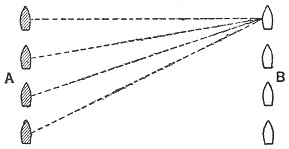

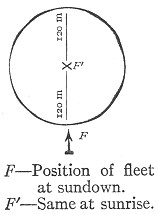

Fig. 1

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Navy as a Fighting Machine

Author: Bradley A. Fiske

Release Date: January 18, 2006 [eBook #17547]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE NAVY AS A FIGHTING MACHINE***

BY

U. S. NAVY

What is the navy for?

Of what parts should it be composed?

What principles should be followed in designing, preparing, and operating it in order to get the maximum return for the money expended?

To answer these questions clearly and without technical language is the object of the book.

BRADLEY A. FISKE.

U. S. NAVAL WAR COLLEGE,

NEWPORT, R. I., September 3, 1916.

| PART I | |

| GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS | |

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | WAR AND THE NATIONS |

| II. | NAVAL A, B, C |

| III. | NAVAL POWER |

| IV. | NAVAL PREPAREDNESS |

| V. | NAVAL DEFENSE |

| VI. | NAVAL POLICY |

| PART II | |

| NAVAL STRATEGY | |

| VII. | GENERAL PRINCIPLES |

| VIII. | DESIGNING THE MACHINE |

| IX. | PREPARING THE ACTIVE FLEET |

| X. | RESERVES AND SHORE STATIONS |

| XI. | NAVAL BASES |

| XII. | OPERATING THE MACHINE |

STRATEGIC MAP OF THE ATLANTIC AND PACIFIC OCEANS

*** Chapters III and VII were published originally in The U. S. Naval Institute; chapters I, II, IV, V, and VII in The North American Review.

PART I

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

WAR AND THE NATIONS

Because the question is widely discussed, whether peace throughout the world may be attained by the friendly co-operation of many nations, and because a nation's attitude toward this question may determine its future prosperity or ruin, it may be well to note what has been the trend of the nations hitherto, and whether any forces exist that may reasonably be expected to change that trend. We may then be able to induce from facts the law which that trend obeys, and make a reasonable deduction as to whether or not the world is moving toward peace. If we do this we shall follow the inductive method of modern science, and avoid the error (with its perilous results) of first assuming the law and then deducing conclusions from it.

Men have always been divided into organizations, the first organization being the family. As time went on families were formed into tribes, for self-protection. The underlying cause for the organization was always a desire for strength; sometimes for defense, sometimes for offense, usually for both.

At times tribes joined in alliance with other tribes to attain a common end, the alliance being brought about by peaceful agreement, and usually ceasing after the end had been attained, or missed, or when tribal jealousies forbade further common effort. Sometimes tribes joined to form one larger tribe; the union being either forced on a weaker by a stronger tribe, or caused by a desire to secure a strength greater and more lasting than mere alliance can insure.

In the same way, and apparently according to similar laws, sovereign states or nations were formed from tribes; and in later years, by the union of separate states. The states or nations have become larger and larger as time has gone on; greater numbers, not only of people but of peoples, living in the same general localities and having hereditary ties, joining to form a nation.

Though the forms of government of these states or nations are numerous, and though the conceptions of people as to the purposes and functions of the state vary greatly, we find that one characteristic of a state has always prevailed among all the states and nations of the world—the existence of an armed military force, placed under the control of its government; the purpose of this armed force being to enable the government not only to carry on its administration of internal matters, but also to exert itself externally against the armed force of another state.

This armed force has been a prominent factor in the life of every sovereign state and independent tribe, from history's beginning, and is no less a factor now. No instance can be found of a sovereign state without its appropriate armed force, to guard its sovereignty, and preserve that freedom from external control, without which freedom it ceases to exist as a sovereign state.

The armed force has always been a matter of very great expense. It has always required the anxious care of the government and the people. The men comprising it have always been subjected to restraint and discipline, compelled to undergo hardships and dangers greater than those of civil life, and developed by a training highly specialized and exacting.

The armed force in every state has had not only continuous existence always, but continuous, potential readiness, if not continuous employment; and the greatest changes in the mutual relations of nations have been brought about by the victory of the armed force of one state over the armed force of another state. This does not mean that the fundamental causes of the changes have been physical, for they have been psychological, and have been so profound and so complex as to defy analysis; but it does mean that the actual and immediate instrument producing the changes has been physical force; that physical force and physical courage acting in conjunction, of which conjunction war is the ultimate expression, have always been the most potent instruments in the dealings of nations with each other.

Is there any change toward peaceful methods now?

No, on the contrary; war is recognized as the most potent method still; the prominence of military matters is greater than ever before; at no time in the past has interest in war been so keen as at the present, or the expenditure of blood and money been so prodigal; at no time before has war so thoroughly engaged the intellect and energy of mankind.

In other words, the trend of the nations has been toward a clearer recognition of the efficacy of military power, and an increasing use of the instrumentality of war.

This does not mean that the trend of the nations has been regular; for, on the contrary, it has been spasmodic. If one hundred photographs of the map of Europe could be taken, each photograph representing in colors the various countries as they appeared upon the map at one hundred different times, and if those hundred photographs could be put on films and shown as a moving-picture on a screen, the result would resemble the shifting colored pieces in a kaleidoscope. Boundaries advanced and receded, then advanced again; tribes and nations moved their homes from place to place; empires, kingdoms, principalities, duchies, and republics flourished brilliantly for a while, and then went out; many peoples struggled for an autonomous existence, but hardly a dozen acquired enough territory or mustered a sufficiently numerous population to warrant their being called "great nations." Of those that were great nations, only three have endured as great nations for eight hundred years; and the three that have so endured are the three greatest in Europe now—the French, the British, and the German.

Some of the ancient empires continued for long periods. The history of practical, laborious, and patient China is fairly complete and clear for more than two thousand years before our era; and of dreamy, philosophic India for almost as long, though in far less authentic form. Egypt existed as a nation, highly military, artistic, and industrious, as her monuments show, for perhaps four thousand years; when she was forced by the barbarians of Persia into a condition of dependence, from which she has never yet emerged. The time of her greatness in the arts and sciences of peace was the time of her greatest military power; and her decline in the arts and sciences of peace accompanied her decline in those of war. Assyria, with her two capitals, Babylon and Nineveh, flourished splendidly for about six centuries, and was then subdued by the Persians under Cyrus, after the usual decline. The little kingdom of the Hebrews, hardy and warlike under Saul and David, luxurious and effeminate under Solomon, lasted but little more than a hundred years. Persia, rising rapidly by military means from the barbarian state, lived a brilliant life of conquest, cultivated but little those arts of peace that hold in check the passions of a successful military nation, yielded rapidly to the seductions of luxury, and fell abruptly before the Macedonian Alexander, lasting less than two hundred and fifty years. Macedonia, trained under Philip, rose to great military power under Alexander, conquered in twelve years the ten most wealthy and populous countries of the world—nearly the whole known world; but fell to pieces almost instantly when Alexander died. The cities of Greece enjoyed a rare pre-eminence both in the arts and sciences of peace and in military power, but only for about one hundred and fifty years: falling at last before the superior military force of Macedon, after neglecting the practice of the military arts, and devoting themselves to art, learning, and philosophy. Rome as a great nation lasted about five hundred years; and the last three centuries of her life after the death of Commodus, about 192 A. D., illustrate curiously the fact that, even if a people be immoral, cruel, and base in many ways, their existence as an independent state may be continued long, if military requirements be understood, and if the military forces be preserved from the influence of the effeminacy of the nation as a whole. In Rome, the army was able to maintain a condition of considerable manliness, relatively to the people at large, and thus preserve internal order and keep the barbarians at bay for nearly three hundred years; and at the same time exert a powerful and frequently deciding influence in the government. But the effeminacy of the people, especially of those in the higher ranks, made them the creatures of the army that protected them. In some cases, the Emperor himself was selected by the army, or by the Pretorian Guard in Rome; and sometimes the guard removed an Emperor of whom it disapproved by the simple expedient of killing him.

After the fall of the Western Empire in 476, when Rome was taken by Odoacer, a condition of confusion, approaching anarchy, prevailed throughout Europe, until Charlemagne founded his empire, about 800 A. D., except that Constantinople was able to stand up against all outside assaults and hold the Eastern Empire together. Charlemagne's empire united under one government nearly all of what is now France, Germany, Austria, Italy, Belgium, and Holland. The means employed by Charlemagne to found his empire were wholly military, though means other than military were instituted to preserve it. He endeavored by just government, wise laws, and the encouragement of religion and of education of all kinds to form a united people. The time was not ripe, however; and Charlemagne's empire fell apart soon after Charlemagne expired.

The rapid rise and spread of the Mohammedan religion was made possible by the enthusiasm with which Mahomet imbued his followers, but the actual founding of the Arabian Empire was due wholly to military conquest, achieved by the fanatic Mussulmans who lived after him. After a little more than a hundred years, the empire was divided into two caliphates. Brilliant and luxurious courts were thereafter held by caliphs at Bagdad and Cordova, with results similar to those in Egypt, Persia, Assyria, and Rome; the people becoming effeminate, employed warriors to protect them, and the warriors became their masters. Then, effeminacy spreading even to the warriors, strength to resist internal disorders as well as external assaults gradually faded, and both caliphates fell.

From the death of Charlemagne until the fall of Constantinople, in 1453, the three principal nations of Europe were those of France, Germany, and England. Until that time, and dating from a time shortly before the fall of Rome, Europe was in perpetual turmoil—owing not only to conflicts between nations, but to conflicts between the Church of Rome and the civil power of the Kings and Emperors, to conflicts among the feudal lords, and to conflicts between the sovereigns and the feudal lords. The power of the Roman Church was beneficent in checking a too arrogant and military tendency, and was the main factor in preventing an utter lapse back to barbarism.

The end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of what are usually called "Modern Times" found only four great countries in the world—France, Germany, Spain, and England. Of these Spain dropped out in the latter part of the sixteenth century. The other three countries still stand, though none of them lies within exactly the same boundaries as when modern times began; and Austria, which was a part of Germany then, is now—with Hungary—a separate state and nation.

This very brief survey of history shows that every great nation has started from a small beginning and risen sometimes gradually, sometimes rapidly to greatness; and then fallen, sometimes gradually, sometimes rapidly, to mediocrity, dependence, or extinction; that the instrument which has effected the rise has always been military power, usually exerted by armies on the land, sometimes by navies on the sea; and that the instrument which has effected the actual fall has always been the military power of an adversary. In other words, the immediate instrument that has decided the rise and the fall of nations has been military power.

That this should have been so need not surprise us, since nations have always been composed of human beings, influenced by the same hopes and fears and governed by the same laws of human nature. And as the most potent influence that could be brought to bear upon a man was a threat against his life, and as it was the province of military power to threaten life, it was unavoidable that military power should be the most potent influence that could be brought to bear upon a nation.

The history of the world has been in the main a history of war and a narrative of wars. No matter how far back we go, the same horrible but stimulating story meets our eyes. In ancient days, when every weapon was rude, and manipulated by one man only, the injury a single weapon could do was small, the time required for preparation was but brief, and the time required for recuperation after war was also brief. At that time, military power was almost the sole element in the longevity of a tribe, or clan, or nation; and the warriors were the most important men among the people. But as civilization increased, the life not only of individuals but of nations became more complex, and warriors had to dispute with statesmen, diplomatists, poets, historians, and artists of various types, the title to pre-eminence. Yet even in savage tribes and even in the conduct of savage wars, the value of wisdom and cunning was perceived, and the stimulating aid of the poet and the orator was secured. The relative value of men of war and men of peace depended during each period on the conditions prevailing then—in war, warriors held the stage; in peace, statesmen and artists had their day.

Naturally, during periods when war was the normal condition, the warrior was the normal pillar of the state. In how great a proportion of the time that history describes, war was the normal condition and peace the abnormal, few realize now in our country, because of the aloofness of the present generation from even the memory of war. Our last great war ended in 1865; and since then only the light and transient touch of the Spanish War has been laid upon us. Even that war ended seventeen years ago and since then only the distant rumblings of battles in foreign lands have been borne across the ocean to our ears.

These rumblings have disturbed us very little. Feeling secure behind the 3,000-mile barrier of the ocean, we have lent an almost incredulous ear to the story that they tell and the menace that they bear; though the story of the influence of successful and unsuccessful wars upon the rise and fall of nations is told so harshly and so loudly that, in order not to hear it, one must tightly stop his ears.

That war has not been the only factor, however, in the longevity of nations is obviously true; and it is also true that nations which have developed the warlike arts alone have never even approximated greatness. In all complex matters, in all processes of nature and human nature, many elements are present, and many factors combine to produce a given result. Man is a very complex individual, and the more highly he is developed the more complex he becomes. A savage is mainly an animal; but the civilized and highly educated man is an animal on whose elemental nature have been superposed very highly organized mental, moral, and spiritual natures. Yet even a savage of the most primitive or warlike character has an instinctive desire for rest and softness and beauty, and loves a primitive music; and even the most highly refined and educated gentleman raises his head a little higher, and draws his breath a little deeper, when war draws near. Thus in the breast of every man are two opposing forces; one urging him to the action and excitement of war, the other to the comparative inaction and tranquillity of peace. On the side that urges war, we see hate, ambition, courage, energy, and strength; on the side that urges peace we see love, contentment, cowardice, indolence, and weakness. We see arrayed for war the forceful faults and virtues; for peace the gentle faults and virtues. Both the forceful and the gentle qualities tend to longevity in certain ways and tend to its prevention in other ways; but history clearly shows that the forceful qualities have tended more to the longevity of nations than the gentle. If ever two nations, or two tribes, have found themselves contiguous, one forceful and the other not, the forceful one has usually, if not always, obtained the mastery over the other, and therefore has outlived it. If any cow and any lion have found themselves alone together, the lion has outlived the cow.

It is true that the mere fact of being a lion has not insured long life, and that the mere fact of being a cow has not precluded it; and some warlike tribes and nations have not lived so long as tribes and nations of softer fibre. This seems to have been due, however, either to the environments in which the two have lived, or to the fact that the softer nation has had available some forces that the other did not have. The native Indians of North America were more warlike than the colonists from Europe that landed on their shores; but the Indians were armed with spears and arrows, and the colonists with guns.

Now, those guns were the product of the arts of peace; no nation that had pursued a warlike life exclusively could have produced them or invented the powder that discharged them. This fact indicates what a thousand other facts of history also indicate, that civilization and the peaceful arts contribute to the longevity of nations—not only by promoting personal comfort, and by removing causes of internal strife, and thus enabling large bodies of people to dwell together happily, but also by increasing their military power. Every nation which has achieved greatness has cultivated assiduously both the arts of peace and the arts of war. Every nation which has long maintained that greatness has done so by maintaining the policy by which she acquired it. Every nation that has attained and then lost greatness, has lost it by losing the proper balance between the military and the peaceful arts; never by exalting unduly the military, but always by neglecting them, and thereby becoming vulnerable to attack.

In other words, the history of every great nation that has declined shows three periods, the rise, the table-land of greatness, and the decline. During the rise, the military arts hold sway; on the table-land, the arts of peace and war are fairly balanced; during the decline the peaceful arts hold sway. Facilis descensus Averni. The rise is accomplished by expending energy, for which accomplishment the possession of energy is the first necessity; the height of the table-land attained represents the amount of energy expended; the length of time that the nation maintains itself upon this table-land, before starting on the inevitable descent therefrom, represents her staying power and constitutes her longevity as a great nation.

How long shall any nation stay upon the table-land? As long as she continues to adapt her life wisely to her environment; as long as she continues to be as wise as she was while climbing up; for while climbing, she had not only to exert force, she had also to guide the force with wisdom. So we see that, in the ascent, a nation has to use both force and wisdom; on the table-land, wisdom; in the decline, neither. Among the nations of antiquity one might suppose that, because of the slowness of transportation and communication, and the feebleness of weapons compared with those of modern days, much longer periods of time would be required for the rise of any nation, and also a longer period before her descent began. Yet the vast empire of Alexander lasted hardly a day after he expired, and the Grecian cities maintained their greatness but a century and a half; while Great Britain, France, and Germany have been great nations for nearly a thousand years.

Why have they endured longer than the others?

The answer is hard to find; because many causes, and some of them obscure, have contributed to the result. But, as we observe the kind of constitution and the mode of life of long-lived people, in order to ascertain what kind of constitution and mode of life conduce to longevity in people, so perhaps we may logically do the same with nations.

Observing the constitution and mode of life of the British, French, and German nations, we are struck at once with the fact that those peoples have been by constitution active, ambitious, intelligent, and brave; and that they have observed in their national life a skilfully balanced relation between the arts of peace and the arts of war; neglecting neither and allowing neither to wax great at the expense of the other. In all those countries the first aim has been protection from both external attack and internal disorder. Protection from external attack has been gained by military force and highly trained diplomacy; protection from internal disorder has been gained first by military force, and second by wise laws, just courts, and the encouragement of religion and of those arts and sciences that lead to comfort and happiness in living.

China may attract the attention of some as an instance of longevity; but is China a nation in the usual meaning of the word? Certainly, she is not a great nation. It is true that no other nation has actually conquered her of late; but this has been largely by reason of her remoteness from the active world, and because other nations imposed their will upon her, without meeting any resistance that required the use of war to overcome. And even China has not lived a wholly peaceful life, despite the non-military character of her people. Her whole history was one of wars, like that of other nations, until the middle of the fourteenth century of our era. Since then, she has had four wars, in all of which she has been whipped: one in the seventeenth century when the country was successfully invaded, and the native dynasty was overthrown by the Tartars of Manchuria; one in 1840, when Great Britain compelled her to cede Hong-Kong and to open five ports to foreign commerce, through which ports opium could be introduced; one in 1860, with Great Britain and France, that resulted in the capture of Pekin; and one with Japan in 1894. Since that time (as well as before) China has been the scene of revolutions and wide-spread disturbances, so that, even though a peace-loving and non-resisting nation, peace has not reigned within her borders. The last dynasty was overthrown in 1912. Since then a feeble republic has dragged on a precarious existence, interrupted by the very short reign of Yuan Shih K'ai.

This brief consideration of the trend of people up to the present time seems to show that, owing to the nature of man himself, especially to the nature of large "crowds" of men, the direction in which nations have been moving hitherto has not been toward increasing the prevalence of peace, but rather toward increasing the methods, instruments, and areas of war; furthermore, that this direction of movement has been necessary, in order to achieve and to maintain prosperity in any nation.

This being the case, what forces exist that may reasonably be expected to change that trend?

Three main forces are usually mentioned: Civilization, Commerce, Christianity.

Before considering these it may be well to note Newton's first law of motion, that every body will continue in a state of rest or of uniform motion in a straight line unless acted on by some external force; for though this law was affirmed of material bodies, yet its applicability to large groups of men is striking and suggestive. Not only do human beings have the physical attributes of weight and inertia like other material bodies, but their mental organism, while of a higher order than the physical, is as powerfully affected by external forces. And though it is true that psychology has not yet secured her Newton, and that no one has yet formulated a law that expresses exactly the action of the minds and spirits of men under the influence of certain mental and moral stimuli or forces, yet we know that our minds and spirits are influenced by fear, hope, ambition, hate, and so forth, in ways that are fairly well understood and toward results that often can be predicted in advance.

Our whole theory of government and our laws of business and every-day life are founded on the belief that men are the same to-day as they were yesterday, and that they will be the same to-morrow. The whole science of psychology is based on the observed and recorded actions of the human organism under the influence of certain external stimuli or forces, and starts from the assumption that this organism has definite and permanent characteristics. If this is not so—if the behavior of men in the past has not been governed by actual laws which will also govern their behavior in the future—then our laws of government are built on error, and the teachings of psychology are foolish.

This does not mean that any man will necessarily act in the same way to-morrow as he did yesterday, when subjected to the influence of the same threat, inducement, or temptation; because, without grappling the thorny question of free will, we realize that a man's action is never the result of only one stimulus and motive, but is the resultant of many; and we have no reason to expect that he will act in the same way when subjected to the same stimulus, unless we know that the internal and external conditions pertaining to him are also the same. Furthermore, even if we cannot predict what a certain individual will do, when exposed to a certain external influence, because of some differences in his mental and physical condition, on one occasion in comparison with another, yet when we consider large groups of men, we know that individual peculiarities, permanent and temporary, balance each other in great measure; that the average condition of a group of men is less changeable than that of one man, and that the degree of permanency of condition increases with the number of men in the group. From this we may reasonably conclude that, if we know the character of a man—or a group of men—and if we know also the line of action which he—or they-have followed in the past, we shall be able to predict his—or their—line of action in the future with considerable accuracy; and that the accuracy will increase with the number of men in the group, and the length of time during which they have followed the known line of action. Le Bon says: "Every race carries in its mental constitution the laws of its destiny."

Therefore, the line of action that the entire human race has followed during the centuries of the past is a good index—or at least the best index that we have—to its line of action during the centuries of the future.

Now, men have been on this earth for many years; and history and psychology teach us that in their intercourse with each other, their conduct has been caused by a combination of many forces, among which are certain powerful forces that tend to create strife. The strongest by far of these forces is the ego in man himself, a quality divinely implanted which makes a man in a measure self-protecting. This ego prompts a man not only to seek pleasure and avoid trouble for himself, but also to gain superiority, and, if possible, the mastery over his fellow men. Men being placed in life in close juxtaposition to each other, the struggles of each man to advance his own interests produce rivalries, jealousies, and conflicts.

Similarly with nations. Nations have been composed for the most part of people having an heredity more or less common to them all, so that they are bound together as great clans. From this it has resulted that nations have been jealous of each other and have combated each other. They have been doing this since history began, and are doing it as much as ever now.

In fact, mankind have been in existence for so many centuries, and their physical, moral, mental, and spiritual characteristics were so evidently implanted in them by the Almighty, that it seems difficult to see how any one, except the Almighty himself, can change these characteristics and their resulting conduct. It is a common saying that a man cannot lift himself over the fence by his boot straps, though he can jump over the fence, if it is not too high. This saying recognizes the fact that "a material system can do no work on itself"; but needs external aid. When a man pulls upward on his boot straps, the upward force that he exerts is exactly balanced by the downward reaction exerted by his boot straps; but when he jumps, the downward thrust of his legs causes an equal reaction of the earth, which exerts a direct force upward upon the man; and it is this external force that moves him over the fence. It is this external force, the reaction of the earth or air or water, which moves every animal that walks, or bird that flies, or fish that swims. It is the will of the Almighty, acting through the various stimuli of nature, that causes the desire to walk, and all the emotions and actions of men. If He shall cause any new force to act on men, their line of conduct will surely change. But if He does not—how can it change, or be changed; how can the human race turn about, by means of its own power only, and move in a direction the reverse from that in which it has been moving throughout all the centuries of the past?

These considerations seem to indicate that nations, regarded in their relation toward each other, will go on in the direction in which they have been going unless acted upon by some external force.

Will civilization, commerce, or Christianity impart that force?

Inasmuch as civilization is merely a condition in which men live, and an expression of their history, character and aims, it is difficult to see how it could of itself act as an external force, or cause an external force to act. "Institutions and laws," says Le Bon, again, "are the outward manifestation of our character, the expression of its needs. Being its outcome, institutions and laws cannot change this character."

Even if the civilization of a given nation may have been brought about in some degree by forces external to that nation, yet it is clear that we must regard that civilization rather as the result of those forces than as a force itself. Besides, civilization has never yet made the relations of nations with each other more unselfish, civilized nations now and in the past, despite their veneer of courtesy, being fully as jealous of each other as the most savage tribes. That this should be so seems natural; because civilization has resulted mainly from the attempts of individuals and groups to enhance the pleasures and diminish the ills of life, and therefore cannot tend to unselfishness in either individuals or nations. Civilization in the past has not operated to soften the relations of nations with each other, so why should it do so now? Is not modern civilization, with its attendant complexities, rivalries, and jealousies, provocative of quarrels rather than the reverse? In what respect is modern civilization better than past civilization, except in material conveniences due to material improvements in the mechanic arts? Are we any more artistic, strong, or beautiful than the Greeks in their palmy days? Are we braver than the Spartans, more honest than the Chinese, more spiritual than the Hindoos, more religious than the Puritans? Is not the superior civilization of the present day a mechanical civilization pure and simple? And has not the invention of electrical and mechanical appliances, with the resulting insuring of communication and transportation, and the improvements in instruments of destruction, advantaged the great nations more than the weaker ones, and increased the temptation to great nations to use force rather than decreased it? Do not civilization's improvements in weapons of destruction augment the effectiveness of warlike methods, as compared with the peaceful methods of argument and persuasion?

Diplomacy is an agency of civilization that was invented to avoid war, to enable nations to accommodate themselves to each other without going to war; but, practically, diplomacy seems to have caused almost as many wars as it has averted. And even if it be granted that the influence of diplomacy has been in the main for peace rather than for war, we know that diplomacy has been in use for centuries, that its resources are well understood, and that they have all been tried out many times; and therefore we ought to realize clearly that diplomacy cannot introduce any new force into international politics now, or exert, an influence for peace that will be more potent in the future than the influence that it has exerted in the past.

These considerations seem to show that we cannot reasonably expect civilization to divert nations from the path they have followed hitherto.

Can commerce impart the external force necessary to divert nations from that path?

Since commerce bears exactly the same relation to nations now as in times past, and since it is an agency within mankind itself, it is difficult to see how it can act as an external force, or cause an external force to be applied. Of course, commercial interests are often opposed to national interests, and improvements in speed and sureness of communication and transportation increase the size and power of commercial organizations. But the same factors increase the power of governments and the solidarity of nations. At no time in the past has there been more national feeling in nations than now. Even the loosely held provinces of China are forming a Chinese nation. Despite the fundamental commercialism of the age, national spirit is growing more intense, the present war being the main intensifying cause. It is true that the interests of commerce are in many ways antagonistic to those of war. But, on the other hand, of all the causes that occasion war the economic causes are the greatest. For no thing will men fight more savagely than for money; for no thing have men fought more savagely than for money; and the greater the rivalry, the more the man's life becomes devoted to it, and the more fiercely he will fight to get or keep it. Surely of all the means by which we hope to avoid war, the most hopeless by far is commerce.

The greatest of all hopes is in Christianity, because of its inculcation of love and kindliness, its obvious influence on the individual in cultivating unselfishness and other peaceful virtues, and the fact that it is an inspiration from on high, and therefore a force external to mankind. But let us look the facts solemnly in the face that the Christian religion has now been in effect for nearly two thousand years; that the nations now warring are Christian nations, in the very foremost rank of Christendom; that never in history has there been so much bloodshed in such wide-spread areas and so much hate, and that we see no signs that Christianity is employing any influence that she has not been employing for nearly two thousand years.

If we look for the influence of Christianity, we can find it in the daily lives of people, in the family, in business, in politics, and in military bodies; everywhere, in fact, in Christian countries, so long as we keep inside of any organization the members of which feel bound together. This we must all admit, even the heathen know it; but where do we see any evidence of the sweetening effect of Christianity in the dealings of one organization with another with which it has no special bonds of friendship? Christianity is invoked in every warring nation now to stimulate the patriotic spirit of the nation and intensify the hate of the crowd against the enemy; and even if we think that such invoking is a perversion of religious influence to unrighteous ends, we must admit the fact that the Christian religion itself is at this moment being made to exert a powerful influence—not toward peace but toward war! And this should not amaze us; for where does the Bible say or intimate that love among nations will ever be brought about? The Saviour said: "I bring not peace but a sword." So what reasonable hope does even Christianity give us that war between nations will cease? And even if it did give reasonable hope, let us realize that between reasonable hope and reasonable expectation there is a great gulf fixed.

Therefore, we seem forced to the conclusion that the world will move in the future in the same direction as in the past; that nations will become larger and larger and fewer and fewer, the immediate instrument of international changes being war; and that certain nations will become very powerful and nearly dominate the earth in turn, as Persia, Greece, Rome, Spain, France, and Great Britain have done—and as some other country soon may do.

Fortunately, or perhaps unfortunately, a certain law of decadence seems to have prevailed, because of which every nation, after acquiring great power, has in turn succumbed to the enervating effects which seem inseparable from it, and become the victim of some newer nation that has made strenuous preparations for long years, in secret, and finally pounced upon her as a lion on its prey.

Were it not for this tendency to decadence, we should expect that the nations of the earth would ultimately be divided into two great nations, and that these would contend for the mastery in a world-wide struggle.

But if the present rate of invention and development continues, improvements in the mechanic arts will probably cause such increase in the power of weapons of destruction, and in the swiftness and sureness of transportation and communication, that some monster of efficiency will have time to acquire world mastery before her period of decadence sets in.

In this event, wars will be of a magnitude besides which the present struggle will seem pygmy; and will rage over the surface of the earth, for the gaining and retaining of the mastery of the world.

NAVAL A, B, C

In order to realize what principles govern the use of navies, let us first consider what navies have to do and get history's data as to what navies in the past have done. It would obviously be impossible to recount here all the doings of navies. But neither is it necessary; for the reason that, throughout the long periods of time in which history records them, their activities have nearly always been the same.

In all cases in which navies have been used for war there was the preliminary dispute, often long-continued, between two peoples or their rulers, and at last the decision of the dispute by force. In all cases the decision went to the side that could exert the most force at the critical times and places. The fact that the causes of war have been civil, and not military, demands consideration, for the reason that some people, confusing cause and effect, incline to the belief that armies and navies are the cause of war, and that they are to be blamed for its horrors. History clearly declares the contrary, and shows that the only rôle of armies and navies has been to wage wars, and, by waging, to finish them.

It may be well here, in order to clear away a possible preconception by the reader, to try and dispel the illusion that army and navy officers are eager for war, in order that they may get promotion. This idea has been exploited by people opposed to the development of the army and navy, and has been received with so much credulity that it seriously handicaps the endeavors of officers to get an unbiassed hearing. But surely the foolishness of such an idea would promptly disappear from the brain of any one if he would remind himself that simply because a man joins the army or navy he does not cease to be a human being, with the same emotions of fear as other men, the same sensitiveness to pain, the same dread of death, and the same horror of leaving his family unsupported after his death. It is true that men in armies and navies are educated to dare death if need be; but the present writer has been through two wars, has been well acquainted with army and navy officers for forty-five years, and knows positively that, barring exceptions, they do not desire war at all.

Without going into an obviously impossible discussion of all naval wars, it may be instructive to consider briefly the four naval wars in which the United States has engaged.

The first was the War of the American Revolution. This war is instructive to those who contend that the United States is so far from Europe as to be safe from attack by a European fleet; because the intervening distance was frequently traversed then by British and French fleets of frail, slow, sailing ships, which were vital factors in the war. Without the British war-ships, the British could not have landed and supported their troops. Without the French war-ships the French could not have landed and supported their troops, who, under Rochambeau, were also under Washington, and gave him the assistance that he wofully needed, to achieve by arms our independence.

The War of 1812 is instructive from the fact that, though the actions of our naval ships produced little material effect, the skill, daring, and success with which they were fought convinced Europeans of the high character and consequent noble destiny of the American people. The British were so superior in sea strength, however, that they were able to send their fleet across the ocean and land a force on the shores of Chesapeake Bay. This force marched to Washington, attacked the city, and burned the Capitol and other public buildings, with little inconvenience to itself.

The War of the Rebellion is instructive because it shows how two earnest peoples, each believing themselves right, can be forced, by the very sincerity of their convictions, to wage war against each other; and because it shows how unpreparedness for war, with its accompanying ignorance of the best way in which to wage it, causes undue duration of a war and therefore needless suffering. If the North had not closed its eyes so resolutely to the fact of the coming struggle, it would have noted beforehand that the main weakness of the Confederacy lay in its dependence on revenue from cotton and its inability to provide a navy that could prevent a blockade of its coasts; and the North would have early instituted a blockade so tight that the Confederacy would have been forced to yield much sooner than it did. The North would have made naval operations the main effort, instead of the auxiliary effort; and would have substituted for much of the protracted and bloody warfare of the land the quickly decisive and comparatively merciful warfare of the sea.

In the Spanish War the friction between the United States and Spain was altogether about Cuba. No serious thought of the invasion of either country was entertained, no invasion was attempted, and the only land engagements were some minor engagements in Cuba and the Philippines. The critical operations were purely naval. In the first of these, Commodore Dewey's squadron destroyed the entire Far Eastern squadron of the Spanish in Manila Bay; in the second, Admiral Sampson's squadron destroyed the entire Atlantic squadron of the Spanish near Santiago de Cuba. The two naval victories compelled Spain to make terms of peace practically as the United States wished. Attention is invited to the fact that this war was not a war of conquest, was not a war of aggression, was not a war of invasion, was not a war carried on by either side for any base purpose; but was in its intention and its results for the benefit of mankind.

The Russo-Japanese War was due to conflicting national policies. While each side accused the other of selfish ends, it is not apparent to a disinterested observer that either was unduly selfish in its policy, or was doing more than every country ought to advance the interests and promote the welfare of its people. Russia naturally had a great deal of interest in Manchuria, and felt that she had a right to expand through the uncivilized regions of Manchuria, especially since she needed a satisfactory outlet to the sea. In other words, the interests of Russia were in the line of its expanding to the eastward. But Japan's interests were precisely the reverse of Russia's—that is, Japan's interests demanded that Russia should not do those things that Russia wanted to do. Japan felt that Russia's movement toward the East was bringing her entirely too close to Japan. Russia was too powerful a country, and too aggressive, to be trusted so close. Japan had the same feeling toward Russia that any man might have on seeing another man, heavily armed, gradually coming closer to him in the night. Japan especially wished that Russia should have no foothold in Corea, feeling, as she expressed it, that the point of Corea under Russian power would be a dagger directed at the heart of Japan. This feeling about Corea was the same feeling that every country has about land near her; it has a marked resemblance to the feeling that the United States has embodied in Monroe Doctrine.

After several years of negotiation in which Japan and Russia endeavored to secure their respective aims by diplomacy, diplomacy was finally abandoned and the sword taken up instead. Japan, because of the superior foresight of her statesmen, was the first to realize that diplomacy must fail, was the first to realize that she must prepare for war, was the first to begin adequate preparation for war, was the first to complete preparation for war, was the first to strike, and in consequence was the victor. Yet Russia was a very much larger, richer, more populous country than Japan.

Russia sent large forces of soldiers to Manchuria by the trans-Siberian railroad, and Japan sent large forces there by transports across the Sea of Japan. Japan could not prevent the passage of soldiers by the railroad, but Russia could prevent the passage of transports across the Japan Sea, provided her fleet could overcome the Japanese fleet and get command of the sea. Russia had a considerable fleet in the Far East; but she had so underestimated the naval ability of the Japanese, that the Russian fleet proved unequal to the task; and the Japanese gradually reduced it to almost nothing, with very little loss to themselves.

Russia then sent out another fleet. The Japanese met this fleet on the 27th of May, 1904, near the Island of Tsushima, between Corea and Japan. The battle was decided in about an hour. The Japanese sank practically all the Russian ships before the battle was entirely finished, with comparatively small loss to Japan. This battle was carried on 12,000 miles by sea route from Saint Petersburg. No invasion of Russia or Japan was contemplated, or attempted, and yet the naval battle decided the issue of the war completely, and was followed by a treaty of peace very shortly afterward.

These wars show us, as do all wars in which navies have engaged, that the function of a navy is not only to defend the coast in the sense of preventing an enemy from landing on it, but also to exert force far distant from the coast. The study of war has taught its students for many centuries that a merely passive defense will finally be broken down, and that the most effective defense is the "offensive-defensive."

Perhaps the clearest case of a correct offensive-defensive is Nelson's defense of England, which he carried on in the Mediterranean, in the West Indies, and wherever the enemy fleet might be, finally defeating Napoleon's plan for invading England—not by waiting off the coast of England, but by attacking and crippling Napoleon's fleet off the Spanish coast near Trafalgar.

The idea held by many people that the defense of a country can be effected by simply preventing the invasion of its coasts, is a little like the notion of uneducated people that a disease can be cured by suppressing its symptoms. For even a successful defense of a coast against invasion by a hostile force cannot remove the inimical influence to a country's commerce and welfare which that hostile force exerts, any more than palliatives can cure dyspepsia. Every intelligent physician knows that the only way to cure a disease is to remove its cause; and every intelligent military or naval man knows that history teaches that the only way in which a country can defend itself successfully against an enemy is to defeat the armed force of that enemy—be it a force of soldiers on the land, or a force of war-ships on the sea. In naval parlance, "our objective is the enemy's fleet."

If the duty of a navy be merely to prevent the actual invasion of its country's coasts, a great mistake has been made by Great Britain, France, and other countries in spending so much money on their navies, and in giving so much attention to the education and training of their officers and enlisted men. To prevent actual invasion would be comparatively an easy task, one that could be performed by rows of forts along the coast, supplemented by mines and submarines. If that is the only kind of defense required, navies are hardly needed. The army in each country could man the forts and operate the mines, and a special corps of the army could even operate the submarines, which (if their only office is to prevent actual invasion) need hardly leave the "three-mile limit" that skirts the coasts. If the people of any country do not care to have dealings outside; if the nation is willing to be in the position of a man who is safe so long as he stays in the house, but is afraid to go outdoors, the problem of national defense is easy.

But if the people desire to prevent interference with what our Constitution calls "the general welfare," the problem becomes exceedingly complex and exceedingly grave—more complex and grave than any other problem that they have. If they desire that their ships shall be free to sail the seas, and their citizens to carry on business and to travel in other lands; and if they desire that their merchants shall be able to export their wares and their farmers their grain, also that the people shall be able to import the things they wish from foreign countries, then they must be able to exert actual physical force on the ocean at any point where vessels carrying their exports and imports may be threatened. Naval ships are the only means for doing this.

The possibility that an armed force sent to a given point at sea might have to fight an enemy force, brought about first the sending of more than one vessel, and later—as the mechanic arts progressed—the increasing of the size of individual vessels, and later still the development of novel types.

There are two main reasons for building a small number of large ships rather than a large number of small ships. The first reason is that large ships are much more steady, reliable, safe, and fast than small ships. The second reason is that, when designed for any given speed, the large ships have more space available for whatever is to be carried; one 15-knot ship of 20,000 tons normal displacement, for instance, has about one and a half times as much space available for cargo, guns, and what-not, as four 15-knot ships of 5,000 tons each. These two reasons apply to merchant ships as well as naval ships. A third reason applies to naval vessels only, and is that a few large ships can be handled much better together than a large number of small ships, and embody that "concentration of force" which it is the endeavor of strategy and tactics to secure. A fourth reason is the obvious one that large ships can carry larger guns than small ships.

The distinctly military (naval) purpose for which a war-ship is designed necessitates, first, that in addition to her ability to go rapidly and surely from place to place, she be able to exert physical force against an enemy ship or fort, and, second, that she have protection against the fire of guns and torpedoes from enemy ships and forts, against bombs dropped from aircraft, and against mines.

This means that a man-of-war, intended to exert the maximum of physical force against an enemy and to be able to withstand the maximum of punishment, must have guns and torpedoes for offense, and must have armor and cellular division of the hull for defense; the armor to keep out the enemy's shells, and the cellular division of the hull to prevent the admission of more water than can fill one water-tight compartment in case the ship is hit.

It must be admitted here that, at the present moment, torpedoes hold such large charges of explosive that the cellular division of ships does not adequately protect them. This means that a contest has been going on between torpedo-makers and naval constructors like the contest between armor-makers and gunmakers, and that just now the torpedo-makers are in the lead. For this reason a battleship needs other protection than that imparted by its cellular subdivision. This is given by its "torpedo defense battery" of minor guns of about 5-inch calibre.

By reason of the great vulnerability of all ships to attack below the water-line, the torpedo was invented and developed. In its original form, the torpedo was motionless in the water, either anchored to the ground, or floating on the surface, and was in fact what now is called a "mine." But forty-eight years ago an Englishman named Whitehead invented the automobile, auto-steering, torpedo, which still bears his name. This torpedo is used in all the navies, and is launched on its mission from battleships, battle cruisers, destroyers, submarines, and other craft of various kinds.

Most torpedoes are to be found in destroyers—long, fast, frail vessels, averaging about 700 tons displacement, that are intended to dash at enemy ships at night, or under other favorable conditions, launch their torpedoes, and hurry away. The torpedo is "a weapon of opportunity." It has had a long, slow fight for its existence; but its success during the present war has established it firmly in naval warfare.

The submarine has followed the destroyer, and some people think will supplant it; though its relatively slow speed prevents those dashes that are the destroyer's rôle. The submarine is, however, a kind of destroyer that is submersible, in which the necessities of submersibility preclude great speed. The submarine was designed to accomplish a clear and definite purpose—a secret under-water attack on an enemy's ship in the vicinity. It has succeeded so well in its limited mission that some intelligent people declare that we need submarines only—ignoring the fact that, even if submarines could successfully prevent actual invasion, they could not carry on operations at a distance from their base of supplies. It is true that submarines may be made so large that they can steam at great speed from place to place, as capital ships steam now, carry large supplies of fuel and food, house their crews hygienically, and need no "mother ship" or tender. But if submarines achieve such size, they will be more expensive to build and run than battleships—and will be, in fact, submersible battleships. In other words, the submarine cannot displace the battleship, but may be developed and evolved into a new and highly specialized type of battleship.

The necessity for operating at long distances from a base carries with it the necessity for supplying more fuel than even a battleship can carry; and this means that colliers must be provided. In most countries, the merchant service is so large that colliers can be taken from it, but in the United States no adequate merchant marine exists, and so it is found necessary to build navy colliers and have them in the fleet. The necessity for continuously supplying food and ammunition to the fleet necessitates supply ships and ammunition ships; but the problem of supplying food and ammunition is not so difficult as that of supplying fuel, for the reason that they are consumed more slowly.

In order to take care of the sick and wounded, and prevent them from hampering the activities of the well, hospital ships are needed. Hospital ships should, of course, be designed for that purpose before being constructed; but usually hospital ships were originally passenger ships, and were adapted to hospital uses later.

The menace of the destroyer—owing to the sea-worthiness which this type has now achieved, and to the great range which the torpedo has acquired—has brought about the necessity of providing external protection to the battleships; and this is supplied by a "screen" of cruisers and destroyers, whose duty is to keep enemy destroyers and (so far as is practicable) the submarines at a safe distance.

We now see why a fleet must be composed of various types of vessels. At the present moment, the battleship is the primary, or paramount type, the others secondary, because the battleship is the type that can exert the most force, stand the hardest punishment, steam the farthest in all kinds of weather, and in general, serve her country the best.

Of course, "battleship" is merely a name, and some think not a very good name, to indicate a ship that can take the part in battle that used to be taken by the "ship of the line." The reason for its primacy is fundamental: its displacement or total weight—the same reason that assured the primacy of the ship of the line. For displacement rules the waves; if "Britannia rules the waves," it is simply because Britannia has more displacement than any other Power.

The fleet needs to have a means of knowing where the enemy is, how many ships he has, what is their character, the direction in which they are steaming, and their speed. To accomplish this purpose, "scouts" are needed—fast ships, that can steam far in all kinds of weather and send wireless messages across great distances. So far as their scout duties go, such vessels need no guns whatever, and no torpedoes; but because the enemy will see the scout as soon as the scout sees the enemy, and because the enemy will try to drive away the scout by gun and torpedo fire, the scouts must be armed. And this necessity is reinforced by the necessity of driving off an enemy's scouts.

In foreign navies the need for getting information in defiance of an enemy's attempts to prevent it, and to drive off the armed scouts of an enemy, has been one of the prime reasons for developing "battle cruisers," that combine the speed of the destroyer with the long steaming radius of the battleship, a battery almost as strong, and a very considerable protection by armor.

The aeroplane and the air-ship are recent accessions to the list of fighting craft. Their rôle in naval warfare cannot yet be defined, because the machines themselves have not yet reached an advanced stage of development, and their probable performance cannot be forecast. There is no doubt, however, in the minds of naval men that the rôle of aircraft is to be important and distinguished.

NAVAL POWER

Mahan proved that sea power has exercised a determining influence on history. He proved that sea power has been necessary for commercial success in peace and military success in war. He proved that, while many wars have culminated with the victory of some army, the victory of some navy had been the previous essential. He proved that the immediate cause of success had often resulted inevitably from another cause, less apparent because more profound; that the operations of the navy had previously brought affairs up to the "mate in four moves," and that the final victory of the army was the resulting "checkmate."

Before Mahan proved his doctrine, it was felt in a general way that sea power was necessary to the prosperity and security of a nation. Mahan was not the first to have this idea, for it had been in the minds of some men, and in the policy of one nation, for more than a century. Neither was Mahan the first to put forth the idea in writing; but he was the first to make an absolute demonstration of the truth. Newton was not the first man to know, or to say, that things near the earth tend to fall to the earth; but he was the first to formulate and prove the doctrine of universal gravitation. In the same way, all through history, we find that a few master minds have been able to group what had theretofore seemed unrelated phenomena, and deduce from them certain laws. In this way they substituted reasoning for speculation, fact for fancy, wisdom for opportunism, and became the guides of the human race.

The effect of the acceptance of Mahan's doctrine was felt at once. Realizing that the influence of sea power was a fact, comprehending Great Britain's secret, after Mahan had disclosed it, certain other great nations of the world, especially Germany, immediately started with confidence and vigor upon the increase of their own sea power, and pushed it to a degree before unparalleled; with a result that must have been amazing to the man who, more than any other, was responsible for it.

Since the words "sea power," or their translation, is a recognized phrase the world over, and since the power of sea power is greater than ever before, and is still increasing, it may be profitable to consider sea power as an entity, and to inquire what are its leading characteristics, and in what it mainly consists.

There is no trouble in defining what the sea is, but there is a good deal of trouble in defining what power is. If we look in a dictionary, we shall find a good many definitions of power; so many as to show that there are many different kinds of power, and that when we read of "power," it is necessary to know what kind of power is meant. Clearly "sea power" means power on the sea. But what kind of power? There are two large classes into which power may be divided, passive and active. Certainly we seem justified, at the start, in declaring that the power meant by Mahan was not passive, but active. Should this be granted, we cannot be far from right if we go a step further, and declare that sea power means ability to do something on the sea.

If we ask what the something is that sea power has ability to do, we at once perceive that sea power may be divided into two parts, commercial power and naval power.

The power exerted by commercial sea power is clearly that exerted by the merchant service, and is mainly the power of acquiring money. It is true that the merchant service has the power of rendering certain services in war, especially the power of providing auxiliary vessels, and of furnishing men accustomed to the sea; but as time goes on the power contributable by the merchant service must steadily decrease, because of the relatively increasing power of the naval service, and the rapidly increasing difference between the characteristics of ships and men suitable for the merchant service and those suitable for the naval service.

But even in the past, while the importance of the merchant service was considerable in the ways just outlined, it may perhaps be questioned whether it formed an element of sea power, in the sense in which Mahan discussed sea power. The power of every country depends on all the sources of its wealth: on its agriculture, on its manufacturing activities, and even more directly on the money derived from exports. But these sources of wealth and all sources of wealth, including the merchant service, can hardly be said to be elements of power themselves, but rather to be elements for whose protection power is required.

In fact, apart from its usefulness in furnishing auxiliaries, it seems certain that the merchant service has been an element of weakness. The need for navies arose from the weakness of merchant ships and the corresponding necessity for assuring them safe voyages and proper treatment even in time of peace; while in time of war they have always been an anxious care, and have needed and received the protection of fighting ships that have been taken away from the fleet to act as convoys.

If commercial sea power was not the power meant by Mahan, then he must have meant naval power. And if one reads the pages of history with patient discrimination, the conviction must grow on him that what really constituted the sea power which had so great an influence on history, was naval power; not the power of simply ships upon the sea, but the power of a navy composed of ships able to fight, manned by men trained to fight, under the command of captains skilled to fight, and led by admirals determined to fight. Trafalgar was not won by the merchant service; nor Mobile, Manila, or Tsushima.

If sea power be essentially naval power, it may be interesting to inquire: In what does naval power consist and what are its principal characteristics?

If one looks at a fleet of war-ships on the sea, he will be impressed consciously or unconsciously with the idea of power. If he is impressed consciously, he will see that the fleet represents power in the broadest sense—power active and power passive; power to do and power to endure; power to exert force and power to resist it.

If he goes further and analyzes the reasons for this impression of power, he will see that it is not merely a mental suggestion, but a realization of the actual existence of tremendous mechanical power, under complete direction and control.

In mechanics we get a definition of power, which, like all definitions in mechanics, is clear, definite, and correct. In mechanics, power is the rate at which mechanical work is performed. It is ability to do something in a certain definite time.

Now this definition gives us a clear idea of the way in which a navy directly represents power, because the power which a navy exerts is, primarily, mechanical; and any other power which it exerts is secondary and derived wholly from its mechanical power. The power of a gun is due wholly to the mechanical energy of its projectile, which enables it to penetrate a resisting body; and the power of a moving ship is due wholly to the mechanical energy of the burning coal within its furnaces.

It may be objected that it is not reasonable to consider a ship's energy of motion as an element of naval power, in the mechanical sense in which we have been using the word "power," for the reason that it could be exerted only by the use of her ram, an infrequent use. To this it may be answered that energy is energy, no matter to what purpose it is applied; that a given projectile going at a given speed has a certain energy, whether it strikes its target or misses it; and that a battleship going at a certain speed must necessarily have a certain definite energy, no matter whether it is devoted to ramming another ship or to carrying itself and its contents from one place to another.

Besides the mechanical power exerted by the mere motion of the ship, and often superior to it, there is the power of her guns and torpedoes.

Perhaps the most important single invention ever made was the invention of gunpowder. Why? Because it put into the hands of man a tremendous force, compressed into a very small volume, which he could use instantaneously or refrain from using at his will. Its first use was in war; and in war has been its main employment ever since. War gives the best field for the activity of gunpowder, because in war, we always wish to exert a great force at a definite point at a given instant; usually in order to penetrate the bodies of men, or some defensive work that protects them. Gunpowder is the principal agent used in war up to the present date. It is used by both armies and navies, but navies use it in larger masses, fired in more powerful guns.

Of course this does not mean that it would be impossible to send a lot of powder to a fort, more than a fleet could carry, and fire it; but it does mean that history shows that forts have rarely been called upon to fire much powder, that their lives have been serene, and that most of the powder fired on shore has been fired by infantry using muskets—though a good deal has been fired by field and siege artillery.

Leaving forts out of consideration and searching for something else in which to use gunpowder on a large scale, we come to siege-pieces, field-pieces, and muskets. Disregarding siege-pieces and field-pieces, for the reason that the great variety of types makes it difficult to compare them with navy guns, we come to muskets.

Now the musket is an extremely formidable weapon, and has, perhaps, been the greatest single contributor to the victory of civilization over barbarism, and order over anarchy, that has ever existed up to the present time. But the enormous advances in engineering, including ordnance, during the last fifty years, have reduced enormously the relative value of the musket. Remembering that energy, or the ability to do work, is expressed by the formula: E=1/2 MV2, remembering that the projectile of the modern 12-inch gun starts at about 2,900 f. s. velocity and weighs 867 pounds, while the bullet of a musket weighs only 150 grains and starts with a velocity of 2,700 feet per second, we see that the energy of the 12-inch projectile is about 47,000 times that of the bullet on leaving the muzzle. But after the bullet has gone, say 5,000 yards, its energy has fallen to zero, while the energy of the 12-inch projectile is nearly the same as when it started.

While it would be truthful, therefore, to say that the energy of the 12-inch gun within 5,000 yards is greater than that of 47,000 muskets, it would also be truthful to say that outside of 5,000 yards, millions of muskets would not be equal to one 12-inch gun.

Not only is the 12-inch gun a weapon incomparably great, compared with the musket, but when placed in a naval ship, it possesses a portability which, while not an attribute of the gun itself, is an attribute of the combination of gun and ship, and a distinct attribute of naval power. A 12-inch gun placed in a fort may be just as good as a like gun placed in a ship, but it has no power to exert its power usefully unless some enemy comes where the gun can hit it. And when one searches the annals of history for the records of whatever fighting forts have done, he finds that they have been able to do very little. But a 12-inch gun placed in a man-of-war can be taken where it is needed, and recent history shows that naval 12-inch guns, modern though they are, have already done effective work in war.

Not only are 12-inch guns powerful and portable, but modern mechanical science has succeeded in so placing them in our ships that they can be handled with a precision, quickness, and delicacy that have no superior in any other branch of engineering. While granting the difficulty of an exact comparison, I feel no hesitation in affirming that the greatest triumph of the engineering art in handling heavy masses is to be found in the turret of a battleship. Here again, and even inside of 5,000 yards, we find the superiority of the great gun over the musket, as evidenced by its accuracy in use. No soldier can fire his musket, even on a steady platform, himself and target stationary, and the range known perfectly, as accurately as a gun-pointer can fire a 12-inch gun; and if gun and target be moving, and the wind be blowing, and the range only approximately known, as is always the case in practice, the advantage of the big gun in accuracy becomes incomparable.

But it is not only the big projectile itself which has energy, for this projectile carries a large charge of high explosive, which exploding some miles away from where it started, exerts a power inherent in itself, that was exhibited with frightful effect at the battles of Tsushima and the Skagerak.

This brings us to the auto-torpedo, a weapon recently perfected; in fact not perfected yet. Here is another power that science has put into the hands of naval men in addition to those she had already put there. The auto-torpedo, launched in security from below the water-line of the battleship, or from a destroyer or submarine, can be directed in a straight line over a distance and with a speed that are constantly increasing with the improvement of the weapon. At the present moment, a speed of 27 knots over 10,000 yards can be depended on, with a probability that on striking an enemy's ship below the water-line it will disable that ship, if not sink her. There seems no doubt that, in a very few years, the systematic experiments now being applied to the development of the torpedo will result in a weapon which can hardly be called inferior to the 12-inch or even 16-inch gun and will probably surpass it.

Controllability.—If one watches a fleet of ships moving on the sea, he gets an impression of tremendous power. But if he watches Niagara, or a thunder-storm, he also gets an impression of tremendous power. But the tremendous power of Niagara, or the thunder-storm, is a power that belongs to Niagara or the thunder-storm, and not to man. Man cannot control the power of Niagara or the thunder-storm; but he can control the power of a fleet.

Speaking, then, from the standpoint of the human being, one may say that the fleet has the element of controllability, while Niagara and the thunder-storm have not. One man can make the fleet go faster or slower or stop; he can increase its power of motion or decrease it at his will; he can reduce it to zero. He cannot do so with the forces of nature.

Directability.—Not only can one man control the power of the fleet, he can also direct it; that is, can turn it to the right or the left as much as he wishes. But one man cannot change the direction of motion of Niagara or the lightning-bolt.

Power, Controllability, and Directability.—We may say, then, that a fleet combines the three elements of mechanical power, controllability, and directability.

The Unit of Military Power.—This is an enormous power that has come into the hands of the naval nations; but it has come so newly that we do not appreciate it yet. One reason why we do not and cannot appreciate it correctly is that no units have been established by which to measure it.

To supply this deficiency, the author begs leave to point out that, since the military power of every nation has until recently been its army, of which the unit has been the soldier, whose power has rested wholly in his musket, the musket has actually been the unit of military power. In all history, the statement of the number of men in each army has been put forward by historians as giving the most accurate idea of their fighting value; and in modern times, nearly all of these men have been armed with muskets only.

It has been said already that the main reason why the invention of gunpowder was so important was that it put into the hands of man a tremendous mechanical power compressed into a very small space, which man could use or not use at his will. This idea may be expressed by saying that gunpowder combines power and great controllability. But it was soon discovered that this gunpowder, put into a tube with a bullet in front of it, could discharge that bullet in any given direction. A musket was the result, and it combined the three requisites of a weapon—mechanical power, controllability, and directability.

While the loaded gun is perhaps the clearest example of the combination of the three factors we are speaking of, the moving ship supplies the next best example. It has very much greater mechanical power; and in proportion to its mass, almost as much controllability and directability.

The control and direction of a moving ship are very wonderful things; but the very ease with which they are exercised makes us overlook the magnitude of the achievement and the perfection of the means employed. It may seem absurd to speak of one man controlling and directing a great ship, but that is pretty nearly what happens sometimes; for sometimes the man at the wheel is the only man on board doing anything at all; and he is absolutely directing the entire ship. At such times (doubtless they are rare and short) the man at the wheel on board, say the Vaterland, is directing unassisted by any human being a mass of 65,000 tons, which is going through the water at a speed of 24 knots, or 27 miles, an hour, nearly as fast as the average passenger-train. In fact, it would be very easy to arrange on board the Vaterland that this should actually happen; that everybody should take a rest for a few minutes, coal-passers, water-tenders, oilers, engineers, and the people on deck. And while such an act might have no particular value, per se, and prove nothing important, yet, nevertheless, a brief reflection on the possibility may be interesting, and lead us to see clearly into the essential nature of what is here called "directability." The man at the wheel on board the Vaterland, so long as the fires burn and the oil continues to lubricate the engines, has a power in his hands that is almost inconceivable. The ship that he is handling weighs more than the 870,000 men that comprise the standing army of Germany.