves to the depths of softening vice and flabby moral fiber. Is it strange that they looked at me in amazed wonder when I laughed outright in the midst of some of their most serious speculations?

My position among the Hans, in this period, was a peculiar one. I was at once a closely guarded prisoner and an honored guest. San-Lan told me frankly that I would remain the latter only so long as I remained an object of serious study or mental diversion to himself or his court. I made bold to ask him what would be done with me when I ceased to be such.

"Naturally," he said, "you will be eliminated. What else? It takes the services of fifteen men altogether, to guard you; and men, you understand, cannot be produced and developed in less than eighteen years." He meditated frowningly for a moment. "That, by the way, is something I must take up with the Birth and Educational Bureau. They must develop some method of speeding growth, even at the cost of mental development. With your wild forest men getting out of hand this way, we are going to need greater resources of population, and need them badly.