THE HOLY FAMILY.

Project Gutenberg's St. Nicholas, Vol. 5, No. 2, December, 1877, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: St. Nicholas, Vol. 5, No. 2, December, 1877 Author: Various Release Date: March 15, 2005 [EBook #15373] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ST. NICHOLAS, VOL. 5, NO. 2, *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Lynn Bornath and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net.

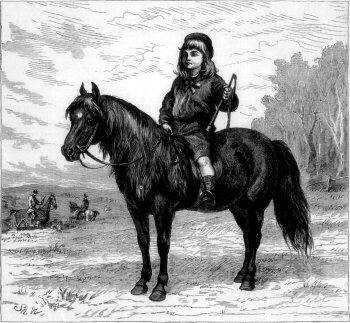

[The following hitherto-unprinted fragment by Theodore Winthrop, author of "John Brent," "The Canoe and the Saddle," "Life in the Open Air," and other works, was intended by him for the first chapter of a story called "Steers Flotsam," but it has an interest of its own, and is a complete narrative in itself.

Perhaps there are many of our young readers who do not know the history of that brave young officer who, one of the very first to fall in the late war, was killed at Great Bethel, Virginia, June 10, 1861. He was born at New Haven, Connecticut, in September, 1828. He was a studious and quiet boy, and not very robust. From early youth he had determined to become an author worthy of fame, but he tore himself away from his beloved work at the call of his country just as he was about to win that fame, leaving behind him a number of finished and unfinished writings, most of which were afterward published.

He could handle oars as well as write of them, could skate like his hero in "Love and Skates," and was good at all manly sports. He traveled much, visited Europe twice, lived two years at the Isthmus of Panama, and returning from there across the plains (an adventurous trip at that time), learned in those far western wilds to manage and understand the half-tamed horses and untamed savages about whom he writes so well. This varied experience gave a freedom and power to his pen that the readers of the ST. NICHOLAS are not too young to perceive and appreciate.]

Almost sunset. I pulled my boat's head round, and made for home.

I had been floating with the tide, drifting athwart the long shadows under the western bank, shooting across the whirls and eddies of the rapid strait, grappling to one and another of the good-natured sloops and schooners that swept along the highway to the great city, near at hand.

For an hour I had sailed over the fleet, smooth glimmering water, free and careless as a sea-gull. Now I must 'bout ship and tussle with the whole force of the tide at the jaws of Hellgate. I did not know that not for that day only, but for life, my floating gayly with the stream was done.

I pulled in under the eastern shore, and began to give way with all my boyish force.

I was a little fellow, only ten years old, but my pretty white skiff was little, in proportion, and so were my sculls, and we were all used to work together.

As I faced about, a carriage came driving furiously along the turn of the shore. The road followed the water's edge. I was pulling close to the rocks to profit by every eddy. The carriage whirled by so near me that I could recognize one of the two persons within. No mistaking that pale, keen face. He evidently saw and recognized me also. He looked out at the window and signaled the coachman to stop. But before the horses could be pulled into a trot he gave a sign to go on again. The carriage disappeared at a turn of the shore.

This encounter strangely dispirited me. My joy in battling with the tide, in winning upward, foot by foot, boat's length after boat's length, gave place to a forlorn doubt whether I could hold my own—whether I should not presently be swept away.

The tide seemed to run more sternly than I had ever known it. It made a plaything of my little vessel, slapping it about most uncivilly. The black rocks, covered with clammy, unwholesome-looking sea-weed, seemed like the mile-stones of a nightmare, steadily to move with me. The water, bronzed by the low sun, poured mightily along, and there hung my boat, glued to its white reflection.

As I struggled there, the great sloops and schooners rustling by with the ebb, and eclipsing an instant the June sunset, gave me a miserable impression of careless unfriendliness. I had made friends with them all my life, and this evening, while I was drifting down-stream, they had been willing enough to give me a tow, and to send bluff, good-humored replies to my boyish hails. Now they rushed on, each chasing the golden wake of its forerunner, and took no thought of me, straining at my oar, apart. I grew dispirited, quite to the point of a childish despair.

Of course it was easy enough to land, leave my boat, and trudge home, but that was a confession of defeat not to be thought of. Two things only my father required of me—manliness and truth. My pretty little skiff—the "Aladdin," I called it—he had given to me as a test of my manhood. I should be ashamed of myself to go home and tell him that I had abdicated my royal prerogative of taking care of myself, and pulling where I would in a boat with a keel. I must take the "Aladdin" home, or be degraded to my old punt, and confined to still water.

The alternative brought back strength to my arms. I threw off the ominous influence. I leaned to my sculls. The clammy black rocks began deliberately to march by me down-stream. I was making headway, and the more way I made, the more my courage grew.

Presently, as I battled round a point, I heard a rustle and a rush of something coming, and the bowsprit of a large sloop glided into view close by me. She was painted in stripes of all colors above her green bottom. The shimmer of the water shook the reflection of her hull, and made the edges of the stripes blend together. It was as if a rainbow had suddenly flung itself down for me to sail over.

I looked up and read the name on her headboards, "James Silt."

At the same moment a child's voice over my head cried, "Oh, brother Charles! what a little boy! what a pretty boat!"

The gliding sloop brought the speaker into view. She was a girl both little and pretty. A rosy, blue-eyed, golden-haired sprite, hanging over the gunwale, and smiling pleasantly at me.

"Yes, Betty," the voice of a cheerful, honest-looking young fellow at the tiller—evidently brother Charles—replied. "He's a little chap, but he's got a man into him. Hurrah!"

"Give way, 'Aladdin!' Stick to it! You're sure to get there."

The sloop had slid along by me now, so that I could read her name repeated on her stern—"James Silt, New Haven."

"Good-bye, little boy!" cried my cherubic vision to me, flitting aft, and leaning over the port davit.

"Good-bye, sissy!" I returned, and raising my voice, I hailed, "Good-bye, Cap'n Silt!"

Brother Charles looked puzzled an instant. Then he gave a laugh, and shouted across the broadening interval of burnished water, "You got my name off the stern. Well, it's right, and you're a bright one. You'll make a sailor! Good luck to you!"

He waved his cap, and the strong tide swept his craft onward, dragging her rainbow image with her.

As far as I could see, the fair-haired child was leaning over the stern watching me, and brother Charles, at intervals, turned and waved his cap encouragingly.

This little incident quite made a man of me again. I forgot the hard face I had seen, and brother Charles's frank, merry face took its place, while, leaning over brother Charles's shoulder, was that angelic vision of his sister.

Under the inspiring influence of Miss Betty's smiles—a boy is never so young as not to conduct such electricity—I pulled along at double speed. I no longer measured my progress by the rocks in the mud, but by the cottages and villas on the bank. Now that I had found friends on board one of the vessels arrowing by, it seemed as if all would prove freighted with sympathizing people if they would only come near enough to hail. But I was content with the two pleasant faces stamped on my memory, and only minded my business of getting home before dark.

The setting sun drew itself a crimson path across the widening strait. The smooth water grew all deliciously rosy with twilight. The moon had just begun to put in a faint claim to be recognized as a luminary, when I pulled up to my father's private jetty.

Everything looked singularly sweet and quiet. June never, in all her dreams of perfection, could have devised a fairer evening. I was a little disappointed to miss my father from his usual station on the wharf. He loved to be there to welcome me returning from my little voyages, and to hail me gently: "Now then, Harry, a strong pull, and let me see how far you can send her! Bravo, my boy! We'll soon make a man of you. You shall not be a weakling all your life as your father has been, mind and body, for want of good strong machinery to work with."

He was absent that evening. I hurried to bestow my boat neatly in the boat-house. I locked the door, pocketed the key, and ran up the lawn, thinking how pleased my father would be to hear of my adventure with the sloop and its crew, and how he would make me sketch the sloop for him, which I could do very fairly, and how he would laugh at my vain attempts to convey to him the cheeks and the curls of Miss Betty.

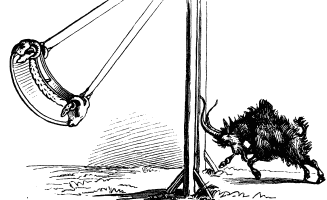

"I'LL BUTT IT," SAID THE GOAT. |

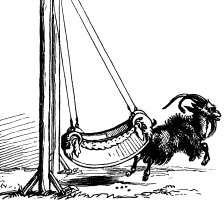

"WHAT! IT BUTTS AGAIN." |

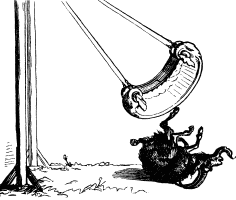

"I'LL GIVE IT A GOOD ONE, THIS TIME." |

|

"PERHAPS I'D BETTER GET OUT OF ITS WAY." |

BUT HE DIDN'T. |

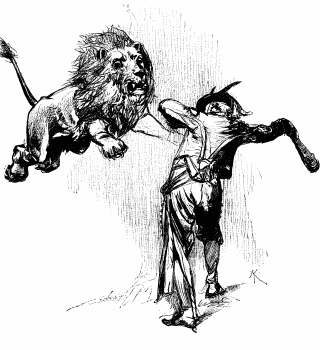

eople in Tunis, Africa,—at least, some of the older people,—often talk of the wonderful exploits of a lion-killer who was famous there forty years ago. The story is this, and is said to be entirely true:

The lion-killer was called "The Sicilian," because his native country was Sicily; and he was known as "The Christian" among the people in Tunis, who were mostly Arabs, and, consequently, Mohammedans. He was also called "Hercules," because of his strength,—that being the name of a strong demi-god of the ancient Greeks. He was not built like Hercules, however; he was tall, but beautifully proportioned, and there was nothing in his form that betrayed his powerful muscles. He performed prodigies of strength with so much gracefulness and ease as to astonish all who saw them.

He was a member of a traveling show company that visited Tunis,—very much as menagerie and circus troupes go about this country now from town to town. His part of the business was, not simply to do things that would display his great strength, but also to represent scenes by pantomime so that they would appear to the audience exactly as if the real scenes were being performed before their very eyes. In one of these scenes he showed the people how he had encountered and killed a lion with a wooden club in the country of Damascus. This is the manner in which he did it:

After a flourish of trumpets, the Sicilian came upon the stage, which was arranged to represent a circle, or arena, and had three palm-trees in the middle. He was handsomely dressed in a costume of black velvet, trimmed with silver braid, and, as he looked around upon the audience with a grave but gentle expression, and went through with the Arabian salutation, which was to bear his right hand to his heart, mouth and forehead successively, there was perfect silence, so charmed were the people with his beauty and dignity.

Then an interpreter cried:

"The Christian will show you how, with his club, he killed a lion in the country of Damascus!"

Immediately following this came another flourish of trumpets and a striking of cymbals, as if to announce the entrance of the lion. Quickly the Sicilian sprang behind one of the three palms, whence to watch his enemy. With an attentive and resolute eye, leaning his body first to the right, and then to the left, of the tree, he kept his gaze on the terrible beast, following all its movements with the graceful motions of his own body, so naturally and suitably as to captivate the attention of the spectators.

"The lion surely is there!" they whispered. "We do not see him, but he sees him! How he watches his least motion! How resolute he is! He will not allow himself to be surprised——"

Suddenly the Sicilian leaps; with a bound he has crossed from one palm-tree to another, and, with a second spring, has climbed half-way up the tree, still holding his massive club in one hand. One understands by his movements that the lion has followed him, and, crouched and angry, stops at the foot of the tree. The Sicilian, leaning over, notes the slightest change of posture; then, like a flash of light, he leaps to the ground behind the trunk of the tree; the terrible club makes a whistling sound as it swings through the air, and the lion falls to the ground.

The scene was so well played that the wildest applause came from all parts of the audience.

Then the interpreter came in, and, throwing at the feet of the Hercules a magnificent lion's skin, cried:

"Behold the skin of the lion that the Christian killed in the country of Damascus."

The fame of the Sicilian reached the ears of the Bey of Tunis. But the royal dignity of the Bey, the reigning prince of that country, would not allow him to be present at exhibitions given to the common people. Finally, however, having heard so much about the handsome and strong Sicilian, he became curious to see him, and said:

"If this Christian has killed one lion with a club, he can kill another. Tell him that if he will knock down my grand lion with it, I will give him a thousand ducats"—quite a large sum in those days, a ducat being about equal to the American dollar.

At this time the Bey had several young lions that ran freely about in the court-yard or garden of his palace, and in a great pit, entirely surrounded by a high terrace, on a level with the ground-floor of the palace, a superb Atlas lion was kept in royal captivity. It was this lion that the Bey wished the Sicilian to combat. The proposition was sent to the Sicilian, who accepted it without hesitation, and without boasting what he would do.

The combat was to take place a week from that time, and the announcement that the handsome Sicilian was to fight a duel with the grand lion was spread far and wide, even to the borders of the desert, producing a profound sensation. Everybody, old and young, great and small, desired to be present; moreover, the people would be freely admitted to the garden of the Bey, where they could witness the combat from the top of the terrace. The duel was to be early in the morning, before the heat of the day.

During the week that intervened, the Sicilian performed every day in the show, instead of two days a week, as had been his custom. Never was he more calm, graceful and fascinating in his performances. The evening before the eventful day, he repeated in pantomime his victory over the lion near Damascus, with so much elegance, precision and suppleness as to elicit round after round of enthusiastic cheers. Of course everybody who had seen him play killing a lion was wild with curiosity to see him actually fight with a real lion.

So, on the following morning, in the early dawn, the terrace around the lion's pit was crowded with people. For three days the grand lion had been deprived of food in order that he might be the more ferocious and terrible. His eyes shone like two balls of fire, and he incessantly lashed his flanks with his tail. At one moment he would madly roar, and, in the next, rub himself against the wall, vainly trying to find a chink between the stones in which to insert his claws.

Precisely at the appointed hour, the princely Bey and his court took the places that had been reserved for them on one side of the terrace. The Sicilian came a few steps behind, dressed in his costume of velvet and silver, and holding his club in his hand. With his accustomed easy and regular step, and a naturally elegant and dignified bearing, he advanced in front of the royal party and made a low obeisance to the Bey. The prince made some remark to him, to which he responded with a fresh salute; then he withdrew, and descended the steps which led to the lion's pit.

The crowd was silent. At the end of some seconds, the barred gate of the pit was opened, and gave entrance, not to the brave and powerful Hercules, but to a poor dog that was thrown toward the ferocious beast with the intention of still more exciting its ravenous appetite. This unexpected act of cruelty drew hisses from the spectators, but they were soon absorbed in watching the behavior of the dog. When the lion saw the prey that had been thrown to him, he stood motionless for a moment, ceased to beat his flanks with his tail, growled deeply, and crouched on the ground, with his paws extended, his neck stretched out, and his eyes fixed upon the victim.

The dog, on being thrown into the pit, ran at once toward a corner of the wall, as far as possible from the lion, and, trembling, yet not overcome by fear, fixed his eyes on the huge beast, watching anxiously, but intently, his every motion.

With apparent unconcern, the lion creepingly advanced toward the dog, and then, with a sudden movement, he was upon his feet, and in a second launched himself into the air! But the dog that same instant bounded in an opposite direction, so that the lion fell in the corner, while the dog alighted where the lion had been.

For a moment the lion seemed very much surprised at the loss of his prey; with the dog, the instinct of self-preservation developed a coolness that even overcame his terror. The body of the poor animal was all in a shiver, but his head was firm, his eyes were watchful. Without losing sight of his enemy, he slowly retreated into the corner behind him.

Then the lion, scanning his victim from the corners of his eyes, walked sidewise a few steps, and, turning suddenly, tried again to pounce with one bound upon the dog; but the latter seemed to anticipate this movement also, and, in the same second, jumped in the opposite direction, as before, crossing the lion in the air.

At this the lion became furious, and lost the calmness that might have insured him victory, while the courage of the unfortunate dog won for him the sympathy of all the spectators.

As the lion, excited and terrible, was preparing a new plan of attack, a rope ending in a loop was lowered to the dog. The brave little animal, whose imploring looks had been pitiful to look upon, saw the help sent to him, and, fastening his teeth and claws into the rope, was immediately drawn up. The lion, perceiving this, made a prodigious leap, but the dog was happily beyond his reach. The poor creature, drawn in safety to the terrace, at once took flight, and was soon lost to view.

At the moment when the lion threw himself on the ground of the pit, roaring with rage at the escape of his prey, the Sicilian entered, calm and firm, superb in his brilliant costume, and with his club in his hand.

At his appearance in the pit, a silence like death came over the crowd of spectators. The Hercules walked rapidly toward a corner, and, leaning upon his club, awaited the onslaught of the lion, who, blinded by fury, had not yet perceived his entrance.

The waiting was of short duration, for the lion, in turning, espied him, and the fire that flashed from the eyes of the terrible beast told of savage joy in finding another victim.

Here, however, the animal showed for a moment a feeling of anxiety; slowly, as if conscious that he was in the presence of a powerful adversary, he retreated some steps, keeping his fiery eyes all the time on the man. The Sicilian also kept his keen gaze on the lion, and, with his body slightly inclined forward, marked every alteration of position. Between the two adversaries, it was easy to see that fear was on the side of the beast; but, in comparing the feeble means of the man—a rude club—with the powerful structure of the lion, whose boundings made the very ground beneath him tremble, it was hard for the spectators to believe that courage, and not strength, would win the victory.

The lion was too excited and famished to remain long undecided. After more backward steps, which he made as if gaining time for reflection, he suddenly advanced in a sidelong direction in order to charge upon his adversary.

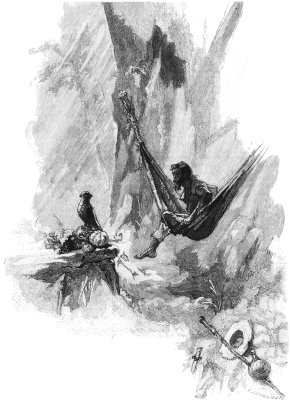

"THE BEAST GAVE A MIGHTY SPRING."

The Sicilian did not move, but followed with his fixed gaze the motions of the lion. Greatly irritated, the beast gave a mighty spring, uttering a terrible roar; the man, at the same moment, leaped aside, and the lion had barely touched the ground, when the club came down upon his head with a dull, shocking thud. The king of the desert rolled heavily under the stroke, and fell headlong, stunned and senseless, but not dead.

The spectators, overcome with admiration, and awed at the exhibition of so much calmness, address and strength, were hushed into profound silence. The next moment, the Bey arose, and, with a gesture of his hand, asked mercy for his favorite lion.

"A thousand ducats the more if you will not kill him!" he cried to the Sicilian. "Agreed!" was the instant reply.

The lion lay panting on the ground. The Hercules bowed at the word of the Bey, and slowly withdrew, still keeping his eyes on the conquered brute. The two thousand ducats were counted out and paid. The lion shortly recovered.

With a universal gasp of relief, followed by deafening shouts and cheers, the spectators withdrew from the terrace, having witnessed a scene they could never forget, and which, as I said at the beginning, is still talked of in Tunis.

It was a very hot afternoon,—too hot to go for a walk or do anything,—or else it wouldn't have happened, I believe.

In the first place, I want to know why fairies should always be teaching us to do our duty, and lecturing us when we go wrong, and we should never teach them anything? You can't mean to say that fairies are never greedy, or selfish, or cross, or deceitful, because that would be nonsense, you know. Well, then, don't you agree with me that they might be all the better for a little scolding and punishing now and then?

I really don't see why it shouldn't be tried, and I'm almost sure (only please don't repeat this loud in the woods) that if you could only catch a fairy, and put it in the corner, and give it nothing but bread and water for a day or two, you'd find it quite an improved character; it would take down its conceit a little, at all events.

The next question is, what is the best time for seeing fairies? I believe I can tell you all about that.

The first rule is, that it must be a very hot day—that we may consider as settled; and you must be just a little sleepy—but not too sleepy to keep your eyes open, mind. Well, and you ought to feel a little—what one may call "fairyish"—the Scotch call it "eerie," and perhaps that's a prettier word; if you don't know what it means, I'm afraid I can hardly explain it; you must wait till you meet a fairy, and then you'll know.

And the last rule is, that the crickets shouldn't be chirping. I can't stop to explain that rule just now—you must take it on trust for the present.

So, if all these things happen together, you've a good chance of seeing a fairy—or at least a much better chance than if they didn't.

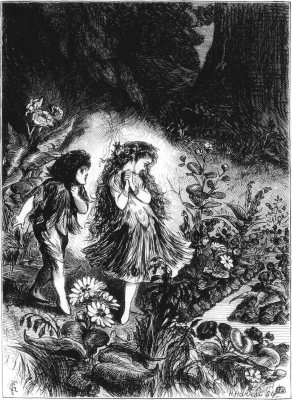

The one I'm going to tell you about was a real, naughty little fairy. Properly speaking, there were two of them, and one was naughty and one was good, but perhaps you would have found that out for yourself.

Now we really are going to begin the story.

It was Tuesday afternoon, about half-past three,—it's always best to be particular as to dates,—and I had wandered down into the wood by the lake, partly because I had nothing to do, and that seemed to be a good place to do it in, and partly (as I said at first) because it was too hot to be comfortable anywhere, except under trees.

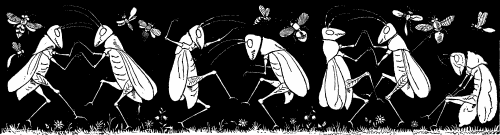

The first thing I noticed, as I went lazily along through an open place in the wood, was a large beetle lying struggling on its back, and I went down directly on one knee to help the poor thing on its feet again. In some things, you know, you can't be quite sure what an insect would like; for instance, I never could quite settle, supposing I were a moth, whether I would rather be kept out of the candle, or be allowed to fly straight in and get burnt; or, again, supposing I were a spider, I'm not sure if I should be quite pleased to have my web torn down, and the fly let loose; but I feel quite certain that, if I were a beetle and had rolled over on my back, I should always be glad to be helped up again.

So, as I was saying, I had gone down on one knee, and was just reaching out a little stick to turn the beetle over, when I saw a sight that made me draw back hastily and hold my breath, for fear of making any noise and frightening the little creature away.

Not that she looked as if she would be easily frightened; she seemed so good and gentle that I'm sure she would never expect that any one could wish to hurt her. She was only a few inches high, and was dressed in green, so that you really would hardly have noticed her among the long grass; and she was so delicate and graceful that she quite seemed to belong to the place, almost as if she were one of the flowers. I may tell you, besides, that she had no wings (I don't believe in fairies with wings), and that she had quantities of long brown hair and large, earnest brown eyes, and then I shall have done all I can to give you an idea of what she was like.

Sylvie (I found out her name afterward) had knelt down, just as I was doing, to help the beetle; but it needed more than a little stick for her to get it on its legs again; it was as much as she could do, with both arms, to roll the heavy thing over; and all the while she was talking to it, half-scolding and half-comforting, as a nurse might do with a child that had fallen down.

"There, there! You needn't cry so much about it; you're not killed yet—though if you were, you couldn't cry, you know, and so it's a general rule against crying, my dear! And how did you come to tumble over? But I can see well enough how it was,—I needn't ask you that,—walking over sand-pits with your chin in the air, as usual. Of course if you go among sand-pits like that, you must expect to tumble; you should look."

The beetle murmured something that sounded like "I did look," and Sylvie went on again:

"But I know you didn't! You never do! You always walk with your chin up—you're so dreadfully conceited. Well, let's see how many legs are broken this time. Why, none of them, I declare! though that's certainly more than you deserve. And what's the good of having six legs, my dear, if you can only kick them all about in the air when you tumble? Legs are meant to walk with, you know. Now, don't be cross about it, and don't begin putting out your wings yet; I've some more to say. Go down to the frog that lives behind that buttercup—give him my compliments—Sylvie's compliments—can you say 'compliments?'"

The beetle tried, and, I suppose, succeeded.

"Yes, that's right. And tell him he's to give you some of that salve I left with him yesterday. And you'd better get him to rub it in for you; he's got rather cold hands, but you mustn't mind that."

I think the beetle must have shuddered at this idea, for Sylvie went on in a graver tone:

"Now, you needn't pretend to be so particular as all that, as if you were too grand to be rubbed by a frog. The fact is, you ought to be very much obliged to him. Suppose you could get nobody but a toad to do it, how would you like that?"

There was a little pause, and then Sylvie added:

"Now you may go. Be a good beetle, and don't keep your chin in the air."

And then began one of those performances of humming, and whizzing, and restless banging about, such as a beetle indulges in when it has decided on flying, but hasn't quite made up its mind which way to go. At last, in one of its awkward zigzags, it managed to fly right into my face, and by the time I had recovered from the shock, the little fairy was gone.

I looked about in all directions for the little creature, but there was no trace of her—and my "eerie" feeling was quite gone off, and the crickets were chirping again merrily, so I knew she was really gone.

And now I've got time to tell you the rule about the crickets. They always leave off chirping when a fairy goes by, because a fairy's a kind of queen over them, I suppose; at all events, it's a much grander thing than a cricket; so whenever you're walking out, and the crickets suddenly leave off chirping, you may be sure that either they see a fairy, or else they're frightened at your coming so near.

I walked on sadly enough, you may be sure. However, I comforted myself with thinking, "It's been a very wonderful afternoon, so far; I'll just go quietly on and look about me, and I shouldn't wonder if I come across another fairy somewhere."

Peering about in this way, I happened to notice a plant with rounded leaves, and with queer little holes cut out in the middle of several of them. "Ah! the leaf-cutter bee," I carelessly remarked; you know I am very learned in natural history (for instance, I can always tell kittens from chickens at one glance); and I was passing on, when a sudden thought made me stoop down and examine the leaves more carefully.

Then a little thrill of delight ran through me, for I noticed that the holes were all arranged so as to form letters; there were three leaves side by side, with "B," "R" and "U" marked on them, and after some search I found two more, which contained an "N" and an "O."

By this time the "eerie" feeling had all come back again, and I suddenly observed that no crickets were chirping; so I felt quite sure that "Bruno" was a fairy, and that he was somewhere very near.

And so indeed he was—so near that I had very nearly walked over him without seeing him; which would have been dreadful, always supposing that fairies can be walked over; my own belief is that they are something of the nature of will-o'-the-wisps, and there's no walking over them.

Think of any pretty little boy you know, rather fat, with rosy cheeks, large dark eyes, and tangled brown hair, and then fancy him made small enough to go comfortably into a coffee-cup, and you'll have a very fair idea of what the little creature was like.

"What's your name, little fellow?" I began, in as soft a voice as I could manage. And, by the way, that's another of the curious things in life that I never could quite understand—why we always begin by asking little children their names; is it because we fancy there isn't quite enough of them, and a name will help to make them a little bigger? You never thought of asking a real large man his name, now, did you? But, however that may be, I felt it quite necessary to know his name; so, as he didn't answer my question, I asked it again a little louder. "What's your name, my little man?"

"What's yours?" he said, without looking up.

"My name's Lewis Carroll," I said, quite gently, for he was much too small to be angry with for answering so uncivilly.

"Duke of Anything?" he asked, just looking at me for a moment, and then going on with his work.

"Not Duke at all," I said, a little ashamed of having to confess it.

"You're big enough to be two Dukes," said the little creature. "I suppose you're Sir Something, then?"

"No," I said, feeling more and more ashamed. "I haven't got any title."

The fairy seemed to think that in that case I really wasn't worth the trouble of talking to, for he quietly went on digging, and tearing the flowers to pieces as fast as he got them out of the ground. After a few minutes I tried again:

"Please tell me what your name is."

"Bruno," the little fellow answered, very readily. "Why didn't you say 'please' before?"

"That's something like what we used to be taught in the nursery," I thought to myself, looking back through the long years (about a hundred and fifty of them) to the time when I used to be a little child myself. And here an idea came into my head, and I asked him, "Aren't you one of the fairies that teach children to be good?"

"Well, we have to do that sometimes," said Bruno, "and a dreadful bother it is."

As he said this, he savagely tore a heart's-ease in two, and trampled on the pieces.

"What are you doing there, Bruno?" I said.

"Spoiling Sylvie's garden," was all the answer Bruno would give at first. But, as he went on tearing up the flowers, he muttered to himself, "The nasty c'oss thing—wouldn't let me go and play this morning, though I wanted to ever so much—said I must finish my lessons first—lessons, indeed! I'll vex her finely, though!"

"Oh, Bruno, you shouldn't do that!" I cried. "Don't you know that's revenge? And revenge is a wicked, cruel, dangerous thing!"

"River-edge?" said Bruno. "What a funny word! I suppose you call it cooel and dangerous because, if you went too far and tumbled in, you'd get d'owned."

"No, not river-edge," I explained; "rev-enge" (saying the word very slowly and distinctly). But I couldn't help thinking that Bruno's explanation did very well for either word.

"Oh!" said Bruno, opening his eyes very wide, but without attempting to repeat the word.

"Come! try and pronounce it, Bruno!" I said, cheerfully. "Rev-enge, rev-enge."

But Bruno only tossed his little head, and said he couldn't; that his mouth wasn't the right shape for words of that kind. And the more I laughed, the more sulky the little fellow got about it.

"Well, never mind, little man!" I said. "Shall I help you with the job you've got there?"

"Yes, please," Bruno said, quite pacified. "Only I wish I could think of something to vex her more than this. You don't know how hard it is to make her ang'y!"

"Now listen to me, Bruno, and I'll teach you quite a splendid kind of revenge!"

"Something that'll vex her finely?" Bruno asked with gleaming eyes.

"Something that'll vex her finely. First, we'll get up all the weeds in her garden. See, there are a good many at this end—quite hiding the flowers."

"But that wont vex her," said Bruno, looking rather puzzled.

"After that," I said, without noticing the remark, "we'll water the highest bed—up here. You see it's getting quite dry and dusty."

Bruno looked at me inquisitively, but he said nothing this time.

"Then, after that," I went on, "the walks want sweeping a bit; and I think you might cut down that tall nettle; it's so close to the garden that it's quite in the way—"

"What are you talking about?" Bruno impatiently interrupted me. "All that wont vex her a bit!"

"Wont it?" I said, innocently. "Then, after that, suppose we put in some of these colored pebbles—just to mark the divisions between the different kinds of flowers, you know. That'll have a very pretty effect."

Bruno turned round and had another good stare at me. At last there came an odd little twinkle in his eye, and he said, with quite a new meaning in his voice:

"V'y well—let's put 'em in rows—all the 'ed together, and all the blue together."

"That'll do capitally," I said; "and then—what kind of flowers does Sylvie like best in her garden?"

Bruno had to put his thumb in his mouth and consider a little before he could answer. "Violets," he said, at last.

"There's a beautiful bed of violets down by the lake—"

"Oh, let's fetch 'em!" cried Bruno, giving a little skip into the air. "Here! Catch hold of my hand, and I'll help you along. The g'ass is rather thick down that way."

I couldn't help laughing at his having so entirely forgotten what a big creature he was talking to.

"No, not yet, Bruno," I said; "we must consider what's the right thing to do first. You see we've got quite a business before us."

"Yes, let's consider," said Bruno, putting his thumb into his mouth again, and sitting down upon a stuffed mouse.

"What do you keep that mouse for?" I said. "You should bury it, or throw it into the lake."

"Why, it's to measure with!" cried Bruno. "How ever would you do a garden without one? We make each bed th'ee mouses and a half long, and two mouses wide."

I stopped him, as he was dragging it off by the tail to show me how it was used, for I was half afraid the "eerie" feeling might go off before we had finished the garden, and in that case I should see no more of him or Sylvie.

"I think the best way will be for you to weed the beds, while I sort out these pebbles, ready to mark the walks with."

"That's it!" cried Bruno. "And I'll tell you about the caterpillars while we work."

"Ah, let's hear about the caterpillars," I said, as I drew the pebbles together into a heap, and began dividing them into colors.

And Bruno went on in a low, rapid tone, more as if he were talking to himself. "Yesterday I saw two little caterpillars, when I was sitting by the brook, just where you go into the wood. They were quite g'een, and they had yellow eyes, and they didn't see me. And one of them had got a moth's wing to carry—a g'eat b'own moth's wing, you know, all d'y, with feathers. So he couldn't want it to eat, I should think—perhaps he meant to make a cloak for the winter?"

"Perhaps," I said, for Bruno had twisted up the last word into a sort of question, and was looking at me for an answer.

One word was quite enough for the little fellow, and he went on, merrily:

"Well, and so he didn't want the other caterpillar to see the moth's wing, you know; so what must he do but t'y to carry it with all his left legs, and he t'ied to walk on the other set. Of course, he toppled over after that."

"After what?" I said, catching at the last word, for, to tell the truth, I hadn't been attending much.

"He toppled over," Bruno repeated, very gravely, "and if you ever saw a caterpillar topple over, you'd know it's a serious thing, and not sit g'inning like that—and I shan't tell you any more."

"Indeed and indeed, Bruno, I didn't mean to grin. See, I'm quite grave again now."

But Bruno only folded his arms and said, "Don't tell me. I see a little twinkle in one of your eyes—just like the moon."

"Am I like the moon, Bruno?" I asked.

"Your face is large and round like the moon," Bruno answered, looking at me thoughtfully. "It doesn't shine quite so bright—but it's cleaner."

I couldn't help smiling at this. "You know I wash my face, Bruno. The moon never does that."

"Oh, doesn't she though!" cried Bruno; and he leaned forward and added in a solemn whisper, "The moon's face gets dirtier and dirtier every night, till it's black all ac'oss. And then, when it's dirty all over—so—" (he passed his hand across his own rosy cheeks as he spoke) "then she washes it."

"And then it's all clean again, isn't it?"

"Not all in a moment," said Bruno. "What a deal of teaching you want! She washes it little by little—only she begins at the other edge."

By this time he was sitting quietly on the mouse, with his arms folded, and the weeding wasn't getting on a bit. So I was obliged to say:

"Work first and pleasure afterward; no more talking till that bed's finished."

After that we had a few minutes of silence, while I sorted out the pebbles, and amused myself with watching Bruno's plan of gardening. It was quite a new plan to me: he always measured each bed before he weeded it, as if he was afraid the weeding would make it shrink; and once, when it came out longer than he wished, he set to work to thump the mouse with his tiny fist, crying out, "There now! It's all 'ong again! Why don't you keep your tail st'aight when I tell you!"

"I'll tell you what I'll do," Bruno said in a half-whisper, as we worked: "I'll get you an invitation to the king's dinner-party. I know one of the head-waiters."

I couldn't help laughing at this idea. "Do the waiters invite the guests?" I asked.

"Oh, not to sit down!" Bruno hastily replied. "But to help, you know. You'd like that, wouldn't you? To hand about plates, and so on."

"Well, but that's not so nice as sitting at the table, is it?"

"Of course it isn't," Bruno said, in a tone as if he rather pitied my ignorance; "but if you're not even Sir Anything, you can't expect to be allowed to sit at the table, you know."

I said, as meekly as I could, that I didn't expect it, but it was the only way of going to a dinner-party that I really enjoyed. And Bruno tossed his head, and said, in a rather offended tone, that I might do as I pleased—there were many he knew that would give their ears to go.

"Have you ever been yourself, Bruno?"

"They invited me once last year," Bruno said, very gravely. "It was to wash up the soup-plates—no, the cheese-plates I mean—that was g'and enough. But the g'andest thing of all was, I fetched the Duke of Dandelion a glass of cider!"

"That was grand!" I said, biting my lip to keep myself from laughing.

"Wasn't it!" said Bruno, very earnestly. "You know it isn't every one that's had such an honor as that!"

This set me thinking of the various queer things we call "an honor" in this world, which, after all, haven't a bit more honor in them than what the dear little Bruno enjoyed (by the way, I hope you're beginning to like him a little, naughty as he was?) when he took the Duke of Dandelion a glass of cider.

I don't know how long I might have dreamed on in this way if Bruno hadn't suddenly roused me.

"Oh, come here quick!" he cried, in a state of the wildest excitement. "Catch hold of his other horn! I can't hold him more than a minute!"

He was struggling desperately with a great snail, clinging to one of its horns, and nearly breaking his poor little back in his efforts to drag it over a blade of grass.

I saw we should have no more gardening if I let this sort of thing go on, so I quietly took the snail away, and put it on a bank where he couldn't reach it. "We'll hunt it afterward, Bruno," I said, "if you really want to catch it. But what's the use of it when you've got it?"

"What's the use of a fox when you've got it?" said Bruno. "I know you big things hunt foxes."

I tried to think of some good reason why "big things" should hunt foxes, and he shouldn't hunt snails, but none came into my head: so I said at last, "Well, I suppose one's as good as the other. I'll go snail-hunting myself, some day."

"I should think you wouldn't be so silly," said Bruno, "as to go snail-hunting all by yourself. Why, you'd never get the snail along, if you hadn't somebody to hold on to his other horn!"

"Of course I sha'n't go alone," I said, quite gravely. "By the way, is that the best kind to hunt, or do you recommend the ones without shells?"

"Oh no! We never hunt the ones without shells," Bruno said, with a little shudder at the thought of it. "They're always so c'oss about it; and then, if you tumble over them, they're ever so sticky!"

By this time we had nearly finished the garden. I had fetched some violets, and Bruno was just helping me to put in the last, when he suddenly stopped and said, "I'm tired."

"Rest, then," I said; "I can go on without you."

Bruno needed no second invitation: he at once began arranging the mouse as a kind of sofa. "And I'll sing you a little song," he said as he rolled it about.

"Do," said I: "there's nothing I should like better."

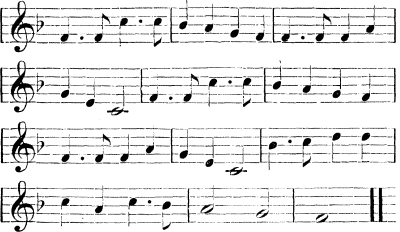

"Which song will you choose?" Bruno said, as he dragged the mouse into a place where he could get a good view of me. "'Ting, ting, ting,' is the nicest."

There was no resisting such a strong hint as this: however, I pretended to think about it for a moment, and then said, "Well, I like 'Ting, ting, ting,' best of all."

"That shows you're a good judge of music," Bruno said, with a pleased look. "How many bluebells would you like?" And he put his thumb into his mouth to help me to consider.

As there was only one bluebell within easy reach, I said very gravely that I thought one would do this time, and I picked it and gave it to him. Bruno ran his hand once or twice up and down the flowers,—like a musician trying an instrument,—producing a most delicious delicate tinkling as he did so. I had never heard flower-music before,—I don't think one can unless one's in the "eerie" state,—and I don't know quite how to give you an idea of what it was like, except by saying that it sounded like a peal of bells a thousand miles off.

When he had satisfied himself that the flowers were in tune, he seated himself on the mouse (he never seemed really comfortable anywhere else), and, looking up at me with a merry twinkle in his eyes, he began. By the way, the tune was rather a curious one, and you might like to try it for yourself, so here are the notes:

He sang the first four lines briskly and merrily, making the bluebells chime in time with the music; but the last two he sang quite slowly and gently, and merely waved the flowers backward and forward above his head. And when he had finished the first verse, he left off to explain.

"The name of our fairy king is Obberwon" (he meant Oberon, I believe), "and he lives over the lake—there—and now and then he comes in a little boat—and then we go and meet him—and then we sing this song, you know."

"And then you go and dine with him?" I said, mischievously.

"You shouldn't talk," Bruno hastily said; "it interrupts the song so."

I said I wouldn't do it again.

"I never talk myself when I'm singing," he went on, very gravely; "so you shouldn't either."

Then he tuned the bluebells once more, and sung:

"Hush, Bruno!" I interrupted, in a warning whisper. "She's coming!"

Bruno checked his song only just in time for Sylvie not to hear him; and then, catching sight of her as she slowly made her way through the long grass, he suddenly rushed out headlong at her like a little bull, shouting, "Look the other way! Look the other way!"

"Which way?" Sylvie asked, in rather a frightened tone, as she looked round in all directions to see where the danger could be.

"That way!" said Bruno, carefully turning her round with her face to the wood. "Now, walk backward—walk gently—don't be frightened; you sha'n't t'ip!"

But Sylvie did "t'ip," notwithstanding; in fact he led her, in his hurry, across so many little sticks and stones, that it was really a wonder the poor child could keep on her feet at all. But he was far too much excited to think of what he was doing.

I silently pointed out to Bruno the best place to lead her to, so as to get a view of the whole garden at once; it was a little rising ground, about the height of a potato; and, when they had mounted it, I drew back into the shade that Sylvie mightn't see me.

I heard Bruno cry out triumphantly, "Now you may look!" and then followed a great clapping of hands, but it was all done by Bruno himself. Sylvie was quite silent; she only stood and gazed with her hands clasped tightly together, and I was half afraid she didn't like it after all.

Bruno, too, was watching her anxiously, and when she jumped down from the mound, and began wandering up and down the little walks, he cautiously followed her about, evidently anxious that she should form her own opinion of it all, without any hint from him. And when at last she drew a long breath, and gave her verdict,—in a hurried whisper, and without the slightest regard to grammar,—"It's the loveliest thing as I never saw in all my life before!" the little fellow looked as well pleased as if it had been given by all the judges and juries in England put together.

"IT'S THE LOVELIEST THING AS I NEVER SAW IN ALL MY LIFE BEFORE!"

"And did you really do it all by yourself, Bruno?" said Sylvie. "And all for me?"

"I was helped a bit," Bruno began, with a merry little laugh at her surprise. "We've been at it all the afternoon; I thought you 'd like—" and here the poor little fellow's lip began to quiver, and all in a moment he burst out crying, and, running up to Sylvie, he flung his arms passionately round her neck, and hid his face on her shoulder.

There was a little quiver in Sylvie's voice too, as she whispered, "Why, what's the matter, darling?" and tried to lift up his head and kiss him.

But Bruno only clung to her, sobbing, and wouldn't be comforted till he had confessed all.

"I tried—to spoil your garden—first—but—I'll never—never——" and then came another burst of tears which drowned the rest of the sentence. At last he got out the words, "I liked—putting in the flowers—for you, Sylvie—and I never was so happy before," and the rosy little face came up at last to be kissed, all wet with tears as it was.

Sylvie was crying too by this time, and she said nothing but "Bruno dear!" and "I never was so happy before;" though why two children who had never been so happy before should both be crying was a great mystery to me.

I, too, felt very happy, but of course I didn't cry; "big things" never do, you know—we leave all that to the fairies. Only I think it must have been raining a little just then, for I found a drop or two on my cheeks.

After that they went through the whole garden again, flower by flower, as if it were a long sentence they were spelling out, with kisses for commas, and a great hug by way of a full-stop when they got to the end.

"Do you know, that was my river-edge, Sylvie?" Bruno began, looking solemnly at her.

Sylvie laughed merrily.

"What do you mean?" she said, and she pushed back her heavy brown hair with both hands, and looked at him with dancing eyes in which the big tear-drops were still glittering.

Bruno drew in a long breath, and made up his mouth for a great effort.

"I mean rev—enge," he said; "now you under'tand." And he looked so happy and proud at having said the word right at last that I quite envied him. I rather think Sylvie didn't "under'tand" at all; but she gave him a little kiss on each cheek, which seemed to do just as well.

So they wandered off lovingly together, in among the buttercups, each with an arm twined round the other, whispering and laughing as they went, and never so much as once looked back at poor me. Yes, once, just before I quite lost sight of them, Bruno half turned his head, and nodded me a saucy little good-bye over one shoulder. And that was all the thanks I got for my trouble.

I know you're sorry the story's come to an end—aren't you?—so I'll just tell you one thing more. The very last thing I saw of them was this: Sylvie was stooping down with her arms round Bruno's neck, and saying coaxingly in his ear, "Do you know, Bruno, I've quite forgotten that hard word; do say it once more. Come! Only this once, dear!"

But Bruno wouldn't try it again.

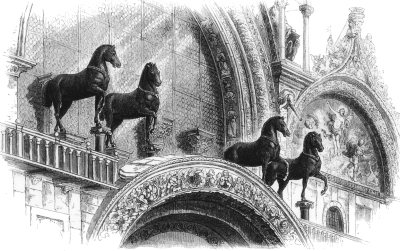

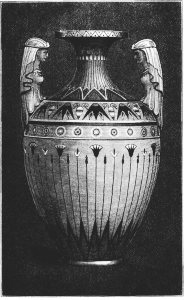

No doubt you all know something of Venice, that wonderful and fairy-like city which seems to rise up out of the sea; with its bridges and gondolas; its marble palaces coming down to the water's edge; its gay ladies and stately doges. What a magnificent pageant was that which took place every Ascension Day, when the doge and all his court sailed grandly out in the "Bucentaur," or state galley, with gay colors flying, to the tune of lively music, and went through the oft-repeated ceremony of dropping a ring into the Adriatic, in token of marriage between the sea and Venice! This was a custom instituted as far back as 1177. The Venetians having espoused the cause of the pope, Alexander III., against the emperor, Frederic Barbarossa, gained a great victory over the imperial fleet, and the pope, in grateful remembrance of the event, presented the doge with the ring symbolizing the subjection of the Adriatic to Venice.

But one of the most wonderful things about Venice is that, with the exception of those I intend to tell you about, there are no horses there. How charming it must be, you think, when you want to visit a friend, to run down the marble steps of some old palace, step into a gondola, and glide swiftly and noiselessly away, instead of jolting and rumbling along over the cobble-stones! And then to come back by moonlight, and hear the low plash of the oar in the water, and the distant voices of the boatmen singing some love-sick song,—oh, it's as good as a play!

Of course there are no carts in Venice; and the fish-man, the vegetable-man, the butcher, the baker, and the candlestick maker, all glide softly up in their boats to the kitchen door with their vendibles, and chaffer and haggle with the cook for half an hour, after the manner of market-men the world over.

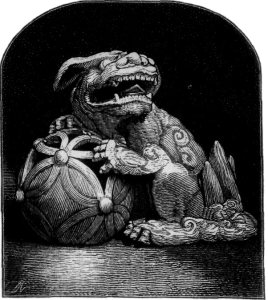

So you see the little black-eyed Venetian boys and girls gaze on the brazen horses in St. Mark's Square with as much wonder and curiosity as ours when we look upon a griffin or a unicorn.

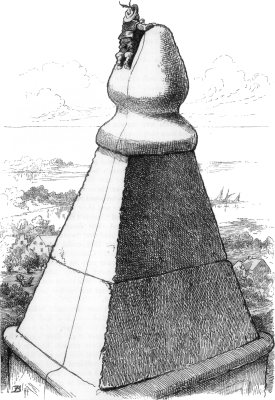

THE HORSES OF ST. MARK'S.

These horses—there are four of them—have quite a history of their own. They once formed part of a group made by a celebrated sculptor of antiquity, named Lysippus. He was of such acknowledged merit that he was one of the three included in the famous edict of Alexander, which gave to Apelles the sole right of painting his portrait, to Lysippus that of sculpturing his form in any style, and to Pyrgoteles that of engraving it upon precious stones.

Lysippus executed a group of twenty-five equestrian statues of the Macedonian horses that fell at the passage of the Granicus, and of this group the horses now at Venice formed a part. They were carried from Alexandria to Rome by Augustus, who placed them on his triumphal arch. Afterward Nero, Domitian and Trajan, successfully transferred them to arches of their own.

When Constantine removed the capital of the Roman empire to the ancient Byzantium, he sought to beautify it by all means in his power, and for this purpose he removed a great number of works of art from Rome to Constantinople, and among them these bronze horses of Lysippus.

In the early part of the thirteenth century the nobles of France and Germany, who were going on the fourth crusade, arrived at Venice and stipulated with the Venetians for means of transport to the Holy Land. But instead of proceeding to Jerusalem they were diverted from their original intention, and, under the leadership of the blind old doge, Dandolo, they captured the city of Constantinople. The fall of the city was followed by an almost total destruction of the works of art by which it had been adorned; for the Latins disgraced themselves by a more ruthless vandalism than that of the Vandals themselves.

But out of the wreck the four bronze horses were saved and carried in triumph to Venice, where they were placed over the central porch of St. Mark's Cathedral. There they stood until Napoleon Bonaparte in 1797 removed them with other trophies to Paris; but after his downfall they were restored, and, as Byron says in "Childe Harold":

Apropos of the last two lines I have quoted, I must tell you an incident of history.

During the middle ages, when so many of the Italian cities existed as independent republics, there was a great deal of rivalry between Genoa and Venice, the most important of them. Both were wealthy commercial cities; both strove for the supremacy of the sea, upon which much of their prosperity depended, and each strove to gain the advantage over the other. This led to many wars between them, when sometimes one would gain the upper hand, and sometimes the other. At length, in the year 1379, the Genoese defeated the Venetians in the battle of Pola, and then took Chiozza, which commanded, as one might say, the entrance to Venice. The Venetians, alarmed beyond measure, sent an embassy to the Genoese commander, Pietro Doria, agreeing to any terms whatever, imploring only that he would spare the city. They also sent the chief of the prisoners they had taken in the war in order to appease the fierce anger of the general. "Take back your captives, ye gentlemen of Venice," was the too confident reply of the haughty Doria; "we will release them and their companions. On God's faith, ye shall have no peace till we put a curb into the mouths of those wild horses of St. Mark's. Place but the reins once in our hands, and we shall know how to bridle them for the future."

Armed with the courage and energy which despair alone can give, the Venetians rallied for the defence of their city. Women and children joined in the preparations. All private feuds, jealousies and animosities were forgotten in the common danger. All were animated by the one feeling of implacable hatred of the Genoese. Pisani, an old commander, who had been unjustly imprisoned through the envy of his fellow-citizens, was released and put in command of the fleet. On coming out of his cell, he was surrounded by those who had injured him, who implored him to forget the injustice with which he had been treated. He partook of the sacrament with them in token of complete forgetfulness and forgiveness, and then proceeded against the enemy. The confidence of the republic had not been misplaced. His bravery, skill and foresight, together with the aid of another brave captain, Carl Zeno, saved the city, retook Chiozza, and completely humiliated the Genoese, who were now willing to sue for peace. So that, after all, Doria's angry menace was the means of saving the independence of the city, and the proud possession of the bronze horses of St. Mark's.

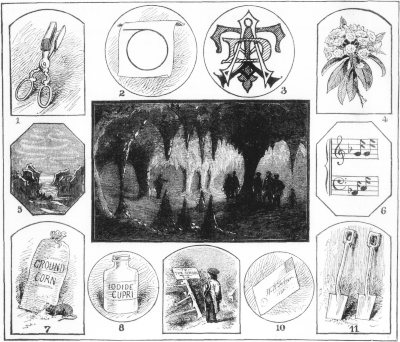

Ever since they had come home from the great Centennial at Philadelphia, the Peterkins had felt anxious to have "something." The little boys wanted to get up a "great Exposition," to show to the people of the place who had not been able to go to Philadelphia. But Mr. Peterkin thought it too great an effort, and it was given up.

There was, however, a new water-trough needed on the town-common, and the ladies of the place thought it ought to be something handsome,—something more than a common trough,—and they ought to work for it.

Elizabeth Eliza had heard at Philadelphia how much women had done, and she felt they ought to contribute to such a cause. She had an idea, but she would not speak of it at first, not until after she had written to the lady from Philadelphia. She had often thought, in many cases, if they had asked her advice first, they might have saved trouble.

Still, how could they ask advice before they themselves knew what they wanted? It was very easy to ask advice, but you must first know what to ask about. And again: Elizabeth Eliza felt you might have ideas, but you could not always put them together. There was this idea of the water-trough, and then this idea of getting some money for it. So she began with writing to the lady from Philadelphia. The little boys believed she spent enough for it in postage-stamps before it all came out.

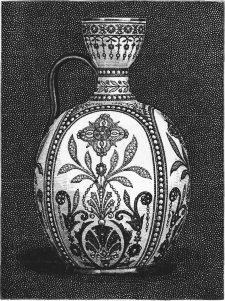

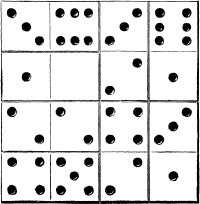

But it did come out at last that the Peterkins were to have some charades at their own house for the benefit of the needed water-trough,—tickets sold only to especial friends. Ann Maria Bromwich was to help act, because she could bring some old bonnets and gowns that had been worn by an aged aunt years ago, and which they had always kept. Elizabeth Eliza said that Solomon John would have to be a Turk, and they must borrow all the red things and Cashmere scarfs in the place. She knew people would be willing to lend things.

Agamemnon thought you ought to get in something about the Hindoos, they were such an odd people. Elizabeth Eliza said you must not have it too odd, or people would not understand it, and she did not want anything to frighten her mother. She had one word suggested by the lady from Philadelphia in her letters,—the one that had "Turk" in it,—but they ought to have two words.

"Oh yes," Ann Maria said, "you must have two words; if the people paid for their tickets, they would want to get their money's worth."

Solomon John thought you might have "Hindoos"; the little boys could color their faces brown to look like Hindoos. You could have the first scene an Irishman catching a hen, and then paying the water-taxes for "dues," and then have the little boys for Hindoos.

A great many other words were talked of, but nothing seemed to suit. There was a curtain, too, to be thought of, because the folding doors stuck when you tried to open and shut them. Agamemnon said the Pan-Elocutionists had a curtain they would probably lend John Osborne, and so it was decided to ask John Osborne to help.

If they had a curtain they ought to have a stage. Solomon John said he was sure he had boards and nails enough, and it would be easy to make a stage if John Osborne would help put it up.

All this talk was the day before the charades. In the midst of it Ann Maria went over for her old bonnets and dresses and umbrellas, and they spent the evening in trying on the various things,—such odd caps and remarkable bonnets! Solomon John said they ought to have plenty of bandboxes; if you only had bandboxes enough, a charade was sure to go off well; he had seen charades in Boston. Mrs. Peterkin said there were plenty in their attic, and the little boys brought down piles of them, and the back parlor was filled with costumes.

Ann Maria said she could bring over more things if she only knew what they were going to act. Elizabeth Eliza told her to bring anything she had,—it would all come of use.

The morning came, and the boards were collected for the stage. Agamemnon and Solomon John gave themselves to the work, and John Osborne helped zealously. He said the Pan-Elocutionists would lend a scene also. There was a great clatter of bandboxes, and piles of shawls in corners, and such a piece of work in getting up the curtain! In the midst of it, came in the little boys, shouting, "All the tickets are sold at ten cents each!"

"Seventy tickets sold!" exclaimed Agamemnon.

"Seven dollars for the water-trough!" said Elizabeth Eliza.

"And we do not know yet what we are going to act!" exclaimed Ann Maria.

But everybody's attention had to be given to the scene that was going up in the background, borrowed from the Pan-Elocutionists. It was magnificent, and represented a forest.

"Where are we going to put seventy people?" exclaimed Mrs. Peterkin, venturing, dismayed, into the heaps of shavings and boards and litter.

The little boys exclaimed that a large part of the audience consisted of boys, who would not take up much room. But how much clearing and sweeping and moving of chairs was necessary before all could be made ready! It was late, and some of the people had already come to secure good seats even before the actors had assembled.

"What are we going to act?" asked Ann Maria.

"I have been so torn with one thing and another," said Elizabeth Eliza, "I haven't had time to think!"

"Haven't you the word yet?" asked John Osborne, for the audience was flocking in, and the seats were filling up rapidly.

"I have got one word in my pocket," said Elizabeth Eliza, "in the letter from the lady from Philadelphia. She sent me the parts of the word. Solomon John is to be a Turk, but I don't yet understand the whole of the word."

"You don't know the word and the people are all here!" said John Osborne, impatiently.

"Elizabeth Eliza!" exclaimed Ann Maria, "Solomon John says I'm to be a Turkish slave, and I'll have to wear a veil. Do you know where the veils are? You know I brought them over last night."

"Elizabeth Eliza! Solomon John wants you to send him the large cashmere scarf," exclaimed one of the little boys, coming in. "Elizabeth Eliza! you must tell us what kind of faces to make up!" cried another of the boys.

And the audience were heard meanwhile taking their seats on the other side of the thin curtain.

"You sit in front, Mrs. Bromwich, you are a little hard of hearing; sit where you can hear."

"And let Julia Fitch come where she can see," said another voice.

"And we have not any words for them to hear or see!" exclaimed John Osborne behind the curtain.

"Oh, I wish we'd never determined to have charades!" exclaimed Elizabeth Eliza. "Can't we return the money!"

"They are all here; we must give them something!" said John Osborne, heroically.

"And Solomon John is almost dressed," reported Ann Maria, winding a veil around her head.

"Why don't we take Solomon John's word 'Hindoos' for the first?" said Agamemnon.

John Osborne agreed to go in the first, hunting the "hin," or anything, and one of the little boys took the part of the hen, with the help of a feather duster. The bell rang, and the first scene began.

It was a great success. John Osborne's Irish was perfect. Nobody guessed it, for the hen crowed by mistake; but it received great applause.

Mr. Peterkin came on in the second scene to receive the water-rates, and made a long speech on taxation. He was interrupted by Ann Maria as an old woman in a huge bonnet. She persisted in turning her back to the audience, and speaking so low nobody heard her; and Elizabeth Eliza, who appeared in a more remarkable bonnet, was so alarmed, she went directly back, saying she had forgotten something. But this was supposed to be the effect intended, and it was loudly cheered.

Then came a long delay, for the little boys brought out a number of their friends to be browned for Hindoos. Ann Maria played on the piano till the scene was ready. The curtain rose upon five brown boys done up in blankets and turbans.

"I am thankful that is over," said Elizabeth Eliza, "for now we can act my word. Only I don't myself know the whole."

"Never mind, let us act it," said John Osborne, "and the audience can guess the whole."

"The first syllable must be the letter P," said Elizabeth Eliza, "and we must have a school."

Agamemnon was master, and the little boys and their friends went on as scholars. All the boys talked and shouted at once, acting their idea of a school by flinging peanuts about, and scoffing at the master.

"They'll guess that to be 'row,'" said John Osborne in despair; "they'll never guess 'P'!"

The next scene was gorgeous. Solomon John, as a Turk, reclined on John Osborne's army-blanket. He had on a turban, and a long beard, and all the family shawls. Ann Maria and Elizabeth Eliza were brought in to him, veiled, by the little boys in their Hindoo costumes.

This was considered the great scene of the evening, though Elizabeth Eliza was sure she did not know what to do,—whether to kneel or sit down; she did not know whether Turkish women did sit down, and she could not help laughing whenever she looked at Solomon John. He, however, kept his solemnity. "I suppose I need not say much," he had said, "for I shall be the 'Turk who was dreaming of the hour.'" But he did order the little boys to bring sherbet, and when they brought it without ice, insisted they must have their heads cut off, and Ann Maria fainted, and the scene closed.

"What are we to do now?" asked John Osborne, warming up to the occasion.

"We must have an 'inn' scene," said Elizabeth Eliza, consulting her letter; "two inns if we can."

"We will have some travelers disgusted with one inn, and going to another," said John Osborne.

"Now is the time for the bandboxes," said Solomon John, who, since his Turk scene was over, could give his attention to the rest of the charade.

Elizabeth Eliza and Ann Maria went on as rival hostesses, trying to draw Solomon John, Agamemnon and John Osborne into their several inns. The little boys carried valises, hand-bags, umbrellas and bandboxes. Bandbox after bandbox appeared, and when Agamemnon sat down upon his, the applause was immense. At last the curtain fell.

"Now for the whole," said John Osborne, as he made his way off the stage over a heap of umbrellas.

"I can't think why the lady from Philadelphia did not send me the whole," said Elizabeth Eliza, musing over the letter.

"Listen, they are guessing," said John Osborne. "'D-ice-box.' I don't wonder they get it wrong."

"But we know it can't be that!" exclaimed Elizabeth Eliza, in agony. "How can we act the whole if we don't know it ourselves!"

"Oh, I see it!" said Ann Maria, clapping. "Get your whole family in for the last scene."

Mr. and Mrs. Peterkin were summoned to the stage, and formed the background, standing on stools; in front were Agamemnon and Solomon John, leaving room for Elizabeth Eliza between; a little in advance, and in front of all, half kneeling, were the little boys in their India rubber boots.

The audience rose to an exclamation of delight, "the Peterkins!"

It was not until this moment that Elizabeth Eliza guessed the whole.

"What a tableau!" exclaimed Mr. Bromwich; "the Peterkin family guessing their own charade."

The elm-tree avenue was all overgrown, the great gate was never unlocked, and the old house had been shut up for several years. Yet voices were heard about the place, the lilacs nodded over the high wall as if they said, "We could tell fine secrets if we chose," and the mullein outside the gate made haste to reach the keyhole that it might peep in and see what was going on.

If it had suddenly grown up like a magic bean-stalk, and looked in on a certain June day, it would have seen a droll but pleasant sight, for somebody evidently was going to have a party.

From the gate to the porch went a wide walk, paved with smooth slabs of dark stone, and bordered with the tall bushes which met overhead, making a green roof. All sorts of neglected flowers and wild weeds grew between their stems, covering the walls of this summer parlor with the prettiest tapestry. A board, propped on two blocks of wood, stood in the middle of the walk, covered with a little plaid shawl much the worse for wear, and on it a miniature tea service was set forth with great elegance. To be sure, the tea-pot had lost its spout, the cream-jug its handle, the sugar-bowl its cover, and the cups and plates were all more or less cracked or nicked; but polite persons would not take notice of these trifling deficiencies, and none but polite persons were invited to this party.

On either side of the porch was a seat, and here a somewhat remarkable sight would have been revealed to any inquisitive eye peering through the aforesaid key-hole. Upon the left-hand seat lay seven dolls, upon the right-hand seat lay six, and so varied were the expressions of their countenances, owing to fractures, dirt, age and other afflictions, that one would very naturally have thought this a doll's hospital, and these the patients waiting for their tea. This, however, would have been a sad mistake; for, if the wind had lifted the coverings laid over them, it would have disclosed the fact that all were in full dress, and merely reposing before the feast should begin.

There was another interesting feature of the scene which would have puzzled any but those well acquainted with the manners and customs of dolls. A fourteenth rag baby, with a china head, hung by her neck from the rusty knocker in the middle of the door. A sprig of white and one of purple lilac nodded over her, a dress of yellow calico, richly trimmed with red flannel scallops, shrouded her slender form, a garland of small flowers crowned her glossy curls, and a pair of blue boots touched toes in the friendliest, if not the most graceful, manner. An emotion of grief, as well as of surprise, might well have thrilled any youthful breast at such a spectacle, for why, oh! why, was this resplendent dolly hung up there to be stared at by thirteen of her kindred? Was she a criminal, the sight of whose execution threw them flat upon their backs in speechless horror? Or was she an idol, to be adored in that humble posture? Neither, my friends. She was blonde Belinda, set, or rather hung, aloft, in the place of honor, for this was her seventh birthday, and a superb ball was about to celebrate the great event.

"A RAG-BABY HUNG FROM THE RUSTY KNOCKER."

All were evidently awaiting a summons to the festive board, but such was the perfect breeding of these dolls that not a single eye out of the whole twenty-seven (Dutch Hans had lost one of the black beads from his worsted countenance) turned for a moment toward the table, or so much as winked, as they lay in decorous rows, gazing with mute admiration at Belinda. She, unable to repress the joy and pride which swelled her sawdust bosom till the seams gaped, gave an occasional bounce as the wind waved her yellow skirts or made the blue boots dance a sort of jig upon the door. Hanging was evidently not a painful operation, for she smiled contentedly, and looked as if the red ribbon around her neck was not uncomfortably tight; therefore, if slow suffocation suited her, who else had any right to complain? So a pleasing silence reigned, not even broken by a snore from Dinah, the top of whose turban alone was visible above the coverlet, or a cry from baby Jane, though her bare feet stuck out in a way that would have produced shrieks from a less well-trained infant.

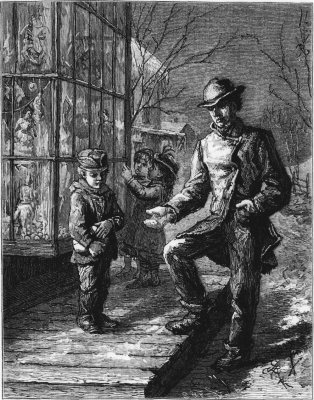

Presently voices were heard approaching, and through the arch which led to a side path came two little girls, one carrying a small pitcher, the other proudly bearing a basket covered with a napkin. They looked like twins, but were not—for Bab was a year older than Betty, though only an inch taller. Both had on brown calico frocks, much the worse for a week's wear, but clean pink pinafores, in honor of the occasion, made up for that, as well as the gray stockings and thick boots. Both had round rosy faces rather sunburnt, pug noses somewhat freckled, merry blue eyes, and braided tails of hair hanging down their backs like those of the dear little Kenwigses.

BAB AND BETTY ON THEIR WAY TO THE TEA-PARTY.

"Don't they look sweet?" cried Bab, gazing with maternal pride upon the left-hand row of dolls, who might appropriately have sung in chorus, "We are seven."

"Very nice; but my Belinda beats them all. I do think she is the splendidest child that ever was!" And Betty set down the basket to run and embrace the suspended darling, just then kicking up her heels with joyful abandon.

"The cake can be cooling while we fix the children. It does smell perfectly delicious!" said Bab, lifting the napkin to hang over the basket, fondly regarding the little round loaf that lay inside.

"Leave some smell for me!" commanded Betty, rushing back to get her fair share of the spicy fragrance.

The pug noses sniffed it up luxuriously, and the bright eyes feasted upon the loveliness of the cake, so brown and shiny, with a tipsy-looking B in pie-crust staggering down one side, instead of sitting properly atop.

"Ma let me put it on the very last minute, and it baked so hard I couldn't pick it off. We can give Belinda that piece, so it's just as well," observed Betty, taking the lead, as her child was queen of the revel.

"Let's set them round, so they can see too," proposed Bab, going, with a hop, skip and jump, to collect her young family.

Betty agreed, and for several minutes both were absorbed in seating their dolls about the table, for some of the dear things were so limp they wouldn't sit up, and others so stiff they wouldn't sit down, and all sorts of seats had to be contrived to suit the peculiarities of their spines. This arduous task accomplished, the fond mammas stepped back to enjoy the spectacle, which, I assure you, was an impressive one. Belinda sat with great dignity at the head, her hands genteelly holding a pink cambric pocket-handkerchief in her lap. Josephus, her cousin, took the foot, elegantly arrayed in a new suit of purple and green gingham, with his speaking countenance much obscured by a straw hat several sizes too large for him; while on either side sat guests of every size, complexion and costume, producing a very gay and varied effect, as all were dressed with a noble disregard of fashion.

"They will like to see us get tea. Did you forget the buns?" inquired Betty, anxiously.

"No; got them in my pocket." And Bab produced from that chaotic cupboard two rather stale and crumbly ones, saved from lunch for the fete. These were cut up and arranged in plates, forming a graceful circle around the cake, still in its basket.

"Ma couldn't spare much milk, so we must mix water with it. Strong tea isn't good for children, she says." And Bab contentedly surveyed the gill of skim-milk which was to satisfy the thirst of the company.

"While the tea draws and the cake cools let's sit down and rest; I'm so tired!" sighed Betty, dropping down on the door-step and stretching out the stout little legs which had been on the go all day; for Saturday had its tasks as well as its fun, and much business had preceded this unusual pleasure.

Bab went and sat beside her, looking idly down the walk toward the gate, where a fine cobweb shone in the afternoon sun.

"Ma says she is going over the house in a day or two, now it is warm and dry after the storm, and we may go with her. You know she wouldn't take us in the fall, 'cause we had whooping-cough and it was damp there. Now we shall see all the nice things; wont it be fun?" observed Bab, after a pause.

"Yes, indeed! Ma says there's lots of books in one room, and I can look at 'em while she goes round. May be I'll have time to read some, and then I can tell you," answered Betty, who dearly loved stories and seldom got any new ones.

"I'd rather see the old spinning-wheel up garret, and the big pictures, and the queer clothes in the blue chest. It makes me mad to have them all shut up there when we might have such fun with them. I'd just like to bang that old door down!" And Bab twisted round to give it a thump with her boots. "You needn't laugh; you know you 'd like it as much as me," she added, twisting back again, rather ashamed of her impatience.

"I didn't laugh."

"You did! Don't you suppose I know what laughing is?"

"I guess I know I didn't."

"You did laugh! How darst you tell such a fib?"

"If you say that again I'll take Belinda and go right home; then what will you do?"

"I'll eat up the cake."

"No, you wont! It's mine, ma said so, and you are only company, so you'd better behave or I wont have any party at all, so now."

This awful threat calmed Bab's anger at once, and she hastened to introduce a safer subject.

"Never mind; don't let's fight before the children. Do you know ma says she will let us play in the coach-house next time it rains, and keep the key if we want to."

"Oh, goody! that's because we told her how we found the little window under the woodbine, and didn't try to go in, though we might have just as easy as not," cried Betty, appeased at once, for after a ten years' acquaintance she had grown used to Bab's peppery temper.